Warhol Speaks for Himself, Kinda

by Lonely Christopher

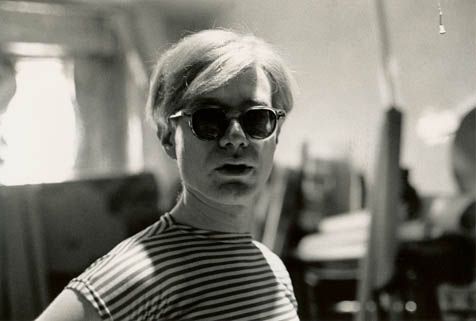

Andy Warhol is intellectual property to which we all share the copyright. After staging a play about Andy Warhol in a rural Pennsylvanian town, the local audience approached me with about the same ideas on the subject as articulated by anyone I’ve talked to about it within academia or bohemia. “Andy Warhol’s whole life wassis work, ya’know, so he became some sorta performance, an anti-human er anti-artist, like he turned everything he saw inta art so it done mean nothin. He took th’ image an emptied it all out, so it were just all on th’ surface. Like, he didn’t see no depth in nothin’ --- so his art was turnin’ everything inta culture, inta an empty signifier, doncha know. I’d say, shucks, Warhol has gone the furthest in the annihilation of th’ artistic and th’ creative act; he was uh simulacrum.” Andy Warhol is as egalitarian as Coca-Cola, a soft drink that he appreciated because its popularity meant some bum on the street drank exactly the same Coke as Elizabeth Taylor. Warhol is an American invention. Andy: “That could be […] the best American invention --- to be able to disappear.” A has disappeared into complete ubiquity. We talk about Warhol and mean nothing. I chewed up Baudrillard’s essay on Andy (“Machinic Snobbery,” from The Perfect Crime) and collaged its pulpy guts into my play, along with sources like Kenny Goldsmith’s edition of A’s selected interviews. I interviewed Kenneth once and we talked some about Warhol. LC: “How does that work? When I first started thinking about Warhol I was thinking about him actually in relation to the Situationists because I was studying the Situationists and I saw that they wanted to effect change but they designed their movement in a way where all their ideas were easily colonized and they really quickly failed. That failure made me think of Warhol because he seemed to have designed his work and life in a way where whatever the position it was put in it still retained its integrity.” KG: “You’re very astute; that’s a great point. But the real thing is that the secret of Warhol was he never intended resistance and therefore something that could never offer resistance could never be co-opted. That’s fucking brilliant. He was completely complicit and by being complicit he was subversive. It was a very brilliant strategy of his. He took a lot of shit for it, too. People didn’t understand.” My play, I Am Happy, is about a major problematic in studying Warhol: the man/machine dichotomy, which seems to be unresolved. The premise: an interviewer questions A, vomiting about the artist qua sign system before doubling back and suspiciously interrogating that position (receiving only vaguely bored and clever answers from his subject). He sits frustrated over A (who pushes pills across the surface of a mirror); frowns: “A lot of people are inclined to put you down because you operate at a certain distance --- mechanically, artificially. And yet it is claimed you are not, cannot be, truly a mutant. You are made of the same material as everyone else, you are not yourself a mirror or a machine --- but regular blood and guts (violence being your threatened reminder, ugliness your secret humiliation). Doesn’t this problematize addressing you as some sort of text, sign system, or an object? […] Is [your] mechanic affectation rather an adaptive mythopoetics?” A says, as usual, “I don’t know.” Upon studying Kenny’s collection of documents for the first time, the actual interviews, I learned a valuable lesson re the importance of not knowing (even if you do). I like reading theorists, biographers, and memoirists inscribing Warhol for themselves (and us) in various texts. Baudrillard denies biography, or the very embodiment of the idea of Warhol; Koestenbaum (in a monograph for Penguin) attempts to invoke a tortured and imaginative sexuality for his subject; Coacello often uses Warhol to define and validate his own narrative (Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up); Bockris (The Life and Death of Andy Warhol) constructs A as the classic biographer’s subject, portraying him historically like a dead president. I would love to read a book about Warhol written by a Midwestern housewife. As for Andy: “I would rather watch somebody buy their underwear than read a book they wrote.” Until I picked up The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to B and back Again (1975, apparently), it had never occurred to me to peruse the material that the artist ostensibly wrote himself. It made more sense to read Warhol through a filter, like staring into the sun directly would burn and permanently damage me somehow. How much of Warhol’s writing is Warhol’s writing isn’t entirely important. He is the author of this book --- although it was