Hamlet’s Dad from Hell

a terrific misreading

by Lonely Christopher

The villain of Hamlet is the ghost: a spectral dad beckoning his entire family to murder. Hamlet basically: a supernatural revenge thriller where some fancy-costumed royalty frown and yell in a haunted castle before they all kill each other. Every bad thing happens in the play because of the ghost, who is already menacing some poor sentinels at the very outset. Admittedly, the ghost (who undeniably exists, that is he’s not hallucinated, according to the play’s dramatic logic) happened to become so phantomy because he was murdered. Withal, the regicidal villain (his bro, ouch) forthwith assumed his victim’s crown and wife. Unfortunately for undead Old Hamlet, he was a prayer shy of heaven thus imprisoned as a disappointed wraith. Still, to apply a worn axiom, two wrongs don’t make a right. Demanding his melancholy son to perform unspecified revenge (hint: probably stabbing) has no nutritional value outside restoring nominal moral order to the court. (Restoring morality when nobody realizes the crime even happened would mean, for most involved, having to create the problem in order to solve it.) The ghost doesn’t think about the consequences and doesn’t want Hamlet to tarry either. His spooky instructions aren’t very helpful (not to mention delivered with Satanic theatrics that end up traumatizing his son) --- and even if Hamlet had immediately followed through in deposing Claudius (in such a way that was recognized as just by all), the political result would probably include being conquered by Norway. Claudius had to poison his own brother to achieve the crown, but he was diplomatically competent enough to do so in such a way that nobody suspected his crime; he also seemed to be expertly managing/resolving the threat of foreign invasion --- Hamlet doesn’t have very mature problem solving skills and, considering his mental illness withal (that is, melancholia not his fake antic disposition), his future as a leader is suspect. We know Old Hamlet was brave in combat, but if he was as reckless alive as dead, maybe Denmark ended up better off with Claudius. After “stealing” the vacant throne from Hamlet by being elected, Claudius is a little worried about further hurting his sensitive nephew’s feelings (hence telling him to drop out of school the better to be monitored at home), but otherwise he treats Hamlet like a stepfather who just wants to be liked. Meanwhile, Hamlet’s real dad is back from hell (okay, purgatory), lurking around battlements, and haunting his son screeching terrible, unfounded accusations and demands for revenge. Horatio warns that the ghost might be a disguised devil --- the kind that has fun driving melancholiacs to madness before pushing them off cliffs (it was a different time). Even if the ghost is honest that doesn’t stop him from causing a far bloodier end than a crazy leap off a cliff. Some claim that this is a play about skepticism. Olivier famously introduced his film version as a story about a man who couldn’t make up his mind. The thematic scope is larger, though, because Hamlet agonizes over more than critical indecision. The problem is so much more enormous than helping a ghost --- the problem is the nature of the ghost attack itself. When dad visits him from his nether-universe of negation, Hamlet’s brain comes unstuck from the dramatic context of this royal thriller and everything problematizes doing anything (he’s dissociated). Hamlet dearly hopes, once shuffled off this mortal coil, the rest is silence --- after his transfiguration into a failure hero, all the mental torture, and having caused the death of almost everybody around him (including two women he loved), there better be a universe of nothing but silence waiting because the joke just keeps getting worse if he ends up burning with dad in purgatory. We’ve Old Hamlet’s posthumous bad parenting to thank for the mess that makes up the play (without the ghost the action would be limited to Hamlet moping around Elsinore whining about how slutty his mom is); the revenge hungry spook is the foundational conceit of the narrative progression. Hamlet goes kind of crazy (offstage and hatless) over the problem of the ghost’s nature and purpose. He wonders if the figure of his father is a spirit of health or goblin damned. The former doesn’t really fit, considering the suicide mission the ghost pushes Hamlet into; whether demon or dead king the apparition has no concern for Hamlet’s wellbeing --- he wants to be remembered, damn it, and avenged! --- and only pokes his floaty head into the action once more to threaten to spank Hamlet for wasting time in killing more of the court (he’s not too happy about the boy slapping his mother around, either, more evidence of his selective morality). If he just slept on it another night maybe the ghost would have given Hamlet different advice: “I’m upset your uncle killed me for my wife and crown --- not to mention before my sins were forgiven, so I’m a damn ghost purging my misdeeds in flame most of the day --- but since we didn’t get to talk before brain-melting distilment was poured in my ear porches, I just want you to know I love ya. I realize you expected to be my heir when I died, but don’t let it get you down; first of all, the king is elected by popular vote, so you would have had to campaign (no fun), and also you’re still a teenager and way more interested in demonology and theater than international politics --- maybe one day, kid. And hey: I know she let us down, but take care of your mom, that slut, and be nice to your girlfriend because she’s fragile --- oh, and stay in school. Also, no big deal, but please at some point kill your uncle. Eye for an eye, right? But only when you feel ready.” Oh well! Old Hamlet wasn’t the only problem father of the play. Fortinbras’ dad was irresponsible enough to get killed (by Old Hamlet no less) in a macho land gamble and Polonius messed his daughter the fuck up and paid a spy to follow his son while spreading rumors he likes prostitutes. These hapless children, following Hamlet’s example, idolized their fathers even when doing so played directly into harm that the fathers were usually responsible for. Polonius is a real jerk to Ophelia (at least way overprotective), but she continues to love him so much that when he’s killed she goes crazy, falls out of a tree, and drowns. Fittingly, the bloodbath finale begins with a showdown between two kids with dead dads, both after bloody revenge. At that point Hamlet’s heart isn’t even in it anymore; he just wants to get it over with already. And: everyone dies. Except Horatio, he survives everybody and, coincidentally, never mentions his father the whole play.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Video Sample

