This week’s Proust Questionnaire contestant is a new member of the Corresponding Society, Ryan Doyle May, who just read with us last week and has a chapbook forthcoming from our What Where series. Answers below!

Meet Ryan Doyle May

Ryan Doyle May's work has appeared in Almagre Literary Journal, Guilty As Charged, Bombay Gin, and Ganymede. His chapbook, The Anatomy of Gray is forthcoming on Corresponding Society Press. He has MFA in Creative Writing at The New School and blogs at thereckoningroom.blogspot.com.

Ryan Doyle May Answers the Proust Questionnaire

Your favorite virtue.

Humility.

Your favorite qualities in a man.

Weakness.

Your favorite qualities in a woman.

Violence.

Your chief characteristic.

Bangs.

What you appreciate the most in your friends.

Loyalty.

Your main fault.

Procrastination.

Your favorite occupation.

The business of words.

Your idea of happiness.

Depends on how much I have written.

Your idea of misery

Creative impotence

If not yourself, who would you be?

I have never been myself.

Where would you like to live?

In a pillow book

Your favorite prose authors.

Bhanu Kapil, Margaurite Duras, Milan Kundera, Anais Nin

Your favorite poets.

Anne Sexton, Federico Garcia Lorca, Akilah Oliver, Anne Carson

Your favorite heroes in fiction.

Odysseus, Humbert Humbert, The Little Prince

Your favorite heroines in fiction.

Ava, Anna Karina, Sabina (Nin’s Sabina)

Your favorite painters and composers.

Andrew Wyeth, Francis Bacon, Robert Mapplethorpe, Eric Satie

Your heroes in “real life.”

Bhanu Kapil

What characters in history do you most dislike?

Hitler and Dale Peck.

Your favorite names.

Symphony.

What do you hate the most?

Indifference.

What military event do you admire the most?

I wouldn’t call it admiration.

What reform do you admire the most?

Reform is another word for stagnation. Revolt!

The natural talent you’d like to be gifted with.

I would like the ability to switch gender at will.

How do you wish to die?

I wish to die like the sun.

What is your present state of mind?

Red.

For what fault do you have the most toleration?

Egotism.

Your favorite motto.

“Perhaps I am doomed to retrace my steps under the illusion that I am exploring, doomed to try and learn what I should simply recognize, learning a mere fraction of what I have forgotten.”

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Two Happenings

The following two events are not to miss:

The Corresponding Society Presents a Birthday Party

Saturday, March 27

7-9pm

at Unnameable Books

600 Vanderbilt Ave (at St. Marks), Brooklyn

This is a birthday party. There will be cake; the cake might be an inedible metaphor. There will be a triad of queer writers. There will be a confusion of forms, a conversation in problems, a bunch of shapes with sharp edges but lacking boundaries. The Corresponding Society presents a fun time in the basement of a bookstore, a queer party of documents on Lonely Christopher’s birthday, a parade of monsters and glamour galore. Let them eat the alphabet.

Featured Readers:

Marc Andreottola has been published in Lifted Brow, Ganymede, Killing the Buddha, 2010 Wilde Stories, K48, Dennis Cooper’s anthology of new writers, Userlands, and elsewhere. He had a play in the 2008 NY Fringe Festival that Time Out NY called “sick and bizarre”. He has an CDR of his electronic music being released by the Houston label, Disaro, under the name, Fostercare. He also does occult video art, which has been shown in Brooklyn, France and Minneapolis.

Ryan Doyle May's work has appeared in Almagre Literary Journal, Guilty As Charged, Bombay Gin, and Ganymede. His chapbook, The Anatomy of Gray is forthcoming on Corresponding Society Press. He has MFA in Creative Writing at The New School and blogs at thereckoningroom.blogspot.com.

Lonely Christopher is the birthday boy.

With! Master of ceremonies Rachel Levitsky (Under the Sun, Neighbor) and other birthday surprises!

The Institutionalized Theater Presents an Evening of Superstition and Intellect

3 New Plays! 3 Nights only!

The Jalopy Theater

315 Columbia Street

Brooklyn

"Reverie of the Succubus" by Jody Buchman

"Endymion Dreams the Moon" by Lonely Christopher

"Fingertips of the Vital Blackbirds: A Ballad" by Robert Snyderman et al.

March 28, 8pm

March 29, 7pm

March 30, 8pm

$5

Three new plays by the founding members of The Institutionalized Theater. The works share a commonality in the exploration of poetics, consciousness, superstition and intellect, but differ greatly in aesthetic and function.

The first, "Reverie of a Succubus," by Jody Buchman stars a castrated witch doctor. Passion, delirium and magic are confronted in this hallucinated poem. This play stars Jody Buchman as Pretty, and Lauren Buxten as the Succubus.

"Endymion Dreams the Moon" by Lonely Christopher is the second play. In this play some winsome teen poet insomniac (Andy Egelhoff) likes writing verse in the margin of wakefulness and dreams but lately can’t get a grasp on his surroundings as a pushy stranger (Simon Dooley) arrives memorializing his good looks and refusing to leave him alone. The stranger pronounces on matters of temporality, love, youth, and beauty, but might be a stalker obsessed with the confused kid. The truth threatens to emerge in unlikely places: a dream, outer space, and a hospital room in New Jersey.

