The CORRESPONDING SOCIETY hereby invites you to come celebrate with us the launch of a brand new literary venture! The “Know No” chapbook series, months in the making, was curated by Robert Snyderman and designed by art directors Caroline Gormley and Sonia Farmer. The collection includes the following three distinct and exciting texts:

“Elegies for A.R. Ammons” by David Swensen

“Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land?” by Lonely Christopher

“This Pose Can Be Held for Only So Long” by Caroline Gormley

Please join us on 3 September (7pm), at local waterhole (caffeinated/alcoholic) Outpost, for an evening of revelry, libations, and poetry. Plus the chance to win fabulous prizes! Readers will include David Swensen, Lonely Christopher, and Adrian Shirk (satalite-reading for Ms. Gormley, who lives in Austin, Texas).

Venue: Outpost Lounge

Location: 1014 Fulton St (Brooklyn)

Date: 3 September

Time: 7pm

Featured Readers: David Swensen, Lonely Christopher, Adrian Shirk

Saturday, August 29, 2009

Saturday, August 22, 2009

Straight Proust

Shelf Space

On Qualities and Locations of Queer Literature

by Lonely Christopher

What is queer literature? I think this is an important question and a stupid one. In the “gay fiction/non-fiction shelves at Barnes and Noble” sense, “gay lit” is a minoritizing concept. I have never plucked a title off the “gay fiction” shelf; to do so seems unfortunately tacky (considering my snobby bias re the quality of writing that is typically relegated there, possibly correlative to chick lit). About the only text I’ve taken home from the “gay non-fiction” shelf is Epistemology of the Closet. In that book, Sedgwick discusses “the contradictions […] internal to all the important twentieth-century understandings of homo/heterosexual definition,” which include “the contradiction between seeing homo/heterosexual definition on the one hand as an issue of active importance primarily for a small, distinct, relatively fixed homosexual minority […] and seeing it on the other hand as an issue of continuing, determinative importance in the lives of people across the spectrum of sexualities[.]” But, of course, we have all read Epistemology of the Closet --- which is why I find it so queer the issue of themes of non-normative sexuality in creative writing is treated with a minoritizing disdain, in casual conversation, by my closest friends. I am not arguing against the organization of texts by subject --- without which Mr. Dewey weeps and I get confused at the library --- but it’s undeniable that a social stigma is attached to what is essentially the ghettoization of queer writing. Notably, reputable queer authors do not usually languish in the “gay fiction” section: you’ll probably find City of Night and the oeuvre of Burroughs in regular literature. Although the pessimistic view might be that those guys became institutionalized enough to receive honorary-straight status, which comes with admission to the grown-ups table; just as reasonable, and more positively, it might also be that important literature is important literature. We’d love to claim the latter the case here in our progressive day. So why is it, then, that certain of my peers continually express concern that I am running the risk, in foregrounding queer themes in my own work, of losing their interest by esoterically going gay? I posit the answer relates to a kind of latent homophobia that’s ubiquitous in contemporary literary discourse. Despite familiarity with all the trendy texts of queer theory --- Sedgwick, Butler, Foucault --- straight-identified writers and readers (that I know) can’t help finding queer material in literature kind of boring and gross. Although I don’t feel comfortable organizing myself under the cultural rubric of the “gay” construct, my non-normative sexual identity (or: queerness) still came with implicit subscription to a rich and fascinating gay canon of creative texts and critical perspectives. My interest in certain dimensions of art and theory (that is, the gay dimensions) presupposes my access to queer tradition. I had to struggle out of a stuffy heteronormativity before I learned to love queer culture. This is the result of the minoritizing influence built in to normative discourse, which sets apart anything articulating a strong queer perspective. (Such values also make you straight until proven otherwise, so many queer boys and girls tend to be raised straight, which retards them culturally.) I mean to say: queerness isn’t implicitly just for gays, but cultural hegemony ignores this and enforces ghettoization. So friends squirm when my writing swerves into fag land. Most of what I’ve been doing for about a year results from a project of queer investigation. Previously, the attention of my creative writing has been more scattered. When peers began to notice the unfamiliar direction my work was heading in, the reaction was almost unanimously suspicious (turning negative). There was an audience for my chamber drama Gay Play when I staged it last year --- but when I wrote a sequel, kids started worrying. When I ended up with Gay Play 3, some reactions were outright hostile: I was turning into a “scene queen.” The primary response I’ve been getting is that I shouldn’t write about queer themes all the time because that runs of risk of making me a “special interest” writer. A friend recently complained over the intellectual poverty of art about same sex relationships; I pointed out my unpublished novel focuses on a straight married couple. He said, correction, he didn’t like any art about romantic relationships --- we went home and watched a Woody Allen movie, which we enjoyed. That is an irony of straight discomfort with queer lit --- it doesn’t go both ways: queers don’t seem to have much of a problem with appreciating all the fine heterocentric art in the world. In fact, I quite love Woody Allen, for example, even though I do not relate at all to his hetero treatment of love and sex. Weirdly, a whole bunch (most?) of the heroes of the normative canon, which have become the favorites of my straight peers, are total homos. I have another friend who used to really want to erase that unfortunate detail. When we were young we were crazy about Rimbaud. Despite the whole Verlaine fling --- which, you know, gave us some pretty good poetry --- and the evidence Arthur had a kept boy when he quit the writing game for business, according to this friend Rimbaud wasn’t “technically gay” because he doesn’t