Correspondence No. 3 shall arrive around the end of the year according to best estimates. Wise literates would do well to prepare for the delirious pleasure this document will bring. Really, it’s dangerous. Because we’re responsible please find below a sort of preview, which the reader might use as a patient does a flu shot to protect her body against a virus. In this example, the virus is words and also it’s a good virus. It’s just a little much and we don’t want readers to get hurt. Well, yes, emotionally we want to damage readers. We just don’t want to permanently injure them with the majuscule poetic force contained within this forthcoming volume/weapon. So here is a taste, which is a video record of Ray Ray Mitrano performing something to be found in the pages of No. 3. It is called “Italy When Three.”

Italy When Three from RAY RAY MITRANO on Vimeo.

Monday, November 9, 2009

Wide Eyes

Negative Nice

Trinie Dalton’s short fiction is darling and traumatic

by Lonely Christopher

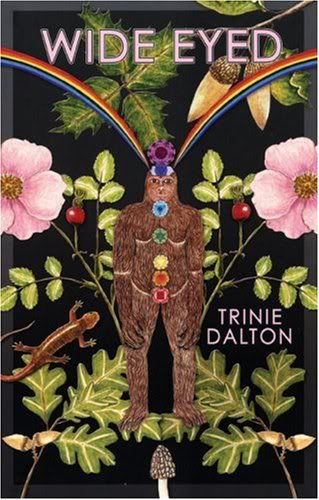

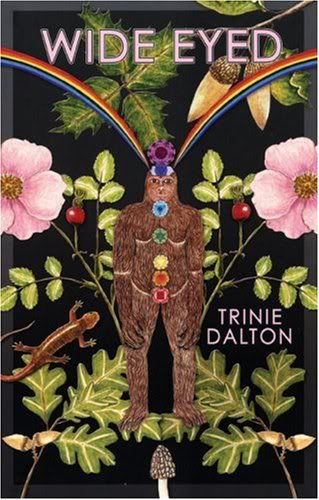

The cover art of Trinie Dalton’s book Wide Eyed, put out aught-five by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery series from Akashic, features author-drawn illustrations of flowers, rainbows, unicorns, and a bigfoot type creature. I remembered the cover from seeing it at a bookstore a while ago; when I asked a friend about it he told me the cover was a good indication of the content and now I agree. What’s funny is that the collection is so magnificent. It has so many conceptual strikes against it, worst of all being creative writing, viz. fiction, published this decade. The persistence of kitsch (unicorns, for a start), the clever randomness (whimsical unpredictability!), and the ironic cultural references (the Flaming Lips, 80’s slasher flicks, Disney) are techniques shared with hipster fiction of the most abhorrent variety (unimportantly plaguing the aughts, hipster fiction is something we’re going to have to go back in a time machine to prevent). Dalton proves the same things that we’ve seen so abused by a whole youth culture can be used without guilt with delightfully winning results. She’s too mature to ruin the form like younger kids are and too clever to ruin the form like writers her age are. This is a compliment and a joy.