ghostwritten (to whatever extent) by Pat Hackett (credited only as a redactor in the dedication) --- for the same reason he is the artist behind work he didn’t complete himself (or the same reason it doesn’t matter many of his movies are slowed down, for length, and looped instead of filmed totally). Andy Warhol is a novelist who wrote a book, A: a novel, that didn’t require him to write anything --- or do more than hand over a tape recorder to his friends and then employ transcribers. Yet in Philosophy a voice, usually absent or reformatted in other texts, distinctly Warholian, or distinctly anchoring the Warholian within a personal mode of expression, haunts the pages here and there. What does poetry written by a machine sound like? This book contains strings of anecdotes and aphorisms --- suggesting a wit akin to Wilde that A probably didn’t demonstrate socially. (It is hard to conceive of Andy awkwardly creeping around a party before suddenly charming a crowd of socialites with a bon mot, delivered with confidence and ease: “I guess that’s what marriage boils down to --- your wife buys your underwear for you.” A here is more articulate and slyer than in interviews. He defines the paradigm of Andy Warhol, which we all swim around in, with a self-awareness that presupposes many of the regurgitated insights of subsequent scholars and commentators. “I have no memory,” he claims. He taunts us: “I have to look into the mirror for some more clues. Nothing is missing. It’s all there. The affectless gaze. The diffracted grace […] the bored languor, the wasted pallor […] the chic freakiness, the basically passive astonishment, the enthralling secret knowledge […] the chintzy joy, the revelatory tropisms, the chalky puckish mask, the slight Slavic look […] the childlike, gum-chewing naiveté, the glamour rooted in despair, the self-admiring carelessness, the perfected otherness, the wispiness, the shadowy, voyeuristic, vaguely sinister aura, the pale, soft-spoken magical presence, the skin and bones […] the albino-chalk skin. Parchmentlike. Reptilian. Almost blue […] The knobby knees. The roadmap of scars, The long bony arms, so white they look bleached. The arresting hands. The pinhead eyes. The banana ears […] The graying lips. The shaggy, silver-white hair, soft and metallic. The cords of the neck standing out around the big Adam’s apple. It’s all there […] nothing is missing.” This is one of the book’s most flamboyant and decadent set-pieces; Warhol here offers us the gift of his persona, and then becomes it. The ingenious climax of the book --- a giant set-piece consisting of an exhausting rant performed by a friend over the phone, describing upsettingly obsessive cleaning routines she follows to tidy her apartment (naked and on speed) --- reads as contemporary a literary experiment as the noncreative writing of Kenny G and other conceptual poets. It is boring, artful, out of place in context, and weighs down the end of the text. Warhol sits on the phone and listens indifferently, wordlessly setting the receiver down only to occasionally replace the jam he’s eating with another snack. Warhol was probably a good listener. In this particular passage, he disappears into a frustratingly weird narrative of drug-fueled chores. He plays a trick by fading, chameleon-like, into the wallpaper. His friend has to make sure everything is totally sanitized and clean; he lets her wash him out of his own story. I squint, trying to detect the ego, superego, or id floating around within this Warholian matrix. Who would win in a match between A and Freud? Recent documentaries and studies of Warhol tend to sensationalize the ugliness of the man. Maybe the general public doesn’t know A suffered from tragically bad skin, baldness under his lovely wig --- or that he hardly ever enjoyed a fulfilling sex life, had to assemble himself in front of a mirror, with all sorts of pastes and products, before feeling presentable, or that he was scarred and damaged after being shot, having to wear a corset thereafter. Documentarians, filmmakers, and scholars have been trying to dramatically expose this side of Warhol; thus, I assumed it had always been hidden --- that A couldn’t stand such facts of his bodily failures, his monstrosity, incorporated under the public title of Andy Warhol. I was surprised, then, at what A, as author, was forward about when writing about his body in Philosophy. The angst of not being beautiful is typed across page after page. He wakes up and dials a number; into the phone he sighs, “I wake up every morning. I open my eyes and think: here we go again.” He wanted to look into the mirror and see nothing --- because he desired the erasure of his imperfections. He knew he didn’t really belong in the glossy magazines of the celebrities he adored, but he had to find a way to kidnap that