fit neatly under the contemporary gay construct; thus, his sexuality is unimportant in the consideration of his work. Next came Proust, which my friend tried to prove was actually straight because he wrote so well about heterosexual relationships and penned a few flowery letters to his women friends. Never mind, you know, the overwhelmingly queer bent of In Search of Lost Time or any of his fancy gay love. It went on like that --- I think Whitman came next --- although this fellow is very intelligent and his attitude might be different now. I think Sedgwick makes an important case for reading literature from a queer perspective, which is a practice often considered useless, extraneous folly by even those straights who’ve read Sedgwick. When arguing defensively against the validity of queer perspectives in art, my straight friends often resort to a few stances exampled in Epistemology of the Closet. The list of possible attacks is sort of lengthy, but it’s worth representing here in full: “1. Passionate language of same-sex attraction was extremely common during whatever period is under discussion --- and therefore must have been completely meaningless. Or 2. Same-sex genital relations may have been perfectly common during the period under discussion --- but since there was no language about them, they must have been completely meaningless. Or 3. Attitudes about homosexuality were intolerant back then, unlike now --- so people probably didn’t do anything. Or 4. Prohibitions against homosexuality didn’t exist back then, unlike now --- so if people did anything, it was completely meaningless. Or 5. The word 'homosexuality' wasn’t coined until 1869 --- so everyone before then was heterosexual. (Of course, heterosexuality has always existed.) Or 6. The author under discussion is certified or rumored to have had an attachment to someone of the other sex --- so their feelings about people of their own sex must have been completely meaningless. Or (under perhaps somewhat different rules of admissible evidence) 7. There is no actual proof of homosexuality, such as sperm taken from the body of another man or a nude photograph with another woman --- so the author may be assumed to have been ardently and exclusively heterosexual. Or (as a last resort) 8. The author or the author’s important attachments may very well have been homosexual --- but it would be provincial to let so insignificant a fact make any difference at all to our understanding of any serious project of life, writing, or thought.” To Sedgwick, this puritanical outrage at the canon being reconfigured along queer lines evinces, beyond sheer homophobia, a hegemonic ignorance necessary in sustaining the established order: “Don’t ask; You shouldn’t know.” There is the additional fallacy of misunderstanding the divisions between popular and literary writing when it comes to queer texts (like mine). My treatment of queer themes, its centrality in my recent work, gets conflated by friends with the production of the low paperbacks shoved out of the literary discourse to languish on the dusty “gay fiction” shelf. Thus, writing about queerness at all is the same thing as writing for the supposedly non-critical popular gay audience (and we know they don’t even read, pity). The situation is probably a little different right now in China, where the first two Gay Plays are being published and staged. The communal homophobia doesn’t seem to have been internalized and caked over with organized defenses there as it has here stateside. When casting the English production of Gay Play 2, I’m told it was impossible to convince noncitizens (expatriates and the like) living locally to participate because of the social fear that, I guess, ultimately implies the punishment of deportation for subversive activities. In climates of more direct sociopolitical repression, any conception of queer literature is disallowed from validation or even existence; in cultures of internalized homophobia the dominant critical discourse substitutes in the government’s role in authoritarian censorship. When it comes to the troublesome attitudes of my friends here in the US, I think I should make an important distinction clear because it’s probably not terribly considered from a straight perspective. Straight writers focus on themes of sexuality frequently and sans compunction --- this is because sexuality is fascinating and complex. A straight-identified writer has implicit access to her life of experiences parsing the complications of sexuality from her own vantage. This fundamental catalog of conceptualized sexuality is obviously available to the gay or queer-identified writer as well. There’s something else, though, that influences the queer writer, problematizing and inspiring his work: his subjugated position in a heteronormative social grammar. There is no aspect of the queer subject that’s structurally inherent (thereby inalienable) in our literary or social formations. This is evidenced in how a queer writerly focus is so easily suspect: there is no right to a gay literature within the intellectual framework we operate in as artists. A straight writer writing straight work writes literature; a queer writer writing queer work writes queer literature, which doesn’t exist. Maybe, to restart, the question is, rather: What should queer literature be? Does it belong outside the normative canon, within it qua subspecies, or should there even be a designation distinct for it at all? I know the gay canon did form outside normative discourse --- it had to because of where its subscribers were: the institution of the closet. I suppose I’d like to see something suggested by the “universalizing view” identified in Sedgwick: a queer literature different from the established and ghettoized gay canon, something that’s not as minoritized but in active conversation with our normative canon. When somebody picks up a volume of Proust from the “literature” shelf, for example, she understands the text simultaneously as a great novel and a great queer novel. I like the duality there. A critical engagement with queerness in treatments of literature is undeniably important --- not only from a gay perspective, or from wherever I’m located personally, but for all writers and readers of creative texts (that’s us). Queer has value. As Annamarie Jagose writes, “Queer is not outside the magnetic field of identity. Like some postmodern architecture, it turns identity inside out, and displays its supports exoskeletally."