Lisandre Whitty and Robert Snyderman wrote and will direct "Fingertips of the Vital Blackbirds: A Ballad" The Vital Blackbirds will be a drawing and a map of notes. Noisy souls within mute consciousness. Will take place within a traveler’s satchel. Will be the worn of the travel-worn satchel. Tales told from first-hand and second-hand experience. Will be a resistance to patience and to impatience. Will be North American. Will tell of a journey that did not end. The play features Actors/Musicians: Gabrielle Doyon-Hanson, Fareed Sajan, Chanelle Bergeron, Lisandre Whitty and Robert Snyderman

The Institutionalized Theater was founded in the year 2007 by Jody Buchman, Lonely Christopher, and Robert Snyderman. The concept behind the project was to provide a venue for young creative writers to explore a theatrical grammar developed from their emerging poetics and formal perspectives. The company was born at the Pratt Institute and operated turbulently under that academic rubric through several on-campus productions that became instant scandals and celebrations. Institutionalized programs have also appeared at the Bowery Poetry Club (including Today’s Vengeance by Robert Snyderman; Slump Boat Sway by A.E. Wilson; Retardo and Gay Play 1 by Lonely Christopher), the Ontological-Hysteric (Sleep Shit by Robert Snyderman), and other venues (I Am Happy and Gay Play 2 by Lonely Christopher). This evening of superstition and intellect marks the first time all three founding members have directed plays for the same event.

More info here.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Writing After Jameson

Mae Saslaw is a contributor to and friend of The Corresponding Society.

“An aesthetic of cognitive mapping—a pedagogical political culture which seeks to endow the individual subject with some new heightened sense of its place in the global system—will necessarily have to respect this now enormously complex representational dialectic and invent radically new forms in order to do it justice. This is not then, clearly, a call for a return to some older kind of machinery, some older and more transparent national space, or some more traditional and reassuring perspectival or mimetic enclave: the new political art (if it is possible at all) will have to hold to the truth of postmodernism, that is to say, to its fundamental object—the world space of multinational capital—at the same time at which it achieves a breakthrough to some as yet unimaginable new mode of representing this last, in which we may again begin to grasp our positioning as individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and struggle which is at present neutralized by our spacial as well as our social confusion. The political form of postmodernism, if there ever is any, will have as its vocation the invention and projection of a global cognitive mapping, on a social as well as a spatial scale.”

-Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism

What I love about Jameson’s writing is the way his logic carries and keeps momentum. For Jameson, every argument deserves space to match its complexity; it is not worthwhile to begin an exploration, discover that it takes you someplace mired and unpleasant, and then back out of the fight. The paragraph quoted above could not abide any part of it replaced with ellipses, and I regret not having the patience nor real estate to post a full two pages of his text. That said, this paragraph describes a compelling challenge, and it’s one that I have decided to take on. I’m currently in the very (very) early stages of my first novel after writing short fiction for several years. As I start the project, I’m taking as much time as I need to think about what I’m doing and why, less in the sense of plot and more in the sense of politics. Writing after Jameson requires at least two objectives:

1)Regarding content, of course I must produce something that answers his questions: Is the new political art possible? And, how does one achieve a “breakthrough” beyond postmodernism without resorting to futile hybridization or, worst of all, pastiche?

2)Aesthetically, it is not an option to be anything other than exhaustive. We have seen before what exhaustive fiction looks like—and it can be incredibly beautiful in the right hands—but what do I mean by “exhaustive”? The purpose of describing, to the last, every chink in the wall is a transparent one; the critical reader immediately recognizes the familiar tack and takes the cue to start reading for line work and watching out for the buried, devastating clauses. But what I am talking about is something else. The details are allowed to get exhausted, drawn out, perhaps boring at times, but what is vital is that the story itself, its characters, leave out nothing. This is a fine line. The added difficulty here is to stay clear and concise at the same time. Perhaps the breakthrough we seek has something to do with an abandonment of writerly distance.

But the goals themselves are not yet clear. It may be obvious that the duty of a certain kind of writer is to be ambitious beyond one’s influences, to attempt a dreadful and (I imagine) totally unsatisfying form of transcendence in which one kills one’s heroes and teachers. I don’t believe that is the best approach, and it is not entirely mine. My own duty, as I see it, is to answer for my particular historical moment, to bring to light its products and lay bare its every intricacy. (I’ve been thinking a lot about generational issues, how one generation unfailingly criticizes its successors for their ignorance, their lack of taste, etc. Perhaps a side effect of this age-old social phenomenon is that it fuels the art of the so-called ignorant, who, for their own self-centered psychological reasons, must prove their parents wrong. I mean, duh?) That said, Jameson’s articulations of exactly what my particular historical moment entails and implies about my country’s chronic amnesia and about our cultural future provide a compelling set of questions that can only be answered in art. Criticism has great potential, and I practice it just as much as fiction, but at a certain point, someone must make something to be criticized. Perhaps this is the breakthrough, the direction in which art must go.

It’s almost easier to think of beginning a novel in the shadow of theory, as opposed to the shadow of my favorite authors. It’s easier because I don’t have to worry as much about imitating voice, about coming off as derivative, about “paling in comparison” if that means anything. It’s harder because the framework is far boggier: I don’t know what Jameson wants in a protagonist, or a plot line, or how heavy-handed he wants his politics. I know that I don’t want to write science fiction for my own personal, admittedly snobbish reasons, though most non-writers I talk to express some confusion as to why I don’t write science fiction (to which I have been known to take vocal offense). The last question is the hardest to answer: Jameson points out, time and again, that postmodern art fails (and this is, sometimes, one if its defining characteristics) when it becomes somehow politically apolitical, meaning that the argument we see on the surface goes no further, addresses no problems beyond itself. This is the “tampon in the teacup” category of artwork, which so many people think about first when they consider art today, and which us intellectual wankers complain about because such bad art ruins our reputation. (What we deserve to acknowledge at such times is that we are, on some level, concerned for our reputation; we long for an aesthetic universality that a few artists actively work against, and perhaps we deserve to be commended for that. Of course, who would care enough to commend us? Poor us.) I recognize immediately artwork from the above category, which may be called political art for the sake of political art, as opposed to art for the sake of politics. Who among us (I’m still talking about intellectual wankers) didn’t get aroused—perhaps even physically—the first time we heard the Godard bit about “The point was not to make political films, but to make films politically”?