glamour. He posits that addressing what he doesn’t like about himself is a way to erase the impact of those undesirable qualities on his life. So right away he is discussing his pimples and, as evidenced in above set-piece, many other examples of the freakish characteristics that plagued and defined him. It could have come off as a joke contemporaneously, but today we read the seriousness, and tragedy, in his comic remark: “I need about an hour to glue myself together.” Applying his artifice was time consuming. The way his wig was pasted or bound to his bald pate must have been painful; the obviousness of his weirdness and the futility to cake it over with make-up and creams must have been wholly embarrassing. Once, at a book signing, a girl grabbed off his wig and disappeared into a getaway car. Exposed, A was terrified; he later claimed that that event was equally traumatizing as being shot in the gut and almost dying. Yet, in retrospect, the details he waltzes around are telling. Although Warhol refers obliquely to his “wings,” I am unclear if that is even a fuzzy reference to his hairpieces. Anyway, in writing he claims that he has “gone gray” by dying his existing hair; he spends plenty of time turning this excuse into a demonstration of his “philosophy.” (Funny that the implicit intent of this book is to outline/codify a Warholian ideology when that concept, as such, was realized only as a mirroring of other cultural surfaces.) Was his “going gray” claim a joke or was Warhol unprepared to announce in print that the radical style of his platinum wigs was defensive in origin, meant to conceal? Before he switched to his trademark wig style, those who knew him were embarrassed for him because of how phony his more naturally colored hairpieces looked. Often, when somebody was mad at Andy, he attacked his appearance. A detail of Warhol’s biography that is contrastively ignored is his drug use --- it was easy for him to refer to taking his “vitamins” and “diet pills,” but those drugs should now be understood as amphetamines, which he was in habitual practice of swallowing (as far as I understand from my own research). The relationship of amphetamine’s grammar to the Warholian construct could benefit from further study. In Philosophy, he mentions taking pills only in passing, innocently refusing to discuss what they mean to him or his work, and he glosses the drug use that characterized his social milieu via playfully opaque euphemisms. When a “poke” (injection of drugs) is mentioned, it is unclear whether heroin or speed is the substance being abused. A also avoids bringing up his queerness, which I find incongruous considering the explicit (plus implicit) themes of queer sexuality in his art. He portrays himself as having monkish dedication to his career and, almost literally, married to his tape recorder (his “wife”); when the subject of romantic or sexual interaction arises he uses the feminine pronoun when referring to his partner. Although Warhol doesn’t seem to be able to fit within the developing model of postwar male homosexuality, he is definitely queer. He had same sex attractions and relationships, however problematic. Maybe Warhol would have made a profound contribution to queer literature had he addressed the subject in this text --- maybe he felt like he couldn’t (or did not want to). Anyway, A can be just about whatever we want; that’s why we love him so. He just can’t be himself --- not if he’s some form of simulacrum. A human subject can only be thought about in these terms abstractly. An agent like you, dear reader, can’t demonstrate yourself as a copy without an original, not in earnest (so I say, at least). That was Warhol’s project, nonetheless. He wanted to cake simulation in suffocating layers over his agency, thus creating the curtain to disappear behind forever. Advice from A: “If you can’t believe it’s happening, pretend it’s a movie.” I write about A all the time and never get any closer to solving anything; that’s the point. I don’t know, as they say. From I Am Happy: Interviewer, “What does human judgment mean to you?” Andy, “Human judgment doesn’t mean anything to me. Human judgment doesn’t exist for technology. I don’t like problems because you have to find a solution. Without judgment there can be no problems. What I try to do is avoid solving problems. Problems are too hard and too many. I don’t think finding solutions really adds up to anything --- it only creates more problems. Becoming a machine is a way of making things easy. And it gives me something to do. I like that.”

1 comment:

Chris: I changed my blog address–theboyinthetree.blogspot.com. Also, you should check out Richard Foreman's work if you haven't already. K. just turned me onto him; reminded me of you.

What's the date for the forthcoming issue of Corr.?

Post a Comment