On Qualities and Locations of Queer Literature

by Lonely Christopher

What is queer literature? I think this is an important question and a stupid one. In the “gay fiction/non-fiction shelves at Barnes and Noble” sense, “gay lit” is a minoritizing concept. I have never plucked a title off the “gay fiction” shelf; to do so seems unfortunately tacky (considering my snobby bias re the quality of writing that is typically relegated there, possibly correlative to chick lit). About the only text I’ve taken home from the “gay non-fiction” shelf is Epistemology of the Closet. In that book, Sedgwick discusses “the contradictions […] internal to all the important twentieth-century understandings of homo/heterosexual definition,” which include “the contradiction between seeing homo/heterosexual definition on the one hand as an issue of active importance primarily for a small, distinct, relatively fixed homosexual minority […] and seeing it on the other hand as an issue of continuing, determinative importance in the lives of people across the spectrum of sexualities[.]” But, of course, we have all read Epistemology of the Closet --- which is why I find it so queer the issue of themes of non-normative sexuality in creative writing is treated with a minoritizing disdain, in casual conversation, by my closest friends. I am not arguing against the organization of texts by subject --- without which Mr. Dewey weeps and I get confused at the library --- but it’s undeniable that a social stigma is attached to what is essentially the ghettoization of queer writing. Notably, reputable queer authors do not usually languish in the “gay fiction” section: you’ll probably find City of Night and the oeuvre of Burroughs in regular literature. Although the pessimistic view might be that those guys became institutionalized enough to receive honorary-straight status, which comes with admission to the grown-ups table; just as reasonable, and more positively, it might also be that important literature is important literature. We’d love to claim the latter the case here in our progressive day. So why is it, then, that certain of my peers continually express concern that I am running the risk, in foregrounding queer themes in my own work, of losing their interest by esoterically going gay? I posit the answer relates to a kind of latent homophobia that’s ubiquitous in contemporary literary discourse. Despite familiarity with all the trendy texts of queer theory --- Sedgwick, Butler, Foucault --- straight-identified writers and readers (that I know) can’t help finding queer material in literature kind of boring and gross. Although I don’t feel comfortable organizing myself under the cultural rubric of the “gay” construct, my non-normative sexual identity (or: queerness) still came with implicit subscription to a rich and fascinating gay canon of creative texts and critical perspectives. My interest in certain dimensions of art and theory (that is, the gay dimensions) presupposes my access to queer tradition. I had to struggle out of a stuffy heteronormativity before I learned to love queer culture. This is the result of the minoritizing influence built in to normative discourse, which sets apart anything articulating a strong queer perspective. (Such values also make you straight until proven otherwise, so many queer boys and girls tend to be raised straight, which retards them culturally.) I mean to say: queerness isn’t implicitly just for gays, but cultural hegemony ignores this and enforces ghettoization. So friends squirm when my writing swerves into fag land. Most of what I’ve been doing for about a year results from a project of queer investigation. Previously, the attention of my creative writing has been more scattered. When peers began to notice the unfamiliar direction my work was heading in, the reaction was almost unanimously suspicious (turning negative). There was an audience for my chamber drama Gay Play when I staged it last year --- but when I wrote a sequel, kids started worrying. When I ended up with Gay Play 3, some reactions were outright hostile: I was turning into a “scene queen.” The primary response I’ve been getting is that I shouldn’t write about queer themes all the time because that runs of risk of making me a “special interest” writer. A friend recently complained over the intellectual poverty of art about same sex relationships; I pointed out my unpublished novel focuses on a straight married couple. He said, correction, he didn’t like any art about romantic relationships --- we went home and watched a Woody Allen movie, which we enjoyed. That is an irony of straight discomfort with queer lit --- it doesn’t go both ways: queers don’t seem to have much of a problem with appreciating all the fine heterocentric art in the world. In fact, I quite love Woody Allen, for example, even though I do not relate at all to his hetero treatment of love and sex. Weirdly, a whole bunch (most?) of the heroes of the normative canon, which have become the favorites of my straight peers, are total homos. I have another friend who used to really want to erase that unfortunate detail. When we were young we were crazy about Rimbaud. Despite the whole Verlaine fling --- which, you know, gave us some pretty good poetry --- and the evidence Arthur had a kept boy when he quit the writing game for business, according to this friend Rimbaud wasn’t “technically gay” because he doesn’t fit neatly under the contemporary gay construct; thus, his sexuality is unimportant in the consideration of his work. Next came Proust, which my friend tried to prove was actually straight because he wrote so well about heterosexual relationships and penned a few flowery letters to his women friends. Never mind, you know, the overwhelmingly queer bent of In Search of Lost Time or any of his fancy gay love. It went on like that --- I think Whitman came next --- although this fellow is very intelligent and his attitude might be different