Writers today simply don’t get to make books politically, at least not in the sense Godard meant. For Godard, the political film was one that explicated its means of production, that worked against Hollywood glamor, that exposed Hollywood fantasy for its expensive and deceptive escapism. As for myself, I have spent the past several years considering the ways in which means of production and distribution of fiction intersect with its political goals, but I have not yet understood what it means to write politically. It is important to acknowledge the origins and presentation of a work of fiction—who brought it to the public and why—especially given the recent state of the publishing industry and the work that has been done by so many to circumvent the challenges of publishing new and challenging works to a wide audience. Ultimately, though, we are all going to sit at our keyboards and write, and the political difference between writing a novel in a public library and on one’s own expensive laptop does not quite compare to what Godard was after with political film. In other words, fiction is not capable of exposing its material means of production in the same ways. So, if I wish to be a political writer, then the fiction itself must contain its own politics. This is the problem.

If Jameson has taught me anything so far (disclosure: I have not yet finished his book), it’s that the problem must be allowed its space to breathe, to mutate and grow branches, to loom overwhelmingly. He acknowledges the potential for critical theory to drive its practitioners to dead ends, namely in his description of Adorno’s ultimate “winner loses” paradox, in which he who comprehends the problem must also comprehend the fact that it is hopelessly unsolvable. (An analogue in common adage: “If you’re worried, it’s already too late.”) But what would it look like to consider, and to attempt to overcome, such a paradox in fiction?

“An aesthetic of cognitive mapping—a pedagogical political culture which seeks to endow the individual subject with some new heightened sense of its place in the global system—will necessarily have to respect this now enormously complex representational dialectic and invent radically new forms in order to do it justice. This is not then, clearly, a call for a return to some older kind of machinery, some older and more transparent national space, or some more traditional and reassuring perspectival or mimetic enclave: the new political art (if it is possible at all) will have to hold to the truth of postmodernism, that is to say, to its fundamental object—the world space of multinational capital—at the same time at which it achieves a breakthrough to some as yet unimaginable new mode of representing this last, in which we may again begin to grasp our positioning as individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and struggle which is at present neutralized by our spacial as well as our social confusion. The political form of postmodernism, if there ever is any, will have as its vocation the invention and projection of a global cognitive mapping, on a social as well as a spatial scale.”

-Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism

What I love about Jameson’s writing is the way his logic carries and keeps momentum. For Jameson, every argument deserves space to match its complexity; it is not worthwhile to begin an exploration, discover that it takes you someplace mired and unpleasant, and then back out of the fight. The paragraph quoted above could not abide any part of it replaced with ellipses, and I regret not having the patience nor real estate to post a full two pages of his text. That said, this paragraph describes a compelling challenge, and it’s one that I have decided to take on. I’m currently in the very (very) early stages of my first novel after writing short fiction for several years. As I start the project, I’m taking as much time as I need to think about what I’m doing and why, less in the sense of plot and more in the sense of politics. Writing after Jameson requires at least two objectives:

1)Regarding content, of course I must produce something that answers his questions: Is the new political art possible? And, how does one achieve a “breakthrough” beyond postmodernism without resorting to futile hybridization or, worst of all, pastiche?

2)Aesthetically, it is not an option to be anything other than exhaustive. We have seen before what exhaustive fiction looks like—and it can be incredibly beautiful in the right hands—but what do I mean by “exhaustive”? The purpose of describing, to the last, every chink in the wall is a transparent one; the critical reader immediately recognizes the familiar tack and takes the cue to start reading for line work and watching out for the buried, devastating clauses. But what I am talking about is something else. The details are allowed to get exhausted, drawn out, perhaps boring at times, but what is vital is that the story itself, its characters, leave out nothing. This is a fine line. The added difficulty here is to stay clear and concise at the same time. Perhaps the breakthrough we seek has something to do with an abandonment of writerly distance.

But the goals themselves are not yet clear. It may be obvious that the duty of a certain kind of writer is to be ambitious beyond one’s influences, to attempt a dreadful and (I imagine) totally unsatisfying form of transcendence in which one kills one’s heroes and teachers. I don’t believe that is the best approach, and it is not entirely mine. My own duty, as I see it, is to answer for my particular historical moment, to bring to light its products and lay bare its every intricacy. (I’ve been thinking a lot about generational issues, how one generation unfailingly criticizes its successors for their ignorance, their lack of taste, etc. Perhaps a side effect of this age-old social phenomenon is that it fuels the art of the so-called ignorant, who, for their own self-centered psychological reasons, must prove their parents wrong. I mean, duh?) That said, Jameson’s articulations of exactly what my particular historical moment entails and implies about my country’s chronic amnesia and about our cultural future provide a compelling set of questions that can only be answered in art. Criticism has great potential, and I practice it just as much as fiction, but at a certain point, someone must make something to be criticized. Perhaps this is the breakthrough, the direction in which art must go.

It’s almost easier to think of beginning a novel in the shadow of theory, as opposed to the shadow of my favorite authors. It’s easier because I don’t have to worry as much about imitating voice, about coming off as derivative, about “paling in comparison” if that means anything. It’s harder because the framework is far boggier: I don’t know what Jameson wants in a protagonist, or a plot line, or how heavy-handed he wants his politics. I know that I don’t want to write science fiction for my own personal, admittedly snobbish reasons, though most non-writers I talk to express some confusion as to why I don’t write science fiction (to which I have been known to take vocal offense). The last question is the hardest to answer: Jameson points out, time and again, that postmodern art fails (and this is, sometimes, one if its defining characteristics) when it becomes somehow politically apolitical, meaning that the argument we see on the surface goes no further, addresses no problems beyond itself. This is the “tampon in the teacup” category of artwork, which so many people think about first when they consider art today, and which us intellectual wankers complain about because such bad art ruins our reputation. (What we deserve to acknowledge at such times is that we are, on some level, concerned for our reputation; we long for an aesthetic universality that a few artists actively work against, and perhaps we deserve to be commended for that. Of course, who would care enough to commend us? Poor us.) I recognize immediately artwork from the above category, which may be called political art for the sake of political art, as opposed to art for the sake of politics. Who among us (I’m still talking about intellectual wankers) didn’t get aroused—perhaps even physically—the first time we heard the Godard bit about “The point was not to make political films, but to make films politically”?