Anyway, if the stories were all sugar, narrated as they are by a very similar voice and personality that’s almost a sort of Amelie from a negative dimension, this writing would be impossible to stomach. What makes it work is how a Cooper-like disgust or anxiety spoons in a frilly bed with the ingenuous cuteness. This is a pretty fucked-up book --- plus it’s adorable. The Ben Marcus blurb on the back, which only praises aspects of innocence, love, and wonder, makes me suspect either Ben Marcus didn’t read Wide Eyed or else he’s a pretty disturbed person. These stories are ugly/pretty: a sinister violence becomes the undertow in a sparkling sun-kissed lazy river. The quality of this sentence is representative: “When I was in elementary school and first learned about the realities of rape, I remember riding home on the bus from a field trip to Disneyland and wishing I had been dragged into Adventureland, then raped behind Thunder Mountain.” No other contemporary work I can think of so vividly captures a world where everything being so not okay hurts but can’t murder being a happy person.

Nobody can do anything right and even when that fact is benign it’s still a lurking threat. The obsessions with unicorns, elves, woodland and sea creatures, botany, childhood, and candy only prove the darkness of these stories, which are about the awkward pleasures of aloneness, the façade of normalcy being punctured by humanity’s underlying ugliness, and the pathological failures of people to negotiate each other cleanly. Try writing a story in pen pal letters between a lonely woman-child and an elf from the North Pole without making anybody with halfway-developed critical faculties find you and take some sort of revenge. Well, that’s not the strongest story here, but she pulled off okay the elf thing and I have no clue how (what sounds feasible about “pulling off the elf thing”?). Dalton uses the shorter short fiction form to her advantage. There was no story (most are about five pages in the largest font you can sort of get away with) I wanted to be longer. She knows how long something can go on for; depth accumulates, but each story is a few weirdly shallow gasps. The episode I found most arresting was part of an essayish triptych anecdotally describing how things, blood namely, can come to drool across floor tile. This particular section of the barely six-page piece is less than two pages; it depicts in careful/squirmy portraiture the event of a boy taking a shower in a scummy apartment and a “mutant salamander” emerging from the drain. The result is not hygienic or pleasant, but demonstrating an economy of discomfort and Lilliputian trauma.

The story of an attempt at throwing a house party begins ruined by a guest, missing a shoe, breathlessly approaching the host: “‘Your fucking friend just attacked me,’ she says. She was in my basement music room so no one heard her yelling through the egg-crate covered walls. I’m hosting a Hawaiian-themed party.” The creep who stole the girl’s shoe after harassing her is a total failure who can’t quite fit well enough into the way things go and who suffers from crippling social problems. The narrator, who herself has positive intentions (a nice luau, like what? the details of the music room being pretty heartbreaking, too), tries to understand the creep: “He didn’t seem dangerous, just fetishistic.” Another story begins similarly with the narrator and her boyfriend Matt having a “luxury” pork meal to celebrate his latest painting. The painting is “as long as a Honda, and as tall as our ceiling. Red-barked trees, squirrels, and naked women cover the canvas.” The constant miracle of this book is that it never slouches into lazy Napoleon Dynamite twee/preciousness; despite how close it comes it then swoops back into the realm of literary skill as assuredly as a stunt pilot pulling out of a nosedive right before hitting the water. The turn in this flash-length storylet is when Matt can’t stop himself from doing the “wrong” thing (he eats all the copious pork leftovers cold for breakfast: “I just ate a huge pile of lard, basically”), getting miserably ill as consequence, and the narrator can’t help but desiring him more for his disabled judgment. Elsewhere: the narrator imagining she is Snow White --- with glass coffin, singing chipmunks, and all --- during a sexual encounter in her backyard garden. The scene is tenderly pathetic and, ultimately, emotionally affirmative (hell, wide eyed). “Everything went white as I came, as if the moon suddenly got brighter.” Most of the characters in these stories act like high functioning autistics. When the simplest aspects of getting by in life are rendered as impossibly fraught, the result is highly unnerving as safety divorces from routine. The balance between childish awe and psycho nervousness is the best hit of Wide Eyed. There is no reason this book works more than that Trinie Dalton has a major handle on her craft and knows how to channel her bizarre fixations (is that me projecting?) into the kind of art that you appreciate as it makes you feel uneasy about the world.