now. I think Sedgwick makes an important case for reading literature from a queer perspective, which is a practice often considered useless, extraneous folly by even those straights who’ve read Sedgwick. When arguing defensively against the validity of queer perspectives in art, my straight friends often resort to a few stances exampled in Epistemology of the Closet. The list of possible attacks is sort of lengthy, but it’s worth representing here in full: “1. Passionate language of same-sex attraction was extremely common during whatever period is under discussion --- and therefore must have been completely meaningless. Or 2. Same-sex genital relations may have been perfectly common during the period under discussion --- but since there was no language about them, they must have been completely meaningless. Or 3. Attitudes about homosexuality were intolerant back then, unlike now --- so people probably didn’t do anything. Or 4. Prohibitions against homosexuality didn’t exist back then, unlike now --- so if people did anything, it was completely meaningless. Or 5. The word 'homosexuality' wasn’t coined until 1869 --- so everyone before then was heterosexual. (Of course, heterosexuality has always existed.) Or 6. The author under discussion is certified or rumored to have had an attachment to someone of the other sex --- so their feelings about people of their own sex must have been completely meaningless. Or (under perhaps somewhat different rules of admissible evidence) 7. There is no actual proof of homosexuality, such as sperm taken from the body of another man or a nude photograph with another woman --- so the author may be assumed to have been ardently and exclusively heterosexual. Or (as a last resort) 8. The author or the author’s important attachments may very well have been homosexual --- but it would be provincial to let so insignificant a fact make any difference at all to our understanding of any serious project of life, writing, or thought.” To Sedgwick, this puritanical outrage at the canon being reconfigured along queer lines evinces, beyond sheer homophobia, a hegemonic ignorance necessary in sustaining the established order: “Don’t ask; You shouldn’t know.” There is the additional fallacy of misunderstanding the divisions between popular and literary writing when it comes to queer texts (like mine). My treatment of queer themes, its centrality in my recent work, gets conflated by friends with the production of the low paperbacks shoved out of the literary discourse to languish on the dusty “gay fiction” shelf. Thus, writing about queerness at all is the same thing as writing for the supposedly non-critical popular gay audience (and we know they don’t even read, pity). The situation is probably a little different right now in China, where the first two Gay Plays are being published and staged. The communal homophobia doesn’t seem to have been internalized and caked over with organized defenses there as it has here stateside. When casting the English production of Gay Play 2, I’m told it was impossible to convince noncitizens (expatriates and the like) living locally to participate because of the social fear that, I guess, ultimately implies the punishment of deportation for subversive activities. In climates of more direct sociopolitical repression, any conception of queer literature is disallowed from validation or even existence; in cultures of internalized homophobia the dominant critical discourse substitutes in the government’s role in authoritarian censorship. When it comes to the troublesome attitudes of my friends here in the US, I think I should make an important distinction clear because it’s probably not terribly considered from a straight perspective. Straight writers focus on themes of sexuality frequently and sans compunction --- this is because sexuality is fascinating and complex. A straight-identified writer has implicit access to her life of experiences parsing the complications of sexuality from her own vantage. This fundamental catalog of conceptualized sexuality is obviously available to the gay or queer-identified writer as well. There’s something else, though, that influences the queer writer, problematizing and inspiring his work: his subjugated position in a heteronormative social grammar. There is no aspect of the queer subject that’s structurally inherent (thereby inalienable) in our literary or social formations. This is evidenced in how a queer writerly focus is so easily suspect: there is no right to a gay literature within the intellectual framework we operate in as artists. A straight writer writing straight work writes literature; a queer writer writing queer work writes queer literature, which doesn’t exist. Maybe, to restart, the question is, rather: What should queer literature be? Does it belong outside the normative canon, within it qua subspecies, or should there even be a designation distinct for it at all? I know the gay canon did form outside normative discourse --- it had to because of where its subscribers were: the institution of the closet. I suppose I’d like to see something suggested by the “universalizing view” identified in Sedgwick: a queer literature different from the established and ghettoized gay canon, something that’s not as minoritized but in active conversation with our normative canon. When somebody picks up a volume of Proust from the “literature” shelf, for example, she understands the text simultaneously as a great novel and a great queer novel. I like the duality there. A critical engagement with queerness in treatments of literature is undeniably important --- not only from a gay perspective, or from wherever I’m located personally, but for all writers and readers of creative texts (that’s us). Queer has value. As Annamarie Jagose writes, “Queer is not outside the magnetic field of identity. Like some postmodern architecture, it turns identity inside out, and displays its supports exoskeletally."