Writers today simply don’t get to make books politically, at least not in the sense Godard meant. For Godard, the political film was one that explicated its means of production, that worked against Hollywood glamor, that exposed Hollywood fantasy for its expensive and deceptive escapism. As for myself, I have spent the past several years considering the ways in which means of production and distribution of fiction intersect with its political goals, but I have not yet understood what it means to write politically. It is important to acknowledge the origins and presentation of a work of fiction—who brought it to the public and why—especially given the recent state of the publishing industry and the work that has been done by so many to circumvent the challenges of publishing new and challenging works to a wide audience. Ultimately, though, we are all going to sit at our keyboards and write, and the political difference between writing a novel in a public library and on one’s own expensive laptop does not quite compare to what Godard was after with political film. In other words, fiction is not capable of exposing its material means of production in the same ways. So, if I wish to be a political writer, then the fiction itself must contain its own politics. This is the problem.

If Jameson has taught me anything so far (disclosure: I have not yet finished his book), it’s that the problem must be allowed its space to breathe, to mutate and grow branches, to loom overwhelmingly. He acknowledges the potential for critical theory to drive its practitioners to dead ends, namely in his description of Adorno’s ultimate “winner loses” paradox, in which he who comprehends the problem must also comprehend the fact that it is hopelessly unsolvable. (An analogue in common adage: “If you’re worried, it’s already too late.”) But what would it look like to consider, and to attempt to overcome, such a paradox in fiction?

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Proust/Zultanski

This week’s installment of our ongoing, slightly modified, Proust Questionnaire project features poet Steven Zultanski. He is wonderful.

Introduction to Steven Zultanski

Steven Zultanski is the author of Pad (Make Now, 2010) and Cop Kisser (BookThug, forthcoming 2010). He edits President's Choice magazine, a Lil' Norton publication. You can watch his YouTube videos here.

Steven Zultanski Answers the Proust Questionnaire

Your favorite virtue.

Friendship.

Your favorite qualities in a man.

Genius.

Your favorite qualities in a woman.

Genius.

Your chief characteristic.

You tell me!

What you appreciate the most in your friends.

Wit, thought, solidarity with a common cause, the fact that they are brilliant and make brilliant things and/or otherwise engage the world in a brilliant way which changes it, the world, slightly but decidedly for the better, IMO.

Your main fault.

The tendency to hold an occasional petty grudge.

Your favorite occupation.

Teacher.

Your idea of happiness.

Working on a poem, and then eating a delicious meal with a friend, preferably with beer involved. Oh, and being in love is pretty great when it happens and isn’t terrible.

Your idea of misery.

The idea of ever returning to Buffalo.

If not yourself, who would you be?

Myself.

Where would you like to live?

NYC.

Your favorite prose authors.

Beckett, Marx, Lacan. (I’m in grad school).

Your favorite poets.

I unapologetically love my friends’ poetry more than I love anyone else’s poetry, and their work inspires me: Lawrence Giffin, Marie Buck, Brad Flis, Rob Fitterman, Kim Rosenfield, Patrick Lovelace, Eric Baus, Divya Victor, Kenneth Goldsmith, Vanessa Place, Chris Sylvester, many many more.

Your favorite heroes in fiction.

N/A

Your favorite heroines in fiction.

N/A

Your favorite painters and composers.

Painters: I don’t think about painting that much, but I like a lot of paintings very much.

Composers: I think about music more than I think about painting: Morton Feldman, Ilhan Mimaroglu, Scott Walker, Mrs. Miller, Chris Cooper / Angst Hase Pfeffer Nase, Autechre, Eliane Radigue, Kate Bush, François Bayle, Tony Conrad, Merzbow, many more.

Your heroes in “real life.”

N/A

Your favorite names.

Dr. X, Mr. X, Mrs. X, Ms. X, Señor X.

What do you hate the most?

Politically: Exploitation and imperialism. Culturally: Middlebrow and indie cultural products. Personally: The self-help-styled myth of individuality or autonomy. All these things are related, I suppose.

What military event do you admire the most?

N/A

What reform do you admire the most?

Killing this shitty health care bill and then passing a universal health care bill.

The natural talent you’d like to be gifted with.

Musical ability. Though maybe that’s not so much a natural talent.

How do you wish to die?

Old and before my companion has died and after I’ve created many things and worked hard.

What is your present state of mind?

Tired. Hopeful. Self-reflexive.

For what fault do you have the most toleration?

Rudeness when accompanied by an opinionated arrogance when accompanied by thought.

Your favorite motto.

Just do it.

Introduction to Steven Zultanski

Steven Zultanski is the author of Pad (Make Now, 2010) and Cop Kisser (BookThug, forthcoming 2010). He edits President's Choice magazine, a Lil' Norton publication. You can watch his YouTube videos here.

Steven Zultanski Answers the Proust Questionnaire

Your favorite virtue.

Friendship.

Your favorite qualities in a man.

Genius.

Your favorite qualities in a woman.

Genius.

Your chief characteristic.

You tell me!

What you appreciate the most in your friends.

Wit, thought, solidarity with a common cause, the fact that they are brilliant and make brilliant things and/or otherwise engage the world in a brilliant way which changes it, the world, slightly but decidedly for the better, IMO.

Your main fault.

The tendency to hold an occasional petty grudge.

Your favorite occupation.

Teacher.

Your idea of happiness.

Working on a poem, and then eating a delicious meal with a friend, preferably with beer involved. Oh, and being in love is pretty great when it happens and isn’t terrible.

Your idea of misery.

The idea of ever returning to Buffalo.

If not yourself, who would you be?

Myself.

Where would you like to live?

NYC.

Your favorite prose authors.

Beckett, Marx, Lacan. (I’m in grad school).

Your favorite poets.