Trinie Dalton’s short fiction is darling and traumatic

by Lonely Christopher

The cover art of Trinie Dalton’s book Wide Eyed, put out aught-five by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery series from Akashic, features author-drawn illustrations of flowers, rainbows, unicorns, and a bigfoot type creature. I remembered the cover from seeing it at a bookstore a while ago; when I asked a friend about it he told me the cover was a good indication of the content and now I agree. What’s funny is that the collection is so magnificent. It has so many conceptual strikes against it, worst of all being creative writing, viz. fiction, published this decade. The persistence of kitsch (unicorns, for a start), the clever randomness (whimsical unpredictability!), and the ironic cultural references (the Flaming Lips, 80’s slasher flicks, Disney) are techniques shared with hipster fiction of the most abhorrent variety (unimportantly plaguing the aughts, hipster fiction is something we’re going to have to go back in a time machine to prevent). Dalton proves the same things that we’ve seen so abused by a whole youth culture can be used without guilt with delightfully winning results. She’s too mature to ruin the form like younger kids are and too clever to ruin the form like writers her age are. This is a compliment and a joy.

Anyway, if the stories were all sugar, narrated as they are by a very similar voice and personality that’s almost a sort of Amelie from a negative dimension, this writing would be impossible to stomach. What makes it work is how a Cooper-like disgust or anxiety spoons in a frilly bed with the ingenuous cuteness. This is a pretty fucked-up book --- plus it’s adorable. The Ben Marcus blurb on the back, which only praises aspects of innocence, love, and wonder, makes me suspect either Ben Marcus didn’t read Wide Eyed or else he’s a pretty disturbed person. These stories are ugly/pretty: a sinister violence becomes the undertow in a sparkling sun-kissed lazy river. The quality of this sentence is representative: “When I was in elementary school and first learned about the realities of rape, I remember riding home on the bus from a field trip to Disneyland and wishing I had been dragged into Adventureland, then raped behind Thunder Mountain.” No other contemporary work I can think of so vividly captures a world where everything being so not okay hurts but can’t murder being a happy person.

Nobody can do anything right and even when that fact is benign it’s still a lurking threat. The obsessions with unicorns, elves, woodland and sea creatures, botany, childhood, and candy only prove the darkness of these stories, which are about the awkward pleasures of aloneness, the façade of normalcy being punctured by humanity’s underlying ugliness, and the pathological failures of people to negotiate each other cleanly. Try writing a story in pen pal letters between a lonely woman-child and an elf from the North Pole without making anybody with halfway-developed critical faculties find you and take some sort of revenge. Well, that’s not the strongest story here, but she pulled off okay the elf thing and I have no clue how (what sounds feasible about “pulling off the elf thing”?). Dalton uses the shorter short fiction form to her advantage. There was no story (most are about five pages in the largest font you can sort of get away with) I wanted to be longer. She knows how long something can go on for; depth accumulates, but each story is a few weirdly shallow gasps. The episode I found most arresting was part of an essayish triptych anecdotally describing how things, blood namely, can come to drool across floor tile. This particular section of the barely six-page piece is less than two pages; it depicts in careful/squirmy portraiture the event of a boy taking a shower in a scummy apartment and a “mutant salamander” emerging from the drain. The result is not hygienic or pleasant, but demonstrating an economy of discomfort and Lilliputian trauma.