Monday, August 10, 2009

Upstate Reading

If, for whatever reason, you happen to be upstate, or in the mood to travel upstate, this week, please note that some of us of the Corresponding Society are in the same position (for we have a reading). Also note that our chapbooks will be ready and available for the first time that day. Details:

Venue: the Dragonfly Café

Location: 7 Wheeler Ave, Pleasantville, NY

Date: Thurs, August 13

Time: 7pm

Featured Readers: Christopher Sweeney, Adrian Shirk, Lonely Christopher, David Swensen

Venue: the Dragonfly Café

Location: 7 Wheeler Ave, Pleasantville, NY

Date: Thurs, August 13

Time: 7pm

Featured Readers: Christopher Sweeney, Adrian Shirk, Lonely Christopher, David Swensen

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

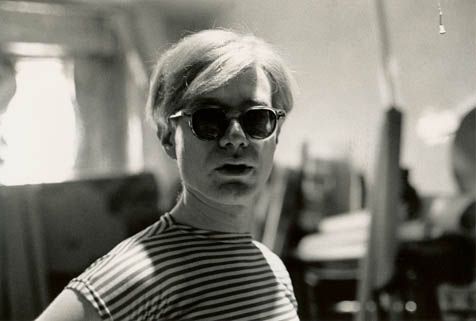

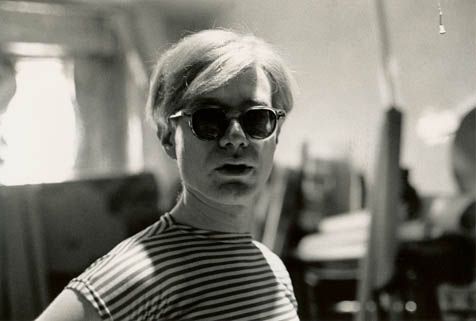

All Warhol

A: a Problem

Warhol Speaks for Himself, Kinda

by Lonely Christopher

Andy Warhol is intellectual property to which we all share the copyright. After staging a play about Andy Warhol in a rural Pennsylvanian town, the local audience approached me with about the same ideas on the subject as articulated by anyone I’ve talked to about it within academia or bohemia. “Andy Warhol’s whole life wassis work, ya’know, so he became some sorta performance, an anti-human er anti-artist, like he turned everything he saw inta art so it done mean nothin. He took th’ image an emptied it all out, so it were just all on th’ surface. Like, he didn’t see no depth in nothin’ --- so his art was turnin’ everything inta culture, inta an empty signifier, doncha know. I’d say, shucks, Warhol has gone the furthest in the annihilation of th’ artistic and th’ creative act; he was uh simulacrum.” Andy Warhol is as egalitarian as Coca-Cola, a soft drink that he appreciated because its popularity meant some bum on the street drank exactly the same Coke as Elizabeth Taylor. Warhol is an American invention. Andy: “That could be […] the best American invention --- to be able to disappear.” A has disappeared into complete ubiquity. We talk about Warhol and mean nothing. I chewed up Baudrillard’s essay on Andy (“Machinic Snobbery,” from The Perfect Crime) and collaged its pulpy guts into my play, along with sources like Kenny Goldsmith’s edition of A’s selected interviews. I interviewed Kenneth once and we talked some about Warhol. LC: “How does that work? When I first started thinking about Warhol I was thinking about him actually in relation to the Situationists because I was studying the Situationists and I saw that they wanted to effect change but they designed their movement in a way where all their ideas were easily colonized and they really quickly failed. That failure made me think of Warhol because he seemed to have designed his work and life in a way where whatever the position it was put in it still retained its integrity.” KG: “You’re very astute; that’s a great point. But the real thing is that the secret of Warhol was he never intended resistance and therefore something that could never offer resistance could never be co-opted. That’s fucking brilliant. He was completely complicit and by being complicit he was subversive. It was a very brilliant strategy of his. He took a lot of shit for it, too. People didn’t understand.” My play, I Am Happy, is about a major problematic in studying Warhol: the man/machine dichotomy, which seems to be unresolved. The premise: an interviewer questions A, vomiting about the artist qua sign system before doubling back and suspiciously interrogating that position (receiving only vaguely bored and clever answers from his subject). He sits frustrated over A (who pushes pills across the surface of a mirror); frowns: “A lot of people are inclined to put you down because you operate at a certain distance --- mechanically, artificially. And yet it is claimed you are not, cannot be, truly a mutant. You are made of the same material as everyone else, you are not yourself a mirror or a machine --- but regular blood and guts (violence being your threatened reminder, ugliness your secret humiliation). Doesn’t this problematize addressing you as some sort of text, sign system, or an object? […] Is [your] mechanic affectation rather an adaptive mythopoetics?” A says, as usual, “I don’t know.” Upon studying Kenny’s collection of documents for the first time, the actual interviews, I learned a valuable lesson re the importance of not knowing (even if you do). I like reading theorists, biographers, and memoirists inscribing Warhol for themselves (and us) in various texts. Baudrillard denies biography, or the very embodiment of the idea of Warhol; Koestenbaum (in a monograph for Penguin) attempts to invoke a tortured and imaginative sexuality for his subject; Coacello often uses Warhol to define and validate his own narrative (Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up); Bockris (The Life and Death of Andy Warhol) constructs A as the classic biographer’s subject, portraying him historically like a dead president. I would love to read a book about Warhol written by a Midwestern housewife. As for Andy: “I would rather watch somebody buy their underwear than read a book they wrote.” Until I picked up The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to B and back Again (1975, apparently), it had never occurred to me to peruse the material that the artist ostensibly wrote himself. It made more sense to read Warhol through a filter, like staring into the sun directly would burn and permanently damage me somehow. How much of Warhol’s writing is Warhol’s writing isn’t entirely important. He is the author of this book --- although it was ghostwritten (to whatever extent) by Pat Hackett (credited only as a redactor in the dedication) --- for the same reason he is the artist behind work he didn’t complete himself (or the same reason it doesn’t matter many of his movies are slowed down, for length, and looped instead of filmed totally). Andy Warhol is a novelist who wrote a book, A: a novel, that didn’t require him to write anything --- or do more than hand over a tape recorder to his friends and then employ transcribers. Yet in Philosophy a voice, usually absent or reformatted in other texts, distinctly Warholian, or distinctly anchoring the Warholian within a personal mode of expression, haunts the pages here and there. What does poetry written by a machine sound like? This book contains strings of anecdotes and aphorisms --- suggesting a wit akin to Wilde that A probably didn’t demonstrate socially. (It is hard to conceive of Andy awkwardly creeping around a party before suddenly charming a crowd of socialites with a bon mot, delivered with confidence and ease: “I guess that’s what marriage boils down to --- your wife buys your underwear for you.” A here is more articulate and slyer than in interviews. He defines the paradigm of Andy Warhol, which we all swim around in, with a self-awareness that presupposes many of the regurgitated insights of subsequent scholars and commentators. “I have no memory,” he claims. He taunts us: “I have to look into the mirror for some more clues. Nothing is missing. It’s all there. The affectless gaze. The diffracted grace […] the bored languor, the wasted pallor […] the chic freakiness, the basically passive astonishment, the enthralling secret knowledge […] the chintzy joy, the revelatory tropisms, the chalky puckish mask, the slight Slavic look […] the childlike, gum-chewing naiveté, the glamour rooted in despair, the self-admiring