I unapologetically love my friends’ poetry more than I love anyone else’s poetry, and their work inspires me: Lawrence Giffin, Marie Buck, Brad Flis, Rob Fitterman, Kim Rosenfield, Patrick Lovelace, Eric Baus, Divya Victor, Kenneth Goldsmith, Vanessa Place, Chris Sylvester, many many more.

Your favorite heroes in fiction.

N/A

Your favorite heroines in fiction.

N/A

Your favorite painters and composers.

Painters: I don’t think about painting that much, but I like a lot of paintings very much.

Composers: I think about music more than I think about painting: Morton Feldman, Ilhan Mimaroglu, Scott Walker, Mrs. Miller, Chris Cooper / Angst Hase Pfeffer Nase, Autechre, Eliane Radigue, Kate Bush, François Bayle, Tony Conrad, Merzbow, many more.

Your heroes in “real life.”

N/A

Your favorite names.

Dr. X, Mr. X, Mrs. X, Ms. X, Señor X.

What do you hate the most?

Politically: Exploitation and imperialism. Culturally: Middlebrow and indie cultural products. Personally: The self-help-styled myth of individuality or autonomy. All these things are related, I suppose.

What military event do you admire the most?

N/A

What reform do you admire the most?

Killing this shitty health care bill and then passing a universal health care bill.

The natural talent you’d like to be gifted with.

Musical ability. Though maybe that’s not so much a natural talent.

How do you wish to die?

Old and before my companion has died and after I’ve created many things and worked hard.

What is your present state of mind?

Tired. Hopeful. Self-reflexive.

For what fault do you have the most toleration?

Rudeness when accompanied by an opinionated arrogance when accompanied by thought.

Your favorite motto.

Just do it.

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Hooray!

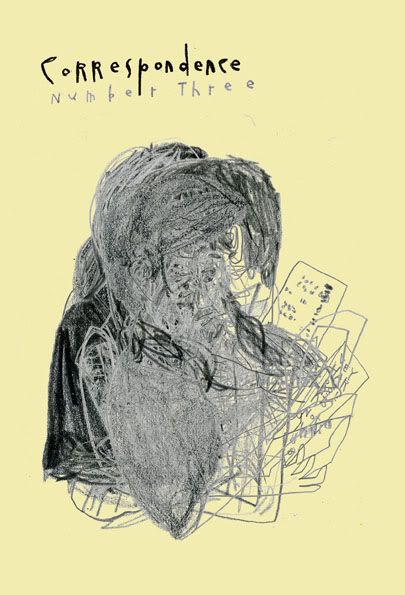

Brick is Red

Hey, thanks everybody who made it out to the KGB Bar on Wednesday for our issue three launch reading! We had a blast, as was expected. If you missed out (where were you!?), there’s some pictorial evidence of the event, in the form of a few snapshots, available on our website. Also, Justin Taylor was nice enough to provide a little write-up of the event on HTMLGIANT. Take it from Mr. Taylor: “You heard it here first, kids: these guys are onto something.” Remember, even if you didn’t catch the reading --- you can still bask in the splendor of Correspondence No. 3 by purchasing it (ten dollars, cheap!) from our Online Store! It’s out and awesome: more details re its contents available in this previous post.

No. 3 Takes San Francisco

And for any Bay Area residents who might be reading this --- take heed: Correspondence is set to hit California next week… with a West Coast launch reading at Adobe Books. Here’s the press release:

Please join us for an evening of ecstatic riddles, laughter, innuendo, and just plan kickass work by three outstanding writers, who celebrate the release of Correspondence #3, a new journal of poetry, prose, and critique hailing from Brooklyn.

Nona Caspers, levitational SF fictioneer and light of your evening, author of Little Book of Days and Heavier Than Air, will appear to neurally enchant. Lonely Christopher, enigma and co-editor of Correspondence, is in from New York for this one reading only – don’t miss his swanky and dangerous verbiage! Richard Loranger, unrepentant squeaky wheel and poeticist hunter, will swim in from Oakland to ignite a chunk of his life.

And once the wonder has worn off (if indeed it does), you can pick up your copy of Correspondence and browse the terrific selection at Adobe Books.

CORRESPONDENCE #3 RELEASE PARTY

a reading by

Nona Caspers

Lonely Christopher

and Richard Loranger

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

8 pm

free of charge

Adobe Bookshop

3166 – 16th Street

(between Valencia and Guererro)

San Francisco

PERFORMER BIOS

Nona Caspers is the author of LITTLE BOOK OF DAYS (2009) and Heavier Than Air (2007), which received the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction and was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has received a 2008 NEA Fellowship and an Iowa Review Fiction Award, among others. Her stories have appeared in Cimarron Review, The Iowa Review, Ontario Review, and Women on Women. She teaches Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Find out more at her website.

Lonely Christopher is a founding member of The Corresponding Society and an editor for its lit journal Correspondence. He is the author of the poetry volume Into (Seven CirclePress, with Robert Snyderman and Christopher Sweeney), the forthcoming short fiction collection The Mechanics of Homosexual Intercourse (Akashic, early 2011), and several chapbooks: Satan; Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land?; and Gay Plays. His plays have been directed internationally and published in Mandarin translation. His new plays Endymion Dreams the Moon and Pages from a Course in General Linguistics will be staged in New York City this March and April.

Richard Loranger is a writer, performer, visual artist, and all around squeaky wheel, currently residing in Oakland, CA. He is the author of Poems for Teeth (We Press, 2005), as well as The Orange Book and eight chapbooks, including Hello Poems and The Day Was Warm and Blue. Recent work can be found in Correspondence 1, 2 & 3 and CLWN WR 42& 45, and the Uphook Press anthology you say. say. He wants only a calm moment.

Hooray!

