Yes, we have a box of copies of Correspondence No. 1 left, but it is the last box of copies. I think. This is worth mentioning for anyone who was worried that the journal had become unavailable. Your concern is appreciated but totally unwarranted. The journal is, for the time being, the lone item available through our Online Store; we also accept orders through the postal service (please send inquiries to our email address). This collection of new work by unfamiliar writers is, concisely, a book to be read after purchasing. More information re the contents here. It is shiny.

The holiday season is a terrible time for us all, I presume, and I could relate an anecdote about being stuck sixteen hours on a train just to get across New York State, if there was anything else to unfold other than sitting still and reading Wuthering Heights. As our calendar is about to end, sentimentalized remembrances of the quondam year grow ever inadvisable. I will taciturnly refrain from congratulating the editors of The Corresponding Society for realizing this project of ours, but cannot help but fleetingly making plain my anticipation for next annum, which will shortly see a new issue of Correspondence (possibly exciting enough to pose serious health threats to the literate) along with other projects and occasions. I must restate that issue No. 2 is looking very attractive. To fill the empty hours until that’s ready, please refer to the Author Catalog on our website, which is looking slightly tidier than usual tonight. Notably, the entry for contributing editor Adrian Shirk has been newly enriched with her poetry and fiction.

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

Friday, December 12, 2008

Dancing Skeleton Reading

Making Skeletons Dance is a reading series, co-hosted by Correspondence contributing editor Adrian Shirk, at Unnamable Books of Brooklyn. The general theme is young writers presenting work about family. Below are the pertinent details about the next event:

Venue: Unnamable Books

Location: 456 Bergen Street, Brooklyn

Date: Tuesday, December 16

Time: 8pm-9:30pm

Featured Readers: Robert Balkovich, Shannon Harrison, Lily Herman, Lonely Christopher, Sophie Johnson, Ian McKenzie, Adrian Shirk

Coincidentally, Unnamable is one of the few distinguished independent bookstores in Brooklyn that we’re aware of and they happen to stock the first issue of Correspondence.

Venue: Unnamable Books

Location: 456 Bergen Street, Brooklyn

Date: Tuesday, December 16

Time: 8pm-9:30pm

Featured Readers: Robert Balkovich, Shannon Harrison, Lily Herman, Lonely Christopher, Sophie Johnson, Ian McKenzie, Adrian Shirk

Coincidentally, Unnamable is one of the few distinguished independent bookstores in Brooklyn that we’re aware of and they happen to stock the first issue of Correspondence.

Sunday, December 7, 2008

What Is The Bad Quarto?

As The Institutionalized Theater continues to build our production of Hamlet, I continue to write notes and ideas on both the play and this project as a way to develop my directorial approach. The following is an essay I wrote in the summer (around the time we moved out of the research phase and toward production) as a way to clarify textual matters. I was frequently asked what my “take” on Hamlet was --- my first answer was that we’re doing The Bad Quarto, which usually prompted a second question re what that meant. I wrote an essay focused on the textual complexities of Hamlet so I wouldn’t have to repeat my explanation awkwardly every time the question arose. I was going to use this essay in the show’s programme, but I think I’ve decided it’s too detailed for that purpose. Here it is:

A Document in Variance

by Lonely Christopher

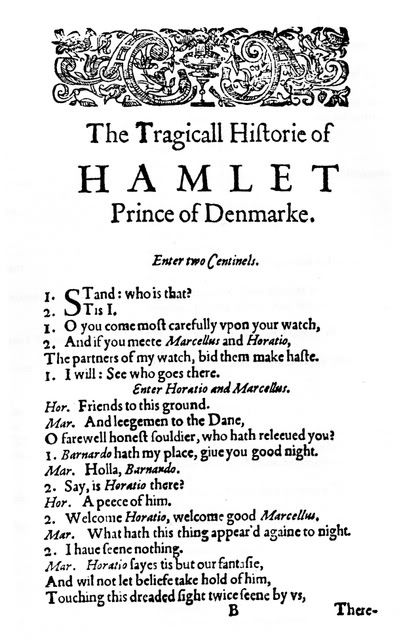

Works titled The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark were printed in different editions in the form of the quarto, comparable to a paperback, and the folio, often not dissimilar from thicker books of Shakespeare’s collected plays, most notably from 1603 to 1623; of all the extant texts three primary variants are remarkably distinguished: the First Quarto, the Second Quarto, and the First Folio. All three are accredited to Shakespeare, and insist upon legitimacy, but the disparities amongst them are so profound that it’s impossible to conceive of one cohesive and uncomplicated text representative of the impregnable, quintessential Hamlet. Hamlet is plural; it is a congregation of sources, manuscripts, editorial influences, and cultural perspectives. The Second Quarto (1605), which in content comfortably resembles the popular understanding of a “definitive” Hamlet, most likely derives from an authorial manuscript (foul papers). The especially complicated late Folio edition (1623) probably originates from a different source; in content it is seven percent unique, although ten percent of the Second Quarto’s dialog is absent from it. The First Quarto (1603), which we are using as a script for this production, is the most radically different and is seventy-nine percent shorter than the Second Quarto. The sources for Shakespeare’s Hamlet include anterior material such as a Nordic tale recorded in Latin circa 1200 CE by Saxo Grammaticus --- maybe by way of Francois de Belleforest’s Histoires Tragique --- aspects of Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, and the indefinable lost Ur-Hamlet of which little is known besides it must have existed (though it is posited by some that Kyd was the likely author). In those preceding works the broad outlines of our Hamlet are discernable --- though the blunt tropes of storytelling have yet to be rendered poetically ambiguous and complex by Shakespeare. The extensive accumulations of pertinent data are manipulated by editors until a recognizable Hamlet is wrought from heterogeneous texts. In the introduction to Arden’s new two-volume Hamlet, Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor summarize the ways in which the data can be presented for a general readership: “1. A photographic, or diplomatic, facsimile of a particular copy of a particular printed book [...]; 2. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of such a copy of Hamlet; 3. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of an ‘ideal’ [...] printed edition of a text [...]; 4. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of the reconstructed text of a lost manuscript assumed to lie behind a printed edition [...]; 5. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of a play (e.g. Shakespeare’s Hamlet).” A common production title Hamlet uses an idealized conflation of the Second Quarto and Folio; abridging it to a standard play length by excising dialog, scenes, and whole plot threads. The First Quarto constitutes the initial appearance in print of a play --- accredited to William Shakespeare --- titled The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, but what it is exactly is unconcluded. It entered the discourse of textual scholarship in 1823 when it was “discovered,” but a satisfactory explanation of its existence has never been reached. An early popular theory was that it is an altogether different play beside the other Hamlets attributed to Shakespeare --- an adaptation of another source text entirely. The story is more similar in minutiae to the Second Quarto than the Nordic tale, but certain names and aspects of narrative, not to mention dialog, are drastically unlike the canonized idea of Hamlet. Another mostly discounted theory is that the First Quarto represents an embarrassing first draft of what would eventually be crafted into Shakespeare’s “true” Hamlet --- or that it’s even the Ur-Hamlet itself. The fashionable theory, which has given rise to the accusation that the text is a bad quarto reflecting poor authorial fidelity, is that this version of the play is a memorial reconstruction. An actor (most likely he who played Marcellus and Voltemar judging by how closely his lines resemble the dialog of the other texts) wrote down what he remembered of the play and sold it to be printed first for his own gain. Thus the consequent Second Quarto is understood as a correction and usurpation of the initial edition; an effort that presumably reflects much more authorial fidelity. It is surprising to a modern reader how unstable all of the extant material is. For example, in the Second Quarto Hamlet is considered by others a youthful student until his age is remarkably revealed to be thirty in the last act, whereas the Bad Quarto features a reasonably teenaged Hamlet. Additionally, though the title Claudius is traditionally given to the character of the King it is doubtful that any conception of Shakespeare as a singular and historical author ever thought of the King with that name. Claudius is only named as such once at the beginning of the Second Quarto and the Folio and thereafter only referenced by his position; in the Bad Quarto he is never given a name at all. When one remembers that, in the Second Quarto, eventually an attendant mentions to the King a character named Claudio, the practice of calling the King Claudius seems more like an editorial imposition based on a printer’s quirk than the reflection of one definitive play. In the Bad Quarto many of the names are what might generally be considered “nonstandard.” Our Queen Gertred, Ofelia and her father Corambis, and Montano all suggest a Hamlet as the Shakespearean manifestation of antecedent stories of Hamnet, or Hamblet, or Amleth, or Amlodi. While the names Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are, rendered thus, widely recognizable they actually represent editorially systematized interpretations --- whereas in the three major versions of the play those specific names vary significantly even within each individual text in a way resulting from and illustrating the non-codified spelling of Elizabethan drama that is almost always modernized in print. In the Bad Quarto the dialog is abbreviated and less poetic --- scenes are shuffled, revised in another context, abridged, and deleted withal. Scene fourteen, in which Horatio clandestinely plots with the Queen, is notorious because it is found in no other version. In the Bad Quarto, opportunities to confront the play’s textuality are significant and unique. Threadbare edges of the material present interpretive challenges that must be met with ardent conceptualism. After I confronted the badness of the Bad Quarto, it was given out that this misfit Hamlet, while unpopular and estranged, seems superlative in is freakishness. Hamlet refuses to cohere into something neatly definitional or a successful “organic whole” expressing an “objective correlative” --- through the lens of postmodernity the “real figure” of the greatest writer ever (the author of humanity according to Bloom) seems untranslatable; ergo I posit that we can now say Shakespeare are authors. I think through that statement much more available surface area of the work is discoverable. As Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor wrote in the introduction to the new Arden Hamlet, “If by ‘Hamlet’ we mean a public representation of a ‘Hamlet’ narrative --- that is, a story involving a character called Hamlet who has some continuity of identity with the Amlodi figure of Nordic myth --- then these three texts are just three ‘expressions’ of Hamlet out of the infinite number of Hamlets which have or could have come into existence.” The textual and narrative multiplicity of data that are available to an interpreter can enable a reaching toward the Shakespearean infinite space.