carelessness, the perfected otherness, the wispiness, the shadowy, voyeuristic, vaguely sinister aura, the pale, soft-spoken magical presence, the skin and bones […] the albino-chalk skin. Parchmentlike. Reptilian. Almost blue […] The knobby knees. The roadmap of scars, The long bony arms, so white they look bleached. The arresting hands. The pinhead eyes. The banana ears […] The graying lips. The shaggy, silver-white hair, soft and metallic. The cords of the neck standing out around the big Adam’s apple. It’s all there […] nothing is missing.” This is one of the book’s most flamboyant and decadent set-pieces; Warhol here offers us the gift of his persona, and then becomes it. The ingenious climax of the book --- a giant set-piece consisting of an exhausting rant performed by a friend over the phone, describing upsettingly obsessive cleaning routines she follows to tidy her apartment (naked and on speed) --- reads as contemporary a literary experiment as the noncreative writing of Kenny G and other conceptual poets. It is boring, artful, out of place in context, and weighs down the end of the text. Warhol sits on the phone and listens indifferently, wordlessly setting the receiver down only to occasionally replace the jam he’s eating with another snack. Warhol was probably a good listener. In this particular passage, he disappears into a frustratingly weird narrative of drug-fueled chores. He plays a trick by fading, chameleon-like, into the wallpaper. His friend has to make sure everything is totally sanitized and clean; he lets her wash him out of his own story. I squint, trying to detect the ego, superego, or id floating around within this Warholian matrix. Who would win in a match between A and Freud? Recent documentaries and studies of Warhol tend to sensationalize the ugliness of the man. Maybe the general public doesn’t know A suffered from tragically bad skin, baldness under his lovely wig --- or that he hardly ever enjoyed a fulfilling sex life, had to assemble himself in front of a mirror, with all sorts of pastes and products, before feeling presentable, or that he was scarred and damaged after being shot, having to wear a corset thereafter. Documentarians, filmmakers, and scholars have been trying to dramatically expose this side of Warhol; thus, I assumed it had always been hidden --- that A couldn’t stand such facts of his bodily failures, his monstrosity, incorporated under the public title of Andy Warhol. I was surprised, then, at what A, as author, was forward about when writing about his body in Philosophy. The angst of not being beautiful is typed across page after page. He wakes up and dials a number; into the phone he sighs, “I wake up every morning. I open my eyes and think: here we go again.” He wanted to look into the mirror and see nothing --- because he desired the erasure of his imperfections. He knew he didn’t really belong in the glossy magazines of the celebrities he adored, but he had to find a way to kidnap that glamour. He posits that addressing what he doesn’t like about himself is a way to erase the impact of those undesirable qualities on his life. So right away he is discussing his pimples and, as evidenced in above set-piece, many other examples of the freakish characteristics that plagued and defined him. It could have come off as a joke contemporaneously, but today we read the seriousness, and tragedy, in his comic remark: “I need about an hour to glue myself together.” Applying his artifice was time consuming. The way his wig was pasted or bound to his bald pate must have been painful; the obviousness of his weirdness and the futility to cake it over with make-up and creams must have been wholly embarrassing. Once, at a book signing, a girl grabbed off his wig and disappeared into a getaway car. Exposed, A was terrified; he later claimed that that event was equally traumatizing as being shot in the gut and almost dying. Yet, in retrospect, the details he waltzes around are telling. Although Warhol refers obliquely to his “wings,” I am unclear if that is even a fuzzy reference to his hairpieces. Anyway, in writing he claims that he has “gone gray” by dying his existing hair; he spends plenty of time turning this excuse into a demonstration of his “philosophy.” (Funny that the implicit intent of this book is to outline/codify a Warholian ideology when that concept, as such, was realized only as a mirroring of other cultural surfaces.) Was his “going gray” claim a joke or was Warhol unprepared to announce in print that the radical style of his platinum wigs was defensive in origin, meant to conceal? Before he switched to his trademark wig style, those who knew him were embarrassed for him because of how phony his more naturally colored hairpieces looked. Often, when somebody was mad at Andy, he attacked his appearance. A detail of Warhol’s biography that is contrastively ignored is his drug use --- it was easy for him to refer to taking his “vitamins” and “diet pills,” but those drugs should now be understood as amphetamines, which he was in habitual practice of swallowing (as far as I understand from my own research). The relationship of amphetamine’s grammar to the Warholian construct could benefit from further study. In Philosophy, he mentions taking pills only in passing, innocently refusing to discuss what they mean to him or his work, and he glosses the drug use that characterized his social milieu via playfully opaque euphemisms. When a “poke” (injection of drugs) is mentioned, it is unclear whether heroin or speed is the substance being abused. A also avoids bringing up his queerness, which I find incongruous considering the explicit (plus implicit) themes of queer sexuality in his art. He portrays himself as having monkish dedication to his career and, almost literally, married to his tape recorder (his “wife”); when the subject of romantic or sexual interaction arises he uses the feminine pronoun when referring to his partner. Although Warhol doesn’t seem to be able to fit within the developing model of postwar male homosexuality, he is definitely queer. He had same sex attractions and relationships, however problematic. Maybe Warhol would have made a profound contribution to queer literature had he addressed the subject in this text --- maybe he felt like he couldn’t (or did not want to). Anyway, A can be just about whatever we want; that’s why we love him so. He just can’t be himself --- not if he’s some form of simulacrum. A human subject can only be thought about in these terms abstractly. An agent like you, dear reader, can’t demonstrate yourself as a copy without an original, not in earnest (so I say, at least). That was Warhol’s project, nonetheless. He wanted to cake simulation in suffocating layers over his agency, thus creating the curtain to disappear behind forever. Advice from A: “If you can’t believe it’s happening, pretend it’s a movie.” I write about A all the time and never get any closer to solving anything; that’s the point. I don’t know, as they say. From I Am Happy: Interviewer, “What does human judgment mean to you?” Andy, “Human judgment doesn’t mean anything to me. Human judgment doesn’t exist for technology. I don’t like problems because you have to find a solution. Without judgment there can be no problems. What I try to do is avoid solving problems. Problems are too hard and too many. I don’t think finding solutions really adds up to anything --- it only creates more problems. Becoming a machine is a way of making things easy. And it gives me something to do. I like that.”