Sunday, March 7, 2010

Questions/Examples

Queer Paragraphs

questions and examples in poetics

by Lonely Christopher

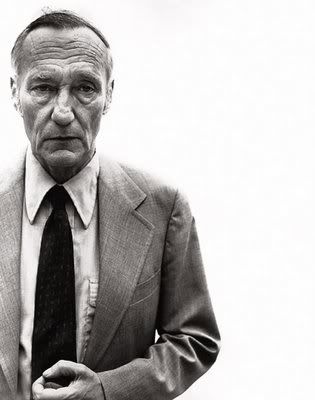

William S. Burroughs by Richard Avedon… No/Yes

The Ambiguities. What is a queer poetics? Alice Toklas does not answer. “In that case, what is the question?” That is queer poetics. This paradigm is architected on a foundational ambiguity. Example: Amy King writes herself out of taxonomy as introduction to her queer poetics. She begins, “I do not…” A negative impulse pushes the question farther and further: outside. This is an adventure in negotiating away from taxonomy. The engine of negative capability. Amy King writes about what doesn’t define her: “Such frames, these houses, do not hold, do not truly shelter nor constrain, do not even do good work as metaphor for the storehouse of my body, my language as system.” The sign vehicle crashes into a telephone pole. Ryan Doyle May promises: “We will burn definition’s home.” Queer poetics is a measurement of measurement’s failures, the unanswered question: a messy celebration of the unanswerable. Where do we put this? Gertrude Stein: “Next to vast which is which it is.” Is it? No/yes --- it is and isn’t.

A Thematic. Queer poetics doesn’t mean entirely in earnest, it’s an amorphous rubric, no incumbent constitutionality. That is, it is not shaped by a coherent/canonized value system that’s purposed ideologically against a heteronormative poetic tradition. A queer poetics isn’t implicitly correlative to any particular politics and/or politic responsibilities and/or praxis. It should exist outside the power structure that contains that discourse, but become accessible by readerly politicized positions. Example: a queer poetry is not the gay poetry. And yes it can be, but the latter has to solicit the former and only borrow it like a costume. That’s why there’s a lack of representative anthologies of queer writing: editors grasp out for queer and sculpt the material snatched from the far corners of definition into a shape conditioned by hegemonic discourses. This problem is recognized by CAConrad thus: “How queer was the poet?” The queerness isn’t in the poetry, the poetry’s in the queerness. And furthermore: “Queer poets are poets who need to create the best possible poems they have to offer, and need to do so without the policing of how many queer items appear in a poem to be considered queer. The fact that you are a poet who is queer is enough. The experience your body has carried into time will create the poem. And the experience of being queer WILL be in the poem, whether it's automatically recognizable or not.”

The Complications. Restatement: queer poetics is not predicated upon a culture; culture is differently articulated through the processes of a (descriptive) queer grammar. Amy King, here again, posits a behavior: “In its mercurial condition, queer poetry may throw a wrench in the cogs of the white male heterosexual default setting.” This, however, arrives with the caveat: “A queer poetry may offer a few common features [but] there is no single identifiable trait that enables the culture-at-large to recognize, absorb, contain, and imprison it.” Stein instructs us: the change of color likely, the difference prepared, and sugar is not a vegetable. Queerness haunts the machine, articulating differences. We don’t know what it means totally but we think it’s without totality. Stein: “Do you know by what means rockets signal pleasure pain and noise and union, do you know by what means a rock is freed when it is not held too tightly held in the hand.” The value generation of normative poetics functions like a statement with an empty subject: It is.. In this example, the verb is linguistically considered “avalent,” but that’s a misnomer insofar as the directness of the statement operates as the valent curtain over a surface of its essential problem (“it” also isn’t); a valence, in other words, is a length of decorative drapery attached to a frame in order to screen the structure or space beneath it. Queerness introduces existential arguments that complicate the conceptual valency of the definable/singular --- queerness pushes the structure centrifugally in other territories.

A Form. How do queer “values” form and operate? An opera: “He asked as if that made a difference.” Burroughs wanted to discover what was not human, instead of asking after definition, in his treatment of what we are and why we do what we do to each other. The monster tells the truth because of the difference, the difference makes it monstrous. The operational form of queerness works as difference, as a difference engine, processing values analytically, chewing up judgments. That’s an asking of questions as if that makes a difference. The grammar of a queer poetics is an anti-lesson in morphology. The site of an application of queer grammar becomes a living difference. When a queer poetics, in its liquidity, pours into an ideological shape --- the result doesn’t re-form queerness, it queers the form. Amy King writes: “A queer poetics is not only about what is but is equally about what is not. We live in relation to each other, regardless of our best efforts to divorce and secede. The human species is a community that communes even beyond its species. We do so violently, sometimes kindly and in multiple capacities.” The form isn’t divorced from the relationship --- the relationship as a question of differences. Photographer Richard Avedon’s motto: The No forces me into the Yes. “I have a white background. I have the person I’m interested in and what happens between us.” Queerness reads the naked surface of form, what’s underneath the drape of it is, and examples the structures that define by negative process. Andy Warhol isn’t dead.