A Document in Variance

by Lonely Christopher

Works titled The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark were printed in different editions in the form of the quarto, comparable to a paperback, and the folio, often not dissimilar from thicker books of Shakespeare’s collected plays, most notably from 1603 to 1623; of all the extant texts three primary variants are remarkably distinguished: the First Quarto, the Second Quarto, and the First Folio. All three are accredited to Shakespeare, and insist upon legitimacy, but the disparities amongst them are so profound that it’s impossible to conceive of one cohesive and uncomplicated text representative of the impregnable, quintessential Hamlet. Hamlet is plural; it is a congregation of sources, manuscripts, editorial influences, and cultural perspectives. The Second Quarto (1605), which in content comfortably resembles the popular understanding of a “definitive” Hamlet, most likely derives from an authorial manuscript (foul papers). The especially complicated late Folio edition (1623) probably originates from a different source; in content it is seven percent unique, although ten percent of the Second Quarto’s dialog is absent from it. The First Quarto (1603), which we are using as a script for this production, is the most radically different and is seventy-nine percent shorter than the Second Quarto. The sources for Shakespeare’s Hamlet include anterior material such as a Nordic tale recorded in Latin circa 1200 CE by Saxo Grammaticus --- maybe by way of Francois de Belleforest’s Histoires Tragique --- aspects of Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, and the indefinable lost Ur-Hamlet of which little is known besides it must have existed (though it is posited by some that Kyd was the likely author). In those preceding works the broad outlines of our Hamlet are discernable --- though the blunt tropes of storytelling have yet to be rendered poetically ambiguous and complex by Shakespeare. The extensive accumulations of pertinent data are manipulated by editors until a recognizable Hamlet is wrought from heterogeneous texts. In the introduction to Arden’s new two-volume Hamlet, Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor summarize the ways in which the data can be presented for a general readership: “1. A photographic, or diplomatic, facsimile of a particular copy of a particular printed book [...]; 2. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of such a copy of Hamlet; 3. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of an ‘ideal’ [...] printed edition of a text [...]; 4. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of the reconstructed text of a lost manuscript assumed to lie behind a printed edition [...]; 5. An old-spelling, or modernized, edition of a play (e.g. Shakespeare’s Hamlet).” A common production title Hamlet uses an idealized conflation of the Second Quarto and Folio; abridging it to a standard play length by excising dialog, scenes, and whole plot threads. The First Quarto constitutes the initial appearance in print of a play --- accredited to William Shakespeare --- titled The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, but what it is exactly is unconcluded. It entered the discourse of textual scholarship in 1823 when it was “discovered,” but a satisfactory explanation of its existence has never been reached. An early popular theory was that it is an altogether different play beside the other Hamlets attributed to Shakespeare --- an adaptation of another source text entirely. The story is more similar in minutiae to the Second Quarto than the Nordic tale, but certain names and aspects of narrative, not to mention dialog, are drastically unlike the canonized idea of Hamlet. Another mostly discounted theory is that the First Quarto represents an embarrassing first draft of what would eventually be crafted into Shakespeare’s “true” Hamlet --- or that it’s even the Ur-Hamlet itself. The fashionable theory, which has given rise to the accusation that the text is a bad quarto reflecting poor authorial fidelity, is that this version of the play is a memorial reconstruction. An actor (most likely he who played Marcellus and Voltemar judging by how closely his lines resemble the dialog of the other texts) wrote down what he remembered of the play and sold it to be printed first for his own gain. Thus the consequent Second Quarto is understood as a correction and usurpation of the initial edition; an effort that presumably reflects much more authorial fidelity. It is surprising to a modern reader how unstable all of the extant material is. For example, in the Second Quarto Hamlet is considered by others a youthful student until his age is remarkably revealed to be thirty in the last act, whereas the Bad Quarto features a reasonably teenaged Hamlet. Additionally, though the title Claudius is traditionally given to the character of the King it is doubtful that any conception of Shakespeare as a singular and historical author ever thought of the King with that name. Claudius is only named as such once at the beginning of the Second Quarto and the Folio and thereafter only referenced by his position; in the Bad Quarto he is never given a name at all. When one remembers that, in the Second Quarto, eventually an attendant mentions to the King a character named Claudio, the practice of calling the King Claudius seems more like an editorial imposition based on a printer’s quirk than the reflection of one definitive play. In the Bad Quarto many of the names are what might generally be considered “nonstandard.” Our Queen Gertred, Ofelia and her father Corambis, and Montano all suggest a Hamlet as the Shakespearean manifestation of antecedent stories of Hamnet, or Hamblet, or Amleth, or Amlodi. While the names Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are, rendered thus, widely recognizable they actually represent editorially systematized interpretations --- whereas in the three major versions of the play those specific names vary significantly even within each individual text in a way resulting from and illustrating the non-codified spelling of Elizabethan drama that is almost always modernized in print. In the Bad Quarto the dialog is abbreviated and less poetic --- scenes are shuffled, revised in another context, abridged, and deleted withal. Scene fourteen, in which Horatio clandestinely plots with the Queen, is notorious because it is found in no other version. In the Bad Quarto, opportunities to confront the play’s textuality are significant and unique. Threadbare edges of the material present interpretive challenges that must be met with ardent conceptualism. After I confronted the badness of the Bad Quarto, it was given out that this misfit Hamlet, while unpopular and estranged, seems superlative in is freakishness. Hamlet refuses to cohere into something neatly definitional or a successful “organic whole” expressing an “objective correlative” --- through the lens of postmodernity the “real figure” of the greatest writer ever (the author of humanity according to Bloom) seems untranslatable; ergo I posit that we can now say Shakespeare are authors. I think through that statement much more available surface area of the work is discoverable. As Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor wrote in the introduction to the new Arden Hamlet, “If by ‘Hamlet’ we mean a public representation of a ‘Hamlet’ narrative --- that is, a story involving a character called Hamlet who has some continuity of identity with the Amlodi figure of Nordic myth --- then these three texts are just three ‘expressions’ of Hamlet out of the infinite number of Hamlets which have or could have come into existence.” The textual and narrative multiplicity of data that are available to an interpreter can enable a reaching toward the Shakespearean infinite space.