Warhol Speaks for Himself, Kinda

by Lonely Christopher

Andy Warhol is intellectual property to which we all share the copyright. After staging a play about Andy Warhol in a rural Pennsylvanian town, the local audience approached me with about the same ideas on the subject as articulated by anyone I’ve talked to about it within academia or bohemia. “Andy Warhol’s whole life wassis work, ya’know, so he became some sorta performance, an anti-human er anti-artist, like he turned everything he saw inta art so it done mean nothin. He took th’ image an emptied it all out, so it were just all on th’ surface. Like, he didn’t see no depth in nothin’ --- so his art was turnin’ everything inta culture, inta an empty signifier, doncha know. I’d say, shucks, Warhol has gone the furthest in the annihilation of th’ artistic and th’ creative act; he was uh simulacrum.” Andy Warhol is as egalitarian as Coca-Cola, a soft drink that he appreciated because its popularity meant some bum on the street drank exactly the same Coke as Elizabeth Taylor. Warhol is an American invention. Andy: “That could be […] the best American invention --- to be able to disappear.” A has disappeared into complete ubiquity. We talk about Warhol and mean nothing. I chewed up Baudrillard’s essay on Andy (“Machinic Snobbery,” from The Perfect Crime) and collaged its pulpy guts into my play, along with sources like Kenny Goldsmith’s edition of A’s selected interviews. I interviewed Kenneth once and we talked some about Warhol. LC: “How does that work? When I first started thinking about Warhol I was thinking about him actually in relation to the Situationists because I was studying the Situationists and I saw that they wanted to effect change but they designed their movement in a way where all their ideas were easily colonized and they really quickly failed. That failure made me think of Warhol because he seemed to have designed his work and life in a way where whatever the position it was put in it still retained its integrity.” KG: “You’re very astute; that’s a great point. But the real thing is that the secret of Warhol was he never intended resistance and therefore something that could never offer resistance could never be co-opted. That’s fucking brilliant. He was completely complicit and by being complicit he was subversive. It was a very brilliant strategy of his. He took a lot of shit for it, too. People didn’t understand.” My play, I Am Happy, is about a major problematic in studying Warhol: the man/machine dichotomy, which seems to be unresolved. The premise: an interviewer questions A, vomiting about the artist qua sign system before doubling back and suspiciously interrogating that position (receiving only vaguely bored and clever answers from his subject). He sits frustrated over A (who pushes pills across the surface of a mirror); frowns: “A lot of people are inclined to put you down because you operate at a certain distance --- mechanically, artificially. And yet it is claimed you are not, cannot be, truly a mutant. You are made of the same material as everyone else, you are not yourself a mirror or a machine --- but regular blood and guts (violence being your threatened reminder, ugliness your secret humiliation). Doesn’t this problematize addressing you as some sort of text, sign system, or an object? […] Is [your] mechanic affectation rather an adaptive mythopoetics?” A says, as usual, “I don’t know.” Upon studying Kenny’s collection of documents for the first time, the actual interviews, I learned a valuable lesson re the importance of not knowing (even if you do). I like reading theorists, biographers, and memoirists inscribing Warhol for themselves (and us) in various texts. Baudrillard denies biography, or the very embodiment of the idea of Warhol; Koestenbaum (in a monograph for Penguin) attempts to invoke a tortured and imaginative sexuality for his subject; Coacello often uses Warhol to define and validate his own narrative (Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up); Bockris (The Life and Death of Andy Warhol) constructs A as the classic biographer’s subject, portraying him historically like a dead president. I would love to read a book about Warhol written by a Midwestern housewife. As for Andy: “I would rather watch somebody buy their underwear than read a book they wrote.” Until I picked up The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to B and back Again (1975, apparently), it had never occurred to me to peruse the material that the artist ostensibly wrote himself. It made more sense to read Warhol through a filter, like staring into the sun directly would burn and permanently damage me somehow. How much of Warhol’s writing is Warhol’s writing isn’t entirely important. He is the author of this book --- although it was ghostwritten (to whatever extent) by Pat Hackett (credited only as a redactor in the dedication) --- for the same reason he is the artist behind work he didn’t complete himself (or the same reason it doesn’t matter many of his movies are slowed down, for length, and looped instead of filmed totally). Andy Warhol is a novelist who wrote a book, A: a novel, that didn’t require him to write anything --- or do more than hand over a tape recorder to his friends and then employ transcribers. Yet in Philosophy a voice, usually absent or reformatted in other texts, distinctly Warholian, or distinctly anchoring the Warholian within a personal mode of expression, haunts the pages here and there. What does poetry written by a machine sound like? This book contains strings of anecdotes and aphorisms --- suggesting a wit akin to Wilde that A probably didn’t demonstrate socially. (It is hard to conceive of Andy awkwardly creeping around a party before suddenly charming a crowd of socialites with a bon mot, delivered with confidence and ease: “I guess that’s what marriage boils down to --- your wife buys your underwear for you.” A here is more articulate and slyer than in interviews. He defines the paradigm of Andy Warhol, which we all swim around in, with a self-awareness that presupposes many of the regurgitated insights of subsequent scholars and commentators. “I have no memory,” he claims. He taunts us: “I have to look into the mirror for some more clues. Nothing is missing. It’s all there. The affectless gaze. The diffracted grace […] the bored languor, the wasted pallor […] the chic freakiness, the basically passive astonishment, the enthralling secret knowledge […] the chintzy joy, the revelatory tropisms, the chalky puckish mask, the slight Slavic look […] the childlike, gum-chewing naiveté, the glamour rooted in despair, the self-admiring carelessness, the perfected otherness, the wispiness, the shadowy, voyeuristic, vaguely sinister aura, the pale, soft-spoken magical presence, the skin and bones […] the albino-chalk skin. Parchmentlike. Reptilian. Almost blue […] The knobby knees. The roadmap of scars, The long bony arms, so white they look bleached. The arresting hands. The pinhead eyes. The banana ears […] The graying lips. The shaggy, silver-white hair, soft and metallic. The cords of the neck standing out