The Distinctions. Bourdieu: “I believe it is possible to enter into the singularity of an object without renouncing the ambition of drawing out universal propositions.” Queer poetry is the rhizome lurking within the normative order. The monster attacking an institutional address, &c. The outlaw mode troubling the dominant definition: quietly infecting the postures of the cultural logic that states “it is” --- with problems, multiplicities of “it is this and it is not and/or this is not this this and/or it is this and this is not not this and/or it is not this not this and this is this and not it and/or this is it… not…” The value will explode and flower. Queerness hacks the cultural code with difference. “Social subjects, classified by their classifications, distinguish themselves by the distinctions they make[.]” Queer poetry happens in the negative space of the distinctions. Queer poetry is not verse by heterosexuals. Nor is it fundamentally verse by homosexuals, its chief practitioners. Its subject is subjectivity; its author is a performance artist and a scientist writing out emotional math in the theater of meaning. “There is no there there,” an absent voice rises. Amy King responds the we know “that there is no there there, there is only now and then now, there is no permanence, and that knowledge encourages the exploration of what now really is beyond the false fences of security, of a center, a normal, for higher dreams and greater privileges that can be shared between us, among us, in our constant becoming, however fleeting, however impossible […]” Queer poetry is questions and examples, is a problematic’s florescence. There: there is a question/problem floating in space, waiting to become what isn’t what is, waiting to grow into a black hole of others’ actualization[s]. “The result is that they know the difference between instead and instead and made and made and said and said. / The result is that they might be as very well two and as soon three and to be sure, four and which is why they might not be,” quoth Stein again. There is no queer history that’s not the history of disturbing our convenient and singular drapes. The anachronistic possibilities of queer poetics are hidden like land minds across our retrospection: ahistorical resonances waiting to blow up the surface area of meaning’s government. We attempt to write/inscribe queer poetry onto the ideological domain of a systemic totalization --- regardless of normative context, which we understand as a suppressive agent, we interrupt again and again the scripted conversation and hold up a dark funhouse mirror to institutionalized perspectives. A sonnet by Shakespeare is a queer threat if the reader makes the distinctions. The queer library hasn’t been written yet, happens everywhere, and is not going to be finished, ever.

A Love.

“I do love roses and carnations. / A mistake […] / I call it something religious. You mean beautiful. I do not know that […]” All of this is a neologism meaning and not meaning love; love becoming its other, poetry’s description[s] blurring, this the flow of argot pushing and shoving the way “it is” out of itself, this a version of how queerness means not finally but now: when we pull back the decorative drapery obscuring this subject, this essay, and this terminally unfinished sentence […]

The Sources. The Ambiguities: Gertrude Stein’s last conversation reconfigured; “The What Else of Queer Poetry” by Amy King (Text); The Anatomy of Gray by Ryan Doyle May; “Patriarchal Poetry” by Gertrude Stein. A Thematic: “What’s a Queer Poem?” by CAConrad (Text). The Complications: Ibid by Amy King; paraphrased from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein; “An Instant Answer” by Gertrude Stein; “Valence” definition paraphrased from the Oxford American Dictionary. A Form: “Four Saints in Three Acts” by Gertrude Stein; Ibid. by Amy King; Richard Avedon interview, source unidentified (found here). The Distinctions: “Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste” by Pierre Bourdieu; Ibid by Bourdieu; Everybody’s Autobiography by Gertrude Stein; Ibid by Amy King; “Patriarchal Poetry” (again) by Gertrude Stein. A Love: quote re-contextualized from “Lifting Belly” by Gertrude Stein. Further Reading: Amy King’s essay (online) “The What Else of Queer Poetry,” excerpted here generously and probably beyond recognized allowance, is an intelligent treatment of the liberatory indeterminacy of queer poetics qua general term (the above was fully inspired/provoked by her text); see also: “Patriarchal Poetry” by Gertrude Stein.

questions and examples in poetics

by Lonely Christopher

William S. Burroughs by Richard Avedon… No/Yes

The Ambiguities. What is a queer poetics? Alice Toklas does not answer. “In that case, what is the question?” That is queer poetics. This paradigm is architected on a foundational ambiguity. Example: Amy King writes herself out of taxonomy as introduction to her queer poetics. She begins, “I do not…” A negative impulse pushes the question farther and further: outside. This is an adventure in negotiating away from taxonomy. The engine of negative capability. Amy King writes about what doesn’t define her: “Such frames, these houses, do not hold, do not truly shelter nor constrain, do not even do good work as metaphor for the storehouse of my body, my language as system.” The sign vehicle crashes into a telephone pole. Ryan Doyle May promises: “We will burn definition’s home.” Queer poetics is a measurement of measurement’s failures, the unanswered question: a messy celebration of the unanswerable. Where do we put this? Gertrude Stein: “Next to vast which is which it is.” Is it? No/yes --- it is and isn’t.

A Thematic. Queer poetics doesn’t mean entirely in earnest, it’s an amorphous rubric, no incumbent constitutionality. That is, it is not shaped by a coherent/canonized value system that’s purposed ideologically against a heteronormative poetic tradition. A queer poetics isn’t implicitly correlative to any particular politics and/or politic responsibilities and/or praxis. It should exist outside the power structure that contains that discourse, but become accessible by readerly politicized positions. Example: a queer poetry is not the gay poetry. And yes it can be, but the latter has to solicit the former and only borrow it like a costume. That’s why there’s a lack of representative anthologies of queer writing: editors grasp out for queer and sculpt the material snatched from the far corners of definition into a shape conditioned by hegemonic discourses. This problem is recognized by CAConrad thus: “How queer was the poet?” The queerness isn’t in the poetry, the poetry’s in the queerness. And furthermore: “Queer poets are poets who need to create the best possible poems they have to offer, and need to do so without the policing of how many queer items appear in a poem to be considered queer. The fact that you are a poet who is queer is enough. The experience your body has carried into time will create the poem. And the experience of being queer WILL be in the poem, whether it's automatically recognizable or not.”

The Complications. Restatement: queer poetics is not predicated upon a culture; culture is differently articulated through the processes of a (descriptive) queer grammar. Amy King, here again, posits a behavior: “In its mercurial condition, queer poetry may throw a wrench in the cogs of the white male heterosexual default setting.” This, however, arrives with the caveat: “A queer poetry may offer a few common features [but] there is no single identifiable trait that enables the culture-at-large to recognize, absorb, contain, and imprison it.” Stein instructs us: the change of color likely, the difference prepared, and sugar is not a vegetable. Queerness haunts the machine, articulating differences. We don’t know what it means totally but we think it’s without totality. Stein: “Do you know by what means rockets signal pleasure pain and noise and union, do you know by what means a rock is freed when it is not held too tightly held in the hand.” The value generation of normative poetics functions like a statement with an empty subject: It is.. In this example, the verb is linguistically considered “avalent,” but that’s a misnomer insofar as the directness of the statement operates as the valent curtain over a surface of its essential problem (“it” also isn’t); a valence, in other words, is a length of decorative drapery attached to a frame in order to screen the structure or space beneath it. Queerness introduces existential arguments that complicate the conceptual valency of the definable/singular --- queerness pushes the structure centrifugally in other territories.