Tuesday, December 2, 2008

The Reading of The Making of Americans

The Making of the Gradual Reading of The Making of Americans

Being the History of a Reader’s Progress

by Lonely Christopher

On Sunday, November 23rd there was a congregation assembled to incite a progression through a notorious text from Gertrude Stein’s corpus that’s widely considered her swampiest and least readable: the six-hour (so-called “first installment” of a) marathon reading of The Making of Americans was staged at The Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. The event was organized by students operating under the rubric of hybrid poetics, under the instruction of writer and publisher Rachel Levitsky. This petite band had addressed works by Charles Bernstein, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, and Rachel Zolf (who visited one afternoon) but the class was to conclude by designing and undertaking a monolithic reading project. Beckett’s fiction, the theater of Brecht, and The Alphabet by Ron Silliman were among the diverse suggestions --- but we decided enthusiastically on Stein’s unruly early novel. The Making of Americans is currently available in an unabridged paperback edition from Dalkey Archive Press, but the text was long out of print (sometimes only procurable in heavily abbreviated form) and seldom read in full even by the most ardent Stein aficionados and critics. When I happened to lug my copy to class, we marveled at the blockish weight of the thing and decided the only way to enter it was to hold a drastic marathon reading. Such an approach to this text is not without precedent: Rachel recalled the 1992 Paula Cooper Gallery reading and I soon found a recording by Gregory Laynor on UbuWeb. Our reading was to be mostly localized within the Pratt community, attended only by the brave (or, fleetingly, the curious), and well documented despite its intimate scale. As the date approached I began to feel increasingly guilty about my involvement in the conception of this project. I love Stein --- my poetics wouldn’t exist if I hadn’t discovered this love --- but I can’t deny that reading her can be an excruciating experience; one that yields an intense sort of alphabetic, epiphanic gratification only after sustained engagement. I feared we wouldn’t be able to launch significantly into the 925-page galaxy of the novel in six hours because it takes me practically six months to thoroughly complete a work of hers that is a quarter of that length. Also I had never participated in a “marathon” like this --- some of us read Proust’s voluminous magnum opus once, but it took an entire summer. For me reading Stein had been a private struggle and private pleasure. I recall spending hours feverishly perusing her book How To Write after finding a fascinating rhythm while simultaneously listening to Philip Glass’ Music with Changing Parts; I remember the first time I opened Tender Buttons and was excitingly startled by the calculated abstraction of her object portraits. The Making of Americans makes monstrously adventurous use of the form of the novel; it can be said to be a “hybrid” work, I posit, even in the context of Stein’s corpus. This mammoth thing exists in a space somewhere between the psychological impressionism of Three Lives and the circular taxonomy of a piece like A Long Gay Book. As literature the novel is a rhizomatically exploded familial pastoral. The few scholars I’ve read who are familiar with the whole thing tend to point to the novel primarily as evidence of biographical specificities re Stein’s childhood. That isn’t wrong but it’s certainly also reductive. The Making of Americans isn’t about Stein’s family but about every American family. The narrative progresses sluggardly --- everything considered cyclically --- in such a way that family experience repeats until losing singularity or distinction (thus turning queer --- to invoke Stein’s usage of the term). This sort of problematizes the familiar in a way inaccessible by narratives that conflate the expansive patterned quality of American existence. Stein writes: “And then there were so many ways of considering the question […] and the many ways to look at them led to many queer things.” The reading commenced in the Pratt Institute library at 2pm. Picasso’s portrait of Stein was projected on the wall, each reader spent about twenty minutes behind the podium (although the computerized clock was broken ergo, as it was often hard to keep time when speaking through Stein, presentations ranged from ten to forty minutes), and it was frequently documented by a photographer and a filmmaker. By way of introduction, Rachel Levitsky played a recording of the author reading an extract of her novel and then the first volunteer began: “Once an angry man dragged his father along the ground through his own orchard. ‘Stop!’ cried the groaning old man at last, ‘Stop! I did not drag my father beyond this tree.’” The most pleasant discovery we made about the novel is that the reading experience, perhaps especially considering the collective atmosphere of the event, is more delightful than arduous. Stein’s prose can become overwhelming enough to cause a rupture through which readerly bliss can be accessed (this is most true of repetitive compositions like Many Many Women); The Making of Americans is so widely feared and neglected I assumed the text operated as the foremost example of that compositional technique. Yet while it certainly exists quite radically within the form of the novel, it seems that when a readerly surrender to the style is presupposed the book is, from the start, an exceptionally friendly animal. Spending six consecutive hours with it became more of a happy challenge than a malevolent punishment. Halfway through the event some of the audience had wandered off and been replaced with others, but none of the organizers appeared weary or bored (At 6pm Rachel whispered to me, “This is fun, I love this!”). I feel like I experienced the novel more than I read it --- since I didn’t always read along in my copy with the speaker, and for several hours allowed the words to wash over me gently (but, I don’t think, incidentally), I wouldn’t cite my presence at the event as proof that I “read” any of the novel (even when I was actually at the microphone speaking the words I wasn’t internalizing it on the level I would if reading in solitude). I never listen to audiobooks, and am a rather slow and deliberate reader, so my definition of the act of “reading” a text is pretty specific (conservative?). For me the event was more like an introduction to the act of reading, which was much needed considering how untroubled I have been by leaving The Making of Americans untouched on my shelf. When I presently take up the book again and read the pages that we covered during the marathon I might feel as if I’m re-tracing somewhat but I suspect that will be a welcome support (or a foundation as I study closer the aspects of the writing that I may have glossed in listening). Something else that definitely distinguishes the group reading from personal engagement with the text: each individual presenter articulated a unique delivery that shaped the meaning. Some softer and slower styles de-emphasized the cyclic patterns of the writing, bringing out buried resonances; more fragmented and particular deliveries accentuated the ungainly syntax and the gradual progression through repetition. A few casual volunteers, likely strangers to Stein’s idiosyncrasies, tripped awkwardly over the language or even became emotionally disturbed, but that was also educational. I tried to read in the usual way that I verbalize Stein: as fast as possible with extremely precise enunciation that compartmentalizes the grammar (and its queerness) while expressing a cyclic rhythm. I was fortunate to be able to read an exceptionally witty section wherein the character Julia Dehning takes daily walks with her father and tries to convince him that her suitor is worthy to marry. The extensive repetition of the dialog and its slow trudge toward minor variation (and, finally, a tentative resolution) is somehow wholly accurate in its exaggeration and exasperation. I’ve never encountered such well-conceived dialog from Stein outside of her popular novel The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. We averaged a little less than twenty pages an hour and concluded on page 108, but if making The Making of Americans was a gradual process for Stein I suppose it’s apropos that we will be gradual in our way through. To begin to conclude this summary I hereby direct the interested reader toward Stein’s essay “The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans,” from Lectures in America. It might serve as an introduction to what she’s here doing. Now: we will continue climbing the mountain of what she’s here doing as we keep making progress through the novel being a history of a family’s progress. I will finally end with a collaged extract from William H. Gass’ intoxicated foreword to the Dalky Archive edition: “[Stein] mimics the movement of life itself, aims at a target reflected in a mirror, returns, redoes […] because life belongs to the progressive present, it is living, but living is ‘same after same,’ it is variations on a theme, a deep theme, made of the mixtures of natures […] how does it happen that we feel we are present in a present our reruns make us absent from? shifting gears, poking in a purse […] if the feeling failed to materialize, we’d be as good as dead […] and every one of us will die, but only a few, a small sum at any time, can remember --- really remember --- something of some such thing: when our organs no longer peal, when our words no longer rhyme.”