around the big Adam’s apple. It’s all there […] nothing is missing.” This is one of the book’s most flamboyant and decadent set-pieces; Warhol here offers us the gift of his persona, and then becomes it. The ingenious climax of the book --- a giant set-piece consisting of an exhausting rant performed by a friend over the phone, describing upsettingly obsessive cleaning routines she follows to tidy her apartment (naked and on speed) --- reads as contemporary a literary experiment as the noncreative writing of Kenny G and other conceptual poets. It is boring, artful, out of place in context, and weighs down the end of the text. Warhol sits on the phone and listens indifferently, wordlessly setting the receiver down only to occasionally replace the jam he’s eating with another snack. Warhol was probably a good listener. In this particular passage, he disappears into a frustratingly weird narrative of drug-fueled chores. He plays a trick by fading, chameleon-like, into the wallpaper. His friend has to make sure everything is totally sanitized and clean; he lets her wash him out of his own story. I squint, trying to detect the ego, superego, or id floating around within this Warholian matrix. Who would win in a match between A and Freud? Recent documentaries and studies of Warhol tend to sensationalize the ugliness of the man. Maybe the general public doesn’t know A suffered from tragically bad skin, baldness under his lovely wig --- or that he hardly ever enjoyed a fulfilling sex life, had to assemble himself in front of a mirror, with all sorts of pastes and products, before feeling presentable, or that he was scarred and damaged after being shot, having to wear a corset thereafter. Documentarians, filmmakers, and scholars have been trying to dramatically expose this side of Warhol; thus, I assumed it had always been hidden --- that A couldn’t stand such facts of his bodily failures, his monstrosity, incorporated under the public title of Andy Warhol. I was surprised, then, at what A, as author, was forward about when writing about his body in Philosophy. The angst of not being beautiful is typed across page after page. He wakes up and dials a number; into the phone he sighs, “I wake up every morning. I open my eyes and think: here we go again.” He wanted to look into the mirror and see nothing --- because he desired the erasure of his imperfections. He knew he didn’t really belong in the glossy magazines of the celebrities he adored, but he had to find a way to kidnap that glamour. He posits that addressing what he doesn’t like about himself is a way to erase the impact of those undesirable qualities on his life. So right away he is discussing his pimples and, as evidenced in above set-piece, many other examples of the freakish characteristics that plagued and defined him. It could have come off as a joke contemporaneously, but today we read the seriousness, and tragedy, in his comic remark: “I need about an hour to glue myself together.” Applying his artifice was time consuming. The way his wig was pasted or bound to his bald pate must have been painful; the obviousness of his weirdness and the futility to cake it over with make-up and creams must have been wholly embarrassing. Once, at a book signing, a girl grabbed off his wig and disappeared into a getaway car. Exposed, A was terrified; he later claimed that that event was equally traumatizing as being shot in the gut and almost dying. Yet, in retrospect, the details he waltzes around are telling. Although Warhol refers obliquely to his “wings,” I am unclear if that is even a fuzzy reference to his hairpieces. Anyway, in writing he claims that he has “gone gray” by dying his existing hair; he spends plenty of time turning this excuse into a demonstration of his “philosophy.” (Funny that the implicit intent of this book is to outline/codify a Warholian ideology when that concept, as such, was realized only as a mirroring of other cultural surfaces.) Was his “going gray” claim a joke or was Warhol unprepared to announce in print that the radical style of his platinum wigs was defensive in origin, meant to conceal? Before he switched to his trademark wig style, those who knew him were embarrassed for him because of how phony his more naturally colored hairpieces looked. Often, when somebody was mad at Andy, he attacked his appearance. A detail of Warhol’s biography that is contrastively ignored is his drug use --- it was easy for him to refer to taking his “vitamins” and “diet pills,” but those drugs should now be understood as amphetamines, which he was in habitual practice of swallowing (as far as I understand from my own research). The relationship of amphetamine’s grammar to the Warholian construct could benefit from further study. In Philosophy, he mentions taking pills only in passing, innocently refusing to discuss what they mean to him or his work, and he glosses the drug use that characterized his social milieu via playfully opaque euphemisms. When a “poke” (injection of drugs) is mentioned, it is unclear whether heroin or speed is the substance being abused. A also avoids bringing up his queerness, which I find incongruous considering the explicit (plus implicit) themes of queer sexuality in his art. He portrays himself as having monkish dedication to his career and, almost literally, married to his tape recorder (his “wife”); when the subject of romantic or sexual interaction arises he uses the feminine pronoun when referring to his partner. Although Warhol doesn’t seem to be able to fit within the developing model of postwar male homosexuality, he is definitely queer. He had same sex attractions and relationships, however problematic. Maybe Warhol would have made a profound contribution to queer literature had he addressed the subject in this text --- maybe he felt like he couldn’t (or did not want to). Anyway, A can be just about whatever we want; that’s why we love him so. He just can’t be himself --- not if he’s some form of simulacrum. A human subject can only be thought about in these terms abstractly. An agent like you, dear reader, can’t demonstrate yourself as a copy without an original, not in earnest (so I say, at least). That was Warhol’s project, nonetheless. He wanted to cake simulation in suffocating layers over his agency, thus creating the curtain to disappear behind forever. Advice from A: “If you can’t believe it’s happening, pretend it’s a movie.” I write about A all the time and never get any closer to solving anything; that’s the point. I don’t know, as they say. From I Am Happy: Interviewer, “What does human judgment mean to you?” Andy, “Human judgment doesn’t mean anything to me. Human judgment doesn’t exist for technology. I don’t like problems because you have to find a solution. Without judgment there can be no problems. What I try to do is avoid solving problems. Problems are too hard and too many. I don’t think finding solutions really adds up to anything --- it only creates more problems. Becoming a machine is a way of making things easy. And it gives me something to do. I like that.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)