A Form. How do queer “values” form and operate? An opera: “He asked as if that made a difference.” Burroughs wanted to discover what was not human, instead of asking after definition, in his treatment of what we are and why we do what we do to each other. The monster tells the truth because of the difference, the difference makes it monstrous. The operational form of queerness works as difference, as a difference engine, processing values analytically, chewing up judgments. That’s an asking of questions as if that makes a difference. The grammar of a queer poetics is an anti-lesson in morphology. The site of an application of queer grammar becomes a living difference. When a queer poetics, in its liquidity, pours into an ideological shape --- the result doesn’t re-form queerness, it queers the form. Amy King writes: “A queer poetics is not only about what is but is equally about what is not. We live in relation to each other, regardless of our best efforts to divorce and secede. The human species is a community that communes even beyond its species. We do so violently, sometimes kindly and in multiple capacities.” The form isn’t divorced from the relationship --- the relationship as a question of differences. Photographer Richard Avedon’s motto: The No forces me into the Yes. “I have a white background. I have the person I’m interested in and what happens between us.” Queerness reads the naked surface of form, what’s underneath the drape of it is, and examples the structures that define by negative process. Andy Warhol isn’t dead.

The Distinctions. Bourdieu: “I believe it is possible to enter into the singularity of an object without renouncing the ambition of drawing out universal propositions.” Queer poetry is the rhizome lurking within the normative order. The monster attacking an institutional address, &c. The outlaw mode troubling the dominant definition: quietly infecting the postures of the cultural logic that states “it is” --- with problems, multiplicities of “it is this and it is not and/or this is not this this and/or it is this and this is not not this and/or it is not this not this and this is this and not it and/or this is it… not…” The value will explode and flower. Queerness hacks the cultural code with difference. “Social subjects, classified by their classifications, distinguish themselves by the distinctions they make[.]” Queer poetry happens in the negative space of the distinctions. Queer poetry is not verse by heterosexuals. Nor is it fundamentally verse by homosexuals, its chief practitioners. Its subject is subjectivity; its author is a performance artist and a scientist writing out emotional math in the theater of meaning. “There is no there there,” an absent voice rises. Amy King responds the we know “that there is no there there, there is only now and then now, there is no permanence, and that knowledge encourages the exploration of what now really is beyond the false fences of security, of a center, a normal, for higher dreams and greater privileges that can be shared between us, among us, in our constant becoming, however fleeting, however impossible […]” Queer poetry is questions and examples, is a problematic’s florescence. There: there is a question/problem floating in space, waiting to become what isn’t what is, waiting to grow into a black hole of others’ actualization[s]. “The result is that they know the difference between instead and instead and made and made and said and said. / The result is that they might be as very well two and as soon three and to be sure, four and which is why they might not be,” quoth Stein again. There is no queer history that’s not the history of disturbing our convenient and singular drapes. The anachronistic possibilities of queer poetics are hidden like land minds across our retrospection: ahistorical resonances waiting to blow up the surface area of meaning’s government. We attempt to write/inscribe queer poetry onto the ideological domain of a systemic totalization --- regardless of normative context, which we understand as a suppressive agent, we interrupt again and again the scripted conversation and hold up a dark funhouse mirror to institutionalized perspectives. A sonnet by Shakespeare is a queer threat if the reader makes the distinctions. The queer library hasn’t been written yet, happens everywhere, and is not going to be finished, ever.

A Love.

“I do love roses and carnations. / A mistake […] / I call it something religious. You mean beautiful. I do not know that […]” All of this is a neologism meaning and not meaning love; love becoming its other, poetry’s description[s] blurring, this the flow of argot pushing and shoving the way “it is” out of itself, this a version of how queerness means not finally but now: when we pull back the decorative drapery obscuring this subject, this essay, and this terminally unfinished sentence […]

The Sources. The Ambiguities: Gertrude Stein’s last conversation reconfigured; “The What Else of Queer Poetry” by Amy King (Text); The Anatomy of Gray by Ryan Doyle May; “Patriarchal Poetry” by Gertrude Stein. A Thematic: “What’s a Queer Poem?” by CAConrad (Text). The Complications: Ibid by Amy King; paraphrased from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein; “An Instant Answer” by Gertrude Stein; “Valence” definition paraphrased from the Oxford American Dictionary. A Form: “Four Saints in Three Acts” by Gertrude Stein; Ibid. by Amy King; Richard Avedon interview, source unidentified (found here). The Distinctions: “Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste” by Pierre Bourdieu; Ibid by Bourdieu; Everybody’s Autobiography by Gertrude Stein; Ibid by Amy King; “Patriarchal Poetry” (again) by Gertrude Stein. A Love: quote re-contextualized from “Lifting Belly” by Gertrude Stein. Further Reading: Amy King’s essay (online) “The What Else of Queer Poetry,” excerpted here generously and probably beyond recognized allowance, is an intelligent treatment of the liberatory indeterminacy of queer poetics qua general term (the above was fully inspired/provoked by her text); see also: “Patriarchal Poetry” by Gertrude Stein.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

KGB Launch No. 3

Adrian Shirk at the KGB Bar

Correspondence No. 3 will be released on March 10! To celebrate, please join us for our third launch reading at the KGB Bar!

Featured readers, contributors to issue three all, include:

Christian Hawkey

Sonia Farmer

A.E. Wilson

Jody Buchman

Ben Fama

& Adrian Shirk

with introductions by Lonely Christopher.

Bios and more information available on the KGB Website.

Copies of No. 3 will be available for a tidy discount, drinks will be strong, walls will be red, you will be expected!

The Corresponding Society at the KGB Bar

March 10, 7pm-9pm

85 East 4th St.

Manhattan, New York

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)