Being the History of a Reader’s Progress

by Lonely Christopher

On Sunday, November 23rd there was a congregation assembled to incite a progression through a notorious text from Gertrude Stein’s corpus that’s widely considered her swampiest and least readable: the six-hour (so-called “first installment” of a) marathon reading of The Making of Americans was staged at The Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. The event was organized by students operating under the rubric of hybrid poetics, under the instruction of writer and publisher Rachel Levitsky. This petite band had addressed works by Charles Bernstein, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, and Rachel Zolf (who visited one afternoon) but the class was to conclude by designing and undertaking a monolithic reading project. Beckett’s fiction, the theater of Brecht, and The Alphabet by Ron Silliman were among the diverse suggestions --- but we decided enthusiastically on Stein’s unruly early novel. The Making of Americans is currently available in an unabridged paperback edition from Dalkey Archive Press, but the text was long out of print (sometimes only procurable in heavily abbreviated form) and seldom read in full even by the most ardent Stein aficionados and critics. When I happened to lug my copy to class, we marveled at the blockish weight of the thing and decided the only way to enter it was to hold a drastic marathon reading. Such an approach to this text is not without precedent: Rachel recalled the 1992 Paula Cooper Gallery reading and I soon found a recording by Gregory Laynor on UbuWeb. Our reading was to be mostly localized within the Pratt community, attended only by the brave (or, fleetingly, the curious), and well documented despite its intimate scale. As the date approached I began to feel increasingly guilty about my involvement in the conception of this project. I love Stein --- my poetics wouldn’t exist if I hadn’t discovered this love --- but I can’t deny that reading her can be an excruciating experience; one that yields an intense sort of alphabetic, epiphanic gratification only after sustained engagement. I feared we wouldn’t be able to launch significantly into the 925-page galaxy of the novel in six hours because it takes me practically six months to thoroughly complete a work of hers that is a quarter of that length. Also I had never participated in a “marathon” like this --- some of us read Proust’s voluminous magnum opus once, but it took an entire summer. For me reading Stein had been a private struggle and private pleasure. I recall spending hours feverishly perusing her book How To Write after finding a fascinating rhythm while simultaneously listening to Philip Glass’ Music with Changing Parts; I remember the first time I opened Tender Buttons and was excitingly startled by the calculated abstraction of her object portraits. The Making of Americans makes monstrously adventurous use of the form of the novel; it can be said to be a “hybrid” work, I posit, even in the context of Stein’s corpus. This mammoth thing exists in a space somewhere between the psychological impressionism of Three Lives and the circular taxonomy of a piece like A Long Gay Book. As literature the novel is a rhizomatically exploded familial pastoral. The few scholars I’ve read who are familiar with the whole thing tend to point to the novel primarily as evidence of biographical specificities re Stein’s childhood. That isn’t wrong but it’s certainly also reductive. The Making of Americans isn’t about Stein’s family but about every American family. The narrative progresses sluggardly --- everything considered cyclically --- in such a way that family experience repeats until losing singularity or distinction (thus turning queer --- to invoke Stein’s usage of the term). This sort of problematizes the familiar in a way inaccessible by narratives that conflate the expansive patterned quality of American existence. Stein writes: “And then there were so many ways of considering the question […] and the many ways to look at them led to many queer things.” The reading commenced in the Pratt Institute library at 2pm. Picasso’s portrait of Stein was projected on the wall, each reader spent about twenty minutes behind the podium (although the computerized clock was broken ergo, as it was often hard to keep time when speaking through Stein, presentations ranged from ten to forty minutes), and it was frequently documented by a photographer and a filmmaker. By way of introduction, Rachel Levitsky played a recording of the author reading an extract of her novel and then the first volunteer began: “Once an angry man dragged his father along the ground through his own orchard. ‘Stop!’ cried the groaning old man at last, ‘Stop! I did not drag my father beyond this tree.’” The most pleasant discovery we made about the novel is that the reading experience, perhaps especially considering the collective atmosphere of the event, is more delightful than arduous. Stein’s prose can become overwhelming enough to cause a rupture through which readerly bliss can be accessed (this is most true of repetitive compositions like Many Many Women); The Making of Americans is so widely feared and neglected I assumed the text operated as the foremost example of that compositional technique. Yet while it certainly exists quite radically within the form of the novel, it seems that when a readerly surrender to the style is presupposed the book is, from the start, an exceptionally friendly animal. Spending six consecutive hours with it became more of a happy challenge than a malevolent punishment. Halfway through the event some of the audience had wandered off and been replaced with others, but none of the organizers appeared weary or bored (At 6pm Rachel whispered to me, “This is fun, I love this!”). I feel like I experienced the novel more than I read it --- since I didn’t always read along in my copy with the speaker, and for several hours allowed the words to wash over me gently (but, I don’t think, incidentally), I wouldn’t cite my presence at the event as proof that I “read” any of the novel (even when I was actually at the microphone speaking the words I wasn’t internalizing it on the level I would if reading in solitude). I never listen to audiobooks, and am a rather slow and deliberate reader, so my definition of the act of “reading” a text is pretty specific (conservative?). For me the event was more like an introduction to the act of reading, which was much needed considering how untroubled I have been by leaving The Making of Americans untouched on my shelf. When I presently take up the book again and read the pages that we covered during the marathon I might feel as if I’m re-tracing somewhat but I suspect that will be a welcome support (or a foundation as I study closer the aspects of the writing that I may have glossed in listening). Something else that definitely distinguishes the group reading from personal engagement with the text: each individual presenter articulated a unique delivery that shaped the meaning. Some softer and slower styles de-emphasized the cyclic patterns of the writing, bringing out buried resonances; more fragmented and particular deliveries accentuated the ungainly syntax and the gradual progression through repetition. A few casual volunteers, likely strangers to Stein’s idiosyncrasies, tripped awkwardly over the language or even became emotionally disturbed, but that was also educational. I tried to read in the usual way that I verbalize Stein: as fast as possible with extremely precise enunciation that compartmentalizes the grammar (and its queerness) while expressing a cyclic rhythm. I was fortunate to be able to read an exceptionally witty section wherein the character Julia Dehning takes daily walks with her father and tries to convince him that her suitor is worthy to marry. The extensive repetition of the dialog and its slow trudge toward minor variation (and, finally, a tentative resolution) is somehow wholly accurate in its exaggeration and exasperation. I’ve never encountered such well-conceived dialog from Stein outside of her popular novel The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. We averaged a little less than twenty pages an hour and concluded on page 108, but if making The Making of Americans was a gradual process for Stein I suppose it’s apropos that we will be gradual in our way through. To begin to conclude this summary I hereby direct the interested reader toward Stein’s essay “The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans,” from Lectures in America. It might serve as an introduction to what she’s here doing. Now: we will continue climbing the mountain of what she’s here doing as we keep making progress through the novel being a history of a family’s progress. I will finally end with a collaged extract from William H. Gass’ intoxicated foreword to the Dalky Archive edition: “[Stein] mimics the movement of life itself, aims at a target reflected in a mirror, returns, redoes […] because life belongs to the progressive present, it is living, but living is ‘same after same,’ it is variations on a theme, a deep theme, made of the mixtures of natures […] how does it happen that we feel we are present in a present our reruns make us absent from? shifting gears, poking in a purse […] if the feeling failed to materialize, we’d be as good as dead […] and every one of us will die, but only a few, a small sum at any time, can remember --- really remember --- something of some such thing: when our organs no longer peal, when our words no longer rhyme.”