The story of an attempt at throwing a house party begins ruined by a guest, missing a shoe, breathlessly approaching the host: “‘Your fucking friend just attacked me,’ she says. She was in my basement music room so no one heard her yelling through the egg-crate covered walls. I’m hosting a Hawaiian-themed party.” The creep who stole the girl’s shoe after harassing her is a total failure who can’t quite fit well enough into the way things go and who suffers from crippling social problems. The narrator, who herself has positive intentions (a nice luau, like what? the details of the music room being pretty heartbreaking, too), tries to understand the creep: “He didn’t seem dangerous, just fetishistic.” Another story begins similarly with the narrator and her boyfriend Matt having a “luxury” pork meal to celebrate his latest painting. The painting is “as long as a Honda, and as tall as our ceiling. Red-barked trees, squirrels, and naked women cover the canvas.” The constant miracle of this book is that it never slouches into lazy Napoleon Dynamite twee/preciousness; despite how close it comes it then swoops back into the realm of literary skill as assuredly as a stunt pilot pulling out of a nosedive right before hitting the water. The turn in this flash-length storylet is when Matt can’t stop himself from doing the “wrong” thing (he eats all the copious pork leftovers cold for breakfast: “I just ate a huge pile of lard, basically”), getting miserably ill as consequence, and the narrator can’t help but desiring him more for his disabled judgment. Elsewhere: the narrator imagining she is Snow White --- with glass coffin, singing chipmunks, and all --- during a sexual encounter in her backyard garden. The scene is tenderly pathetic and, ultimately, emotionally affirmative (hell, wide eyed). “Everything went white as I came, as if the moon suddenly got brighter.” Most of the characters in these stories act like high functioning autistics. When the simplest aspects of getting by in life are rendered as impossibly fraught, the result is highly unnerving as safety divorces from routine. The balance between childish awe and psycho nervousness is the best hit of Wide Eyed. There is no reason this book works more than that Trinie Dalton has a major handle on her craft and knows how to channel her bizarre fixations (is that me projecting?) into the kind of art that you appreciate as it makes you feel uneasy about the world.

Monday, November 2, 2009

Word's Way

From our friends at Republic Brooklyn:

REPUBLIC Worldwide Presents

WAY OF THE WORD

Wednesday November 11, 2009

7 pm-11 pm

Bar On A

170 Avenue A (between 10th St & 11th St)

It is in the spirit of language arts that REPUBLIC presents the first installment of its recurring “Way of the Word” program at Bar On A.

WAY OF THE WORD is a unique evening of art, poetry, performance and music by emerging artists in the New York poetry world.

Visual Poets include: Edward Hopely, Brian VanRemmen and more

Slam poets: Khephran Riddick and Aldrin Valdez

Traditional poets: Davey Vacek, Katie Przybylski, Marissa Forbes, Peter Ford, and three founding members of a Brooklyn based poetry group called The Corresponding Society --- Lonely Christopher, Robert Snyderman, and Jason Tallon.

Doors open at 7pm with a visual and interactive gallery hour for the artists, poets, and guests before the poetry readings begin at 8pm.

Drink specials from 7 to 9pm. Bar On A

“Way of the Word” represents the idea that words take on wills of their own, depending on how they’re put on the page and how a reader perceives them. A short event anthology, featuring poets from the show and around the nation will be available for purchase online and at the door for $15.

Portions of the proceeds will be donated to Reading Excellence and Discovery (READ), a foundation that promotes literacy by pairing qualified high school tutors with elementary students who demonstrate below grade level reading skills.

For more information about “Way of the Word,” READ or REPUBLIC please contact jason@republicbrooklyn.com or call 443. 528. 6761 or 917. 273. 2712

REPUBLIC Worldwide Presents

WAY OF THE WORD

Wednesday November 11, 2009

7 pm-11 pm

Bar On A

170 Avenue A (between 10th St & 11th St)

It is in the spirit of language arts that REPUBLIC presents the first installment of its recurring “Way of the Word” program at Bar On A.

WAY OF THE WORD is a unique evening of art, poetry, performance and music by emerging artists in the New York poetry world.

Visual Poets include: Edward Hopely, Brian VanRemmen and more

Slam poets: Khephran Riddick and Aldrin Valdez

Traditional poets: Davey Vacek, Katie Przybylski, Marissa Forbes, Peter Ford, and three founding members of a Brooklyn based poetry group called The Corresponding Society --- Lonely Christopher, Robert Snyderman, and Jason Tallon.

Doors open at 7pm with a visual and interactive gallery hour for the artists, poets, and guests before the poetry readings begin at 8pm.

Drink specials from 7 to 9pm. Bar On A

“Way of the Word” represents the idea that words take on wills of their own, depending on how they’re put on the page and how a reader perceives them. A short event anthology, featuring poets from the show and around the nation will be available for purchase online and at the door for $15.

Portions of the proceeds will be donated to Reading Excellence and Discovery (READ), a foundation that promotes literacy by pairing qualified high school tutors with elementary students who demonstrate below grade level reading skills.

For more information about “Way of the Word,” READ or REPUBLIC please contact jason@republicbrooklyn.com or call 443. 528. 6761 or 917. 273. 2712

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)