Labels:

essay,

Gertrude Stein,

literature

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Re Several Readings

The 20th through the 23rd of November constituted an exhausting extended weekend of differently purposed readings. It began when Robert Snyderman and I attended an appearance by Bruce Andrews and Cris Cheek hosted by The Poetry Project at St. Marks Church. Events there are always enjoyed. Bruce was very friendly and read well --- Robert thought he made “good use of the microphone.” Cris Cheek was wearing a dress, which I was informed is a kilt, and his was sort of layered, performative, hybridized work that I was glad to become introduced to. I’m afraid I damaged myself pretty thoroughly with red wine at a small, friendly gathering later where I demonstrated an absence of moderation and skirted misadventure. I vaguely remember some words on about Hamlet with Mr. Cheek; my teeth were most likely purple by then. I was in terrible shape the next day and, uncharacteristically, was unable (too nauseous) to drink during our customary Thursday night salon/reading series, which ended up being kind of rough. On Friday we had to pack into a van and travel to Vermont for a Corresponding Society appearance at Bennington, Saturday was mostly spent driving home (except for a trip to Robert Frost’s house, which we couldn’t afford to tour), and on Sunday I participated in a six-hour marathon reading of Stein’s The Making of Americans (to be addressed in-depth in a forthcoming entry). The Bennington College event was decidedly enjoyable for its participants. The featured readers were Correspondence editors Greg Afinogenov, Robert Snyderman, Lonely Christopher, Adrian Shirk, and Christopher Sweeney along with contributors Matthew Daniel and Katie Przybylski. Bennington, Vermont is a distant land surrounded by lumpy yellow fields and purple mountains; the drive from Brooklyn was pleasant despite several run-ins with police who didn’t take kindly to a bunch of kids listening to Puccini in a speeding car with expired insurance and registration. Bennington College is an adorable place where students are encouraged by the administration to engage in safe sex, drink recreationally, and start contained fires. The reading was held in a gorgeous, well-furnished room with a fireplace and a quaint stereo system we utilized to play Grieg records on a loop. Several readers stayed behind and were never heard from again. We are eager to repeat the experience at different schools and will presently attempt to organize something else. This veritable spree of readings would be even more protracted if the Unnamable Books event hosted by Adrian Shirk wasn’t delayed indefinitely, but alack. It will be rescheduled and when it is it will be noted here.

Labels:

Correspondence,

Miscellaneous,

poetics

Monday, November 17, 2008

Readings

An upcoming appearance by The Corresponding Society:

The Corresponding Society at Bennington College

Venue: The Welling Living Room at Bennington

Location: One College Drive, Bennington, Vermont

Date: Friday, November 21st

Time: 9pm-10:30pm

(&) Other forthcoming readings of interest:

Gertrude Stein Marathon at the Pratt Institute

Venue: The Alumni Reading Room at the library of the Pratt Institute

Location: 200 Willoughby Avenue, Brooklyn

Date: Sunday November 23rd

Time: 2pm-8pm

Description: In spirit of the epic 1992 Paula Cooper Gallery marathon reading, we invite you to the first installment of THE MAKING OF AMERICANS: a six-hour vocalizing of Gertrude Stein's most unread work. Stop by the Alumni Reading Room any time from 2 until 8 to listen, or sign up to read for a 10-minute time slot by e-mailing Jenna at jly1027@gmail.com.

Making Skeletons Dance

Venue: Unnamable Books

Location: 456 Bergen Street, Brooklyn

Date: Tuesday November 25th

Time: 8pm-9pm

Description: A reading series with familial themes, hosted by Robert Balkavich and Correspondence editor Adrian Shirk, featuring Ian Alexander McKenzie, Shannon Harrison, Lonely Christopher, & others.

The Corresponding Society at Bennington College

Venue: The Welling Living Room at Bennington

Location: One College Drive, Bennington, Vermont

Date: Friday, November 21st

Time: 9pm-10:30pm

(&) Other forthcoming readings of interest:

Gertrude Stein Marathon at the Pratt Institute

Venue: The Alumni Reading Room at the library of the Pratt Institute

Location: 200 Willoughby Avenue, Brooklyn

Date: Sunday November 23rd

Time: 2pm-8pm

Description: In spirit of the epic 1992 Paula Cooper Gallery marathon reading, we invite you to the first installment of THE MAKING OF AMERICANS: a six-hour vocalizing of Gertrude Stein's most unread work. Stop by the Alumni Reading Room any time from 2 until 8 to listen, or sign up to read for a 10-minute time slot by e-mailing Jenna at jly1027@gmail.com.

Making Skeletons Dance

Venue: Unnamable Books

Location: 456 Bergen Street, Brooklyn

Date: Tuesday November 25th

Time: 8pm-9pm

Description: A reading series with familial themes, hosted by Robert Balkavich and Correspondence editor Adrian Shirk, featuring Ian Alexander McKenzie, Shannon Harrison, Lonely Christopher, & others.

Sunday, November 9, 2008

Response from a Happy City

Lonely Christopher (web editor) mentions or comments on anecdotally the following aspects of last week: atmospheric excitement, public spectacle, holograms, 1968, hipsters under arrest, constitutional discrimination, preventing Asian land ownership, emotional vulnerability, the machinations of political power, a malevolent nincompoop, the same shit on a different day, bullshit that makes one feel better, a stupid car on fire in the middle of the road.

A collective nervous excitement was temporarily demonstrated in New York City last week --- during the time the polls were open and the subsequent exceptional day or two. Shortly after dusk on Tuesday, a varied assortment of individuals were already crying and yelling in the street. (I learned that Ohio was called for Obama from a kid running by on the sidewalk, screaming in disbelief into his phone, as I sat outside with my computer, trying to pick up a wireless signal to check The New York Times online.) Halloween seemed like an unenthusiastic rehearsal compared to the public spectacle that ensued that night. Members of The Corresponding Society spent the evening in a small apartment, equipped with television and Internet access, crowded with drunk and anticipatory students. The coverage of the election results was rather depraved in its theatricality --- but maybe it only seemed so nightmarish because I haven’t been exposed to news networks in several years (do people routinely appear for televised interviews via hologram these days or was that some bizarre novelty?). The neighborhood of Brooklyn in which I reside, Bed-Stuy, erupted in rowdy celebratory gestures upon the announcement of Obama’s victory. When CNN declared the win, I was on the phone arguing with my Republican mother about the political unrest of 1968. (She mentioned, “I married your father in ’68 and later he was flying planes over Vietnam.”) Our packed room of students watched McCain’s dignified concession speech, followed by Obama’s sort-of-general but incredibly-important-seeming address; then we drank a few bottles of champagne and sat out on the stoop to listen to the ruckus in the street. Outside: black Brooklyn residents expressed feelings of empowerment, white hipsters were beaten and arrested in Williamsburg, apparently there was some dancing on buses, and somewhere on Staten Island a few white thugs jumped out of a car and attacked a black kid on his way to his mother’s house. As far as the sweeping Democratic victories, the night seemed an indication that our country is capable of reforming after an awful decline into villainy --- but the occasion was also gravely marked by the establishment of discriminatory measures that will surely retard the social and cultural development of our nation. On a night when Barack Obama became the first president elect to include homosexuals in his acceptance speech, three states voted for constitutional bans on same-sex marriage (and I hear tell Florida decided to retain the antiquated legislative ability to prevent Asians from owning land, which is also unbelievable). Regardless, New Yorkers were walking around in a pleasant daze on Wednesday with an emotional vulnerability resulting from the shock of something tremendously positive actually happening in the political system. It was as if every smiling stranger was constantly poised to yelp, “Obama!” --- and his name did frequently punctuate all manners of daily activity. Reactions from our community of young writers were and continue to be more taciturn, but nobody is displeased about the general outcome. We are a group apart from the machinations of political power but we remain aware of how misdirected our country became under the Republican regime that was, for eight years, ostensibly led by a malevolent nincompoop. I was waiting for a slice of pizza last Wednesday when a woman ran into the parlor and screamed at the proprietor, “We won!” The man, kneading dough at the counter, looked at her wearily and replied, “I don’t know lady --- I woke up this morning in the same goddamn world as ever.” Maybe more optimistically, I overheard a fellow poet say, in apropos of Barack Obama’s win, “I know it’s all bullshit but it makes me feel better.” It’s difficult to provoke the city for long; nearing a week later everything has settled again. A car on fire in the middle of the road isn’t, as it was when I saw it on Wednesday, a car on fire in the middle of the road in a country that just elected a significantly atypical politician to serve as the next president, but simply a stupid old car on fire in the middle of the road that’s annoyingly blocking traffic.

A collective nervous excitement was temporarily demonstrated in New York City last week --- during the time the polls were open and the subsequent exceptional day or two. Shortly after dusk on Tuesday, a varied assortment of individuals were already crying and yelling in the street. (I learned that Ohio was called for Obama from a kid running by on the sidewalk, screaming in disbelief into his phone, as I sat outside with my computer, trying to pick up a wireless signal to check The New York Times online.) Halloween seemed like an unenthusiastic rehearsal compared to the public spectacle that ensued that night. Members of The Corresponding Society spent the evening in a small apartment, equipped with television and Internet access, crowded with drunk and anticipatory students. The coverage of the election results was rather depraved in its theatricality --- but maybe it only seemed so nightmarish because I haven’t been exposed to news networks in several years (do people routinely appear for televised interviews via hologram these days or was that some bizarre novelty?). The neighborhood of Brooklyn in which I reside, Bed-Stuy, erupted in rowdy celebratory gestures upon the announcement of Obama’s victory. When CNN declared the win, I was on the phone arguing with my Republican mother about the political unrest of 1968. (She mentioned, “I married your father in ’68 and later he was flying planes over Vietnam.”) Our packed room of students watched McCain’s dignified concession speech, followed by Obama’s sort-of-general but incredibly-important-seeming address; then we drank a few bottles of champagne and sat out on the stoop to listen to the ruckus in the street. Outside: black Brooklyn residents expressed feelings of empowerment, white hipsters were beaten and arrested in Williamsburg, apparently there was some dancing on buses, and somewhere on Staten Island a few white thugs jumped out of a car and attacked a black kid on his way to his mother’s house. As far as the sweeping Democratic victories, the night seemed an indication that our country is capable of reforming after an awful decline into villainy --- but the occasion was also gravely marked by the establishment of discriminatory measures that will surely retard the social and cultural development of our nation. On a night when Barack Obama became the first president elect to include homosexuals in his acceptance speech, three states voted for constitutional bans on same-sex marriage (and I hear tell Florida decided to retain the antiquated legislative ability to prevent Asians from owning land, which is also unbelievable). Regardless, New Yorkers were walking around in a pleasant daze on Wednesday with an emotional vulnerability resulting from the shock of something tremendously positive actually happening in the political system. It was as if every smiling stranger was constantly poised to yelp, “Obama!” --- and his name did frequently punctuate all manners of daily activity. Reactions from our community of young writers were and continue to be more taciturn, but nobody is displeased about the general outcome. We are a group apart from the machinations of political power but we remain aware of how misdirected our country became under the Republican regime that was, for eight years, ostensibly led by a malevolent nincompoop. I was waiting for a slice of pizza last Wednesday when a woman ran into the parlor and screamed at the proprietor, “We won!” The man, kneading dough at the counter, looked at her wearily and replied, “I don’t know lady --- I woke up this morning in the same goddamn world as ever.” Maybe more optimistically, I overheard a fellow poet say, in apropos of Barack Obama’s win, “I know it’s all bullshit but it makes me feel better.” It’s difficult to provoke the city for long; nearing a week later everything has settled again. A car on fire in the middle of the road isn’t, as it was when I saw it on Wednesday, a car on fire in the middle of the road in a country that just elected a significantly atypical politician to serve as the next president, but simply a stupid old car on fire in the middle of the road that’s annoyingly blocking traffic.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

A Letter on Election Day

Maybe if students reemerged as an actualized, politicized network of organized assemblages the apathetic disunity and ennui that broadly characterizes us would develop into the tenacious need for a paradigmatic shift and renegotiation of hegemonic structures that informed the widespread and revolutionary unrest that reached its crescendo in 1968. Students probably aren’t as pathetically dependent as the general on the crutch of false security (an artifice in exchange for which many acquiesce to the machinations of regimes of power that offer the public, to placate in order to subordinate, but a hollow parody of what they think they need); ergo the student is possibly capable of a critically informed perspective less structured by fear instilled by whatever system perpetuates the hegemonic pressure at the time. This has been the first presidential election that I’ve been aware enough of to be ravaged by (those previously I’ve lived through I’ve experienced with sluggardly developing recognition, but have also spent most of my life being a dumb kid in a rural town); the damage wasn’t extensive enough to lead to total self-destruction because I don’t have access to television and (myopically) rely mostly on the coverage in The New York Times and The New Yorker to inform my political understanding. What I feel I witnessed was a sort of extended carnival, in the specific sense, during which some of the more dangerous and ugly of our expressions of national backwardness were flamboyantly paraded about in the manner of a vicious pageant at the end of the world. My mother, with whom I’ve had increasingly frustrated topical confrontations in the previous months, pointed out to me that this is a historically significant election in our textbook history. In New York City (which is practically a noncontiguous territory of the United States), in my daily academic environment, I have been exposed to an implicit support of the candidate we perceive as not as dastardly as his opponent --- but the typical treatment of this election by my peers, co-workers, and the faculty of my school wasn’t really politically sensitive or adamant: we just knew that one candidate was totally preferable (and could barely conceive of a being stupid enough to think the opposite) but were generally preoccupied by the farcical crudeness of the spectacle that was readily viewable on the Internet. I personally imagine that the next president is going to have a tremendous role in determining what happens to and in our disgraced superpower; withal it sort of seems as if the general is struggling painfully toward a perspective that in some obscure way represents our position in the 21st Century rather than some frightening alternate universe. The relative liberty enjoyed by most students in this country might appease us, enabling our disinterest at a time when war is the normative state and our culture becomes ever disabled, but I don’t know what measures (voting? solidarity? taking over the campus gymnasium for a few self-important days?) could contextualize a student position in the national political discourse. The community of writers in which I participate is a very politically problematic/ambiguous group of students: almost all of us lack any sense of a political praxis (although our work is inevitably politicized); a faction of us declined to vote in this election for various reasons (from apathy to nihilism and beyond) --- I don’t know exactly what that means. I don’t presume to defend or really criticize this position and I envision the idea of a political actualization of students without positing it as imperative. Living as artists in New York City we are rather culturally/politically/ideologically divorced from the general and, in that way, are unaccredited expatriates (yet not the Beckettian kind involving underground resistance) --- still, like the revered expatriates of high modernism, our ability to function as artists is menaced by the enforcement of fascist politics. So nobody (except for Sweeney, but that’s too disturbing and complicated to really address here) wants the US to become more fascistic. At this writing I am casually uncertain about the outcome of the election --- knowing that the general is troubled enough to perform as it did four years ago and that the government is structured to enable an outrageous calamity as it did eight years ago --- withal I’m incapable of a developed position on the absence of the student in political discourse (which possibly is the result of the hegemonic political system being incongruous with a critical grammar of the student or artist). Whatever happens I will presently sit down and write a poem and that poem will not be about the recently decided presidential election but, unavoidably, it will be a poem by a writer informed (evidently and unconsciously) by his sociopolitical orientation, which happens to be especially complicated right now. (Lonely Christopher, web editor)

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Upon Directing Hamlet

Tom Newman: Hamlet isn't just Hamlet. Oh no, no, no. Oh, no. Hamlet is me. Hamlet is Bosnia. Hamlet is this desk. Hamlet is the air. Hamlet is my grandmother. Hamlet is everything you ever thought about sex, about geology…

Joe Harper: Geology?

Tom Newman: In a very loose sense, or course.

--- from Kenneth Branagh’s In the Bleak Midwinter

I’ve never seen the film in which the above lines are delivered but, out of context, they seem to me to address the greatness of Hamlet. The exchange not only suggests the multiplicity of the play but also the meta-textual arena through which we must experience it. Hamlet isn’t singularly profound according to an “objective” literary valuation --- we make it great (I couldn’t decide whether to italicize “we” or “make” right there). Appreciation of Shakespeare’s writing is often directed (imposed?) by academic context but, better looked into, the apparatus of valuation becomes as complicated and informative as the work (in its “central” position --- though I use the idea of centrality tentatively because the two aspects that perpetuate the text are probably inseparable and centrifugal). As a director I have developed an approach to Hamlet that I’m now applying through performance; I have come to understand that unqualified awe must be eschewed with deconstructive rigor in a movement toward significant awareness of the play. Since actors that I work with tend to be more comfortable with a process reliant on psychological causality and empathy it’s a challenge to expect them to be able to apply conceptualism that dislodges a motivational approach. Example: my sense of the “character” of Hamlet, developed by protracted close readings through various critical lenses, became more of a critique of coherent identity (or a positive recasting of Eliot’s complaints predicated on an attachment to an “objective correlative”) that reinterpreted Hamlet’s conflict as a schizophrenic fragmentation of selves unable to properly conflate within the dramatic context of the play. That’s a terribly devilish, maybe nearly impossible, intellectualization to ask an actor to viscerally express. Yet, according to a formalist reading, performative identity is a major theme. It’s not a matter of striking a balance between the soldier, courtier, and scholar that are remarked to be all in him --- Hamlet must also be an intertextual being; he must somehow also be this desk. One of the many stylistic/thematic choices we’ve made in rehearsals is to represent Yorrick’s skull with a large mirror that Hamlet stands in front of as he recites his famous lines --- upon considering death’s invalidation of personal existence Hamlet is facing not only a reflection of himself but of the entire audience seated behind him. The thematic conflation that constitutes the skull unfolds into a visualized network of meaning that encompasses not just the fictive situation of the drama but also the context of the production itself. This is the most challenging project I have ever attempted in my life. Although I work often as an (autodidactic) director, I am a writer, both by vocation and education, and feel most operational when embracing the gifts of solitude and interiority that practitioners of my craft tend to put to best use. The collaborative plane on which theater occurs messily affronts my abilities of artistic expression in ways both destabilizing and engaging. The writer’s struggle is private and intellectual while the director’s is discursive and interpersonal. In rehearsal the other day I had to instruct an actor how to move as slow as possible across the stage, without ever standing still, while carrying a very heavy and gnarled tree trunk on his back and delivering lines --- the experience, uncannily, felt like a literalized rendition of the introverted endeavor of the writer in a way that used the interactive grammar of performance. The aspect of theater that I most enjoy when I direct is watching and shaping the relational movement of bodies and beings articulating a text in exciting ways. While watching actors find their way through the material and across the stage with each other, when it really works, I sometimes find myself unable to remain still and begin to pace eagerly in the shadows where I attentively observe. Putting on Hamlet is a way of becoming Hamlet; maybe that’s as much a part of the thing as reading it and thinking about it.

(Lonely Christopher, web editor.)

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Developments

Here are two things, briefly:

1) Correspondence no. 1 is now available for sale at Unnameable Books of Brooklyn.

2) There have been recent entries to The Corresponding Society Author Catalog. There are a bunch of essays and interviews on the Lonely Christopher page and the new Greg Afinogenov page features translations of Russian poetry.

1) Correspondence no. 1 is now available for sale at Unnameable Books of Brooklyn.

2) There have been recent entries to The Corresponding Society Author Catalog. There are a bunch of essays and interviews on the Lonely Christopher page and the new Greg Afinogenov page features translations of Russian poetry.

Saturday, October 18, 2008

Issues

The stated deadline for submissions to Correspondence no. 2 is past but we’re still receptive of work for consideration and won’t disqualify based on negligible tardiness. Despite a particular tendency to prolong the submission period waiting for the procrastinators, who presumably wade in the river Lethe and consequently delay our optimistic schedules through their pathology, we’ve already accrued a cache of shiny new work to benefit our happy second issue. I can’t say how long we’ll be capable of regarding late submissions but it’s possibly appropriate to clarify the somewhat nominal quality of the deadline to alleviate the anxiety of the excusably delayed while encouraging those unaware of the opportunity. It’s early yet to estimate when the book will be prepared but we’re ready to assert the unlikelihood of offensively long delays. Submissions received so late that they miss the nebulous, implied, but unspecific deadline-like timeframe won’t be able to be reviewed and it’s the dilatory writer’s own fault, sort of. The submission guidelines can be found here. Please note that submitting multiple files is extremely unhelpful --- we’d prefer the work all in one .doc file, thank you.

We begin work on our next project but Correspondence no. 1 remains available through methods of purchase both convenient and convoluted. For those favoring ease of use, we now sell Correspondence online, by Paypal, through the store on our website. For those deathly afraid of a newfangled confusion like Paypal we would like to mention that we generously continue to accept orders through the postal service (just email us at thecorrespondingsociety [at] gmail.com with your address and we’ll reply in kind). This issue includes an essay on the rhetoric of the Apocalypse, a poem with the line, “the book goes in the fire like an internet of seaweed round his cock,” a savage explosion of Persephone’s myth, the entire alphabet, a demand for poetry by Richard Loranger, and much else unfamiliar. It’s also probably still available at the Bowery Poetry Club and through Poem Shop.

We begin work on our next project but Correspondence no. 1 remains available through methods of purchase both convenient and convoluted. For those favoring ease of use, we now sell Correspondence online, by Paypal, through the store on our website. For those deathly afraid of a newfangled confusion like Paypal we would like to mention that we generously continue to accept orders through the postal service (just email us at thecorrespondingsociety [at] gmail.com with your address and we’ll reply in kind). This issue includes an essay on the rhetoric of the Apocalypse, a poem with the line, “the book goes in the fire like an internet of seaweed round his cock,” a savage explosion of Persephone’s myth, the entire alphabet, a demand for poetry by Richard Loranger, and much else unfamiliar. It’s also probably still available at the Bowery Poetry Club and through Poem Shop.

Friday, October 10, 2008

Lonely Christopher in Conversation with Kenneth Goldsmith

Kenneth Goldsmith studied sculpture at RISD but has become the foremost practitioner of Conceptual Writing. He curates the invaluable archive of avant-garde material called Ubuweb, hosts a radio show on WFMU, and acts as a spokesperson for his contemporary poetics online, in print, and at academic conferences. His books are expressions of what he calls “uncreative writing”: renegotiations of the value systems upon which literature rests. The work ranges from entertaining (Soliloquy transcribes every word he said over the course of one week), to hypnotic (The Weather, a short volume, is a year’s worth of radio forecasts), to presumably readable only by madmen (the thick Day contains every character printed in one copy of The New York Times). Although he frequently suggests the idea of the texts should substitute for the experience of reading them, when somebody is inclined to make the effort she confronts a vacuum in which, paradoxically, everything is breathing with meaning. Kenneth is the subject of the 2007 documentary Sucking on Words, which is available to view online. Though I’ve heard his peers accuse him of being a confidence man, the implications of his work have been addressed extensively by poets and academicians. (Ron Silliman recalls, “I knew people were taking him seriously when, over five years ago, the MacArthur Foundation called to ask me if I thought he was a genius.”) Goldsmith teaches at the University of Pennsylvania; he edited I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews, which was the basis for an opera that premiered in March 2007. When I first met him four years ago he wasn’t wearing any shoes. The following is a transcript of a recording from last January when I sat down with him at his Manhattan home and asked him some questions (originally published in an undated issue of The Prattler circa February 2008).

Lonely Christopher: Why do you think writing is such a conservative form?

Kenneth Goldsmith: Because language is the means through which we communicate with each other. If we disrupt that communication flow then chances are, according to the conservative idea, we can never understand each other. And if we can never understand each other, in the type of way we’re speaking right now, we can’t get anywhere. Most likely we can’t do anything. We can’t make business together, for example, if we don’t have a common language. It’s very sacred to a lot of people so they get very threatened by rupture in language.

LC: You have said you no longer think of yourself as a poet or writer but as a word processor. You have also said that creativity is bankrupt. I can’t really decide whether those are pessimistic or optimistic statements, or both, but they sort of scare and excite me. Yet maybe there’s also something restrictive or tyrannical in declaring the death of creativity. What do you think about these reactions?

KG: It’s not really meant to be a provocation; it’s simply an explanation of where we happen to be at this particular time. We spend our time processing language these days. We spend our time processing everything these days. Writing needs to respond to the new environment of the web, which is all about information management. If it’s not responding to that particular situation it cannot be called contemporary.

LC: So do you think that responding to situations presented by the Internet is one of the main concerns of your work?

KG: Very much so, yeah. It’s changed the whole game, hasn’t it? Most writers, of course, don’t want to deal with it. They pretend the Internet never happened.

LC: What does sculpture mean to you and why did you quit it?

KG: I’m not sure how to answer the first part of that question.

LC: That’s the part of the question I’m more interested in.

KG: Oh, is it? Okay. In a city like this, sculpture is impractical. I came to New York as a sculptor. In a city where space and transport is at a premium I couldn’t function the way I could when I was in school when I had unlimited studio space and I could make these enormous things and show them in these big spaces and store them in another place. You come to New York and everything has to change. I think writing is the perfect solution. A sculptural approach to writing is really great. You can actually carve words, be very physical with words, and you can do it all on a laptop in a studio apartment. I think the best way to be a sculptor is to work on the computer.

LC: How do you address the materiality of the word?

KG: Words are really great. They can take any form you pour them into. If you want to make it material you can output it in a thousand different ways. You could make those words into cast iron, you could paint them, you could make dresses out of them... it never ends. On the web you can realize it materially in all other ways, the ways we were talking about with Flash or with programming. That’s the beauty of language. You can’t do that with paint. It’s much more malleable than paint. It’s a great medium.

LC: What is it about Andy Warhol that you admire?

KG: There’s nothing about Andy Warhol that I don’t admire. I think in terms of a writer the thing that struck me the most was Warhol’s sense of the contemporary; he really embraced the contemporary. And it wasn’t always pretty, but he knew he had to be of his moment. As a result, because of being such a part of his moment, he became a part of the culture and now he’s as relevant or maybe even more relevant than he was when he was alive. So I must admire his contemporariness.

LC: How does that work? When I first started thinking about Warhol I was thinking about him actually in relation to the Situationists because I was studying the Situationists and I saw that they wanted to affect change but they designed their movement in a way where all their ideas were easily colonized and they really quickly failed. That failure made me think of Warhol because he seemed to have designed his work and life in a way where whatever the position it was put in it still retained its integrity.

KG: You’re very astute; that’s a great point. But the real thing is that the secret of Warhol was he never intended resistance and therefore something that could never offer resistance could never be co-opted. That’s fucking brilliant. He was completely complicit and by being complicit he was subversive. It was a very brilliant strategy of his. He took a lot of shit for it, too. People didn’t understand.

LC: Can you tell me about the Warhol opera? I know very little about it.

KG: I did an opera based on the book of Andy Warhol interviews I edited that was performed in Geneva by a troupe of six dancers, a dozen musicians, and a bunch of opera singers. It was all chopped up text from the words of Andy Warhol.

LC: What’s the purpose of turning Warhol’s interviews into a libretto? That seems like a “creative” act in contradistinction to both your own ideas about writing and maybe even certain perceptions about the intentions of Warhol’s work.

KG: But this book was a very different type of a book: it was an art historical book, it was a different type of a project. Had this been my project I would have gathered the Andy Warhol interviews and put my name on them (simply retype them and not attribute them to Andy Warhol).

LC: What do you think about the interview as a form?

KG: That’s why that interview book with Warhol was so interesting. Because, like everything Warhol touched, it became a new way of making art for him. Warhol would do a completely untraditional interview and he would end up asking the interviewer more questions than the interviewer could ask him so by the end of the interview you found out nothing about Warhol but you found everything out about the guy who was interviewing him. He was a mirror: you just see yourself in it. He would never show you what he was.

LC: What does plagiarism mean to you?

KG: It’s a fabulous way to write. It’s a writing technique to me.

LC: What do you teach your students?

KG: I teach them plagiarism. I teach them uncreative writing. I teach them how to steal, how to appropriate, how to falsify papers, how to buy papers and call them their own. Anything that’s not allowed. We explore in the classroom and my students are penalized for showing creativity or originality.

LC: What do you think of creative writing workshops and of formalism?

KG: I think they are shit. I mean they’re bullshit. It’s fine for another time but it’s not contemporary. It has absolutely nothing to do with the world we live in right now. It’s high school stuff.

LC: Why do you think creative writing programs have become so popular?

KG: I have no idea. I have no idea why anybody would be interested in that approach. Maybe they want to go to Hollywood and write screenplays, but if you write screenplays all you’re doing is plagiarizing other screenplays and other stories anyway. They’re doing what I’m saying writing should be doing, but they’re not admitting it. Nothing’s original in Hollywood. If you made something original in Hollywood it would never get made. You have to remake the same story over and over again. But of course they can’t admit it.

LC: Can you talk about your ideas of process in relation to art and writing?

KG: Unlike painting (where the artist has to stretch a canvas, prime it, make the thing stand up) writing is a different process but I think it’s an equally intense and important process. Like you were talking about with your work: sort of building a structure, hanging the language onto it, and then letting the structure fall away. I’m a bit of a Structuralist. I’m interested in Oulipian constraints, but then in the end kind of kicking the thing away and letting it stand, like you. Very interesting.

LC: You say that people don’t have to read your books as long as they understand the ideas -- but to me, thinking about a concept of one of your books and engaging with one of them in practice (by actually reading it) are different experiences. To me the effort of reading your books, which are boring texts in a way, provides a fuller experience and a sharper understanding of what it is you are accomplishing. Why do you often suggest that reading your books is unnecessary?

KG: We let them off the hook. Text works on so many levels. There’s the level of language that we’re speaking right now, which is transparent: the language doesn’t exist; only the ideas are jumping from my mouth to your mind and from your mouth to my mind. Or else we could have a you know we could start ehh blep ek app whhwhat am I try um ep uh ahh you juhh ah start to uh hhhheh wait, you know, then suddenly we begin to think of language not as transparent but actually as physical matter. That’s the beauty of language: there’s no one way to understand it, there’s no one way to engage with it. I say you don’t have to engage with it, but I don’t say you’re not permitted to either. I think there’s another experience to be had; it’s not one many people are going to want to do, and that’s okay, that doesn’t really bother me. But I like the multi-tonality of these books. They provide a different experience to think about it and a difference experience to read it. Most books, if you don’t read it you don’t get it.

LC: I’ve heard you sometimes use languages you are not familiar with. Can you talk about that?

KG: When I first started writing I was extremely formal and I realized that by inventing a formal system you could subvert the normative uses of your native language. I was at Whole Foods yesterday and I was talking to the bagger and I had all these groceries and I said, “I’d like you to bag everything by shape or color this time, so put everything that’s red in one bag and everything that’s round in another bag.” So you have an extremely different interaction with what’s most familiar if you begin to apply a different type of structural system to it. So in that way I was able to de-familiarize my own language. I was able to actually work with English in a way where I didn’t understand English even though I understood every word. It was really interesting, organizing things by shape and color instead of by what goes in a bag together naturally. And so I figured if I could do that with my own language then I could do it with any language. And so I began using languages that weren’t mine and organizing them formally (creating a formal device by which the language would fall into place). And I was able to write in any language I wanted.

LC: How do you see groups of artists being configured now compared to earlier when New York had seemingly more vital communities predicated on geography? I feel like, to some extent, student communities that form around schools are incidental and the artistic environment of the city thirty or forty years ago that I tend to idealize has basically been erased or mostly paved over. What does the Internet have to do with this paradigmatic change?