The Corresponding Society will be starting off the new year with a monolithic reading featuring some of today’s most incredible poets, assembled by Master of Ceremonies Lonely Christopher. The event shall be staged 7 January at 7pm at Chelsea’s P.P.O.W. Gallery under the rubric of the Hostess Project. The readers shall be Rachel Zolf, Rob Fitterman, Christian Hawkey, Rachel Levitsky, and, fuck yes, Richard Loranger. While you anxiously await this happening, please accept the following blog content to hold you over. Rob Fitterman (aka Rob the plagiarist) has generously filled out a loosely interpreted version of the Proust Questionnaire, which you’ll find below. There will be more Proust Questionnaire answers, perhaps from other featured readers and definitely from some members of The Corresponding Society, to follow in the new year.

An Introduction to Robert Fitterman

Robert Fitterman is the author of 10 books of poetry including: The Sun Also Also Rises, war the musical, Metropolis XXX: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Edge Books), Metropolis 16-29 (Coach House Press), Metropolis 1-15 (Sun & Moon Press), This Window Makes Me Feel (www.ubu.com). Metropolis 1-15 was awarded the Sun & Moon “New American Poetry Award (2000)” and Metropolis 16-29 was awarded the Small Press Traffic “Book of the Year Award (2003)”. With novelist Rodrigo Rey Rosa, he co-authored the film What Sebastian Dreamt which was selected for the Sundance Film Festival (2004) and the Lincoln Center LatinBeat Festival (2004). He has been a full-time faculty member in NYU’s Liberal Studies Program since 1993. He also teaches poetry at the Milton Avery School of Graduate Studies at Bard College.

(from the NYU website)

Robert Fitterman Answers the Proust Questionnaire

Your favorite virtue.

Generosity.

Your favorite qualities in a man.

Femininity.

Your favorite qualities in a woman.

Masculinity.

Your chief characteristic.

Loyalty.

What you appreciate the most in your friends.

Loyalty.

Your main fault.

Bad with money.

Your favorite occupation.

Poet.

Your idea of happiness.

Lunch in the Italian countryside with friends and Kim and Coco.

Your idea of misery.

Not being able to do the former.

If not yourself, who would you be?

Myself.

Where would you like to live?

In NYC.

Your favorite prose authors.

My favorite authors blur this genre distinction.

Your favorite poets.

What day is it today?

Your favorite heroes in fiction.

Not much, thanks.

Your favorite heroines in fiction.

These are the pants I was telling you about.

Your favorite painters and composers.

OK, great to see you too.

Your heroes in “real life.”

Call me when you get in, OK?

What characters in history do you most dislike?

Sure, but please don't worry.

Your favorite names.

Hector & Tula.

What do you hate the most?

Badly prepared or presented or cared for or corrupted food.

Monday, December 28, 2009

Monday, December 7, 2009

Poetry Project

Lonely Christopher and Rebecca Nagle will be reading this Friday at the Poetry Project. Here's more information:

The Poetry Project

131 E. 10th Street, Manhattan

LC & RN 11 Dec @ 10pm!

LONELY CHRISTOPHER writes across forms; he is a poet, playwright, director, editor, and unpublished novelist. His poetry has been collected in the chapbooks Satan (Small Anchor) and Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land? (No Know) and the first two installments of his Gay Plays, a trilogy of dramatic explorations into the queer situation, have been released together by Small Anchor. Withal, the Gay Plays have been staged internationally and published in China in a Mandarin translation. He is a founding member of the Corresponding Society, the manager of its blog, and an editor of its biannual literary journal Correspondence; he is the curator of the press’ second series of poetry chapbooks What Where (forthcoming in winter). He lives in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn.

REBECCA NAGLE is a performance, new media and community artist. She grew up in Kansas. After attending Interlochen Arts Academy, she studied at Maryland Institute College of Art. She is an internationally exhibited and collected artist with works in the New Museum, NY and Ssamzie Art Warehouse, South Korea. Nagle has shown at Current Gallery, Art in General, Site Santa Fe, Artscape, and Conflux Festival. She was hailed by Baltimore City’s Paper’s senior arts editor Bret McCabe as “Baltimore’s very own life-is-art-is-life performance maven…mingling the internet and performance into a fresh and vital new thing”. Rebecca’s performative, interative and community art projects challenge people around issues of intimacy, the body, power, boundaries and efficacy. She is currently trying to make the world a more open, equitable and creative place through community organizing and radical performance art.

THE FRIDAY NIGHT SERIES was born in 1991 & raised by poet/author Gillian McCain (Tilt, Religion, & co-author of Please Kill Me with Leggs McNeil); it been a bi-monthly forum for multi-media events & other “untraditional” literary going-ons. The Friday Night Series varies its programming with a combination of readings, presentations, performances, screenings & installations – theatrical, visual, textual, musical or otherwise. All events start at 10PM & end at/around MIDNIGHT, unless otherwise noted. The Fall 2009 - Spring 2010 season will be co-curated by Edward Hopely and Nicole Wallace.

The Poetry Project

131 E. 10th Street, Manhattan

LC & RN 11 Dec @ 10pm!

LONELY CHRISTOPHER writes across forms; he is a poet, playwright, director, editor, and unpublished novelist. His poetry has been collected in the chapbooks Satan (Small Anchor) and Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land? (No Know) and the first two installments of his Gay Plays, a trilogy of dramatic explorations into the queer situation, have been released together by Small Anchor. Withal, the Gay Plays have been staged internationally and published in China in a Mandarin translation. He is a founding member of the Corresponding Society, the manager of its blog, and an editor of its biannual literary journal Correspondence; he is the curator of the press’ second series of poetry chapbooks What Where (forthcoming in winter). He lives in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn.

REBECCA NAGLE is a performance, new media and community artist. She grew up in Kansas. After attending Interlochen Arts Academy, she studied at Maryland Institute College of Art. She is an internationally exhibited and collected artist with works in the New Museum, NY and Ssamzie Art Warehouse, South Korea. Nagle has shown at Current Gallery, Art in General, Site Santa Fe, Artscape, and Conflux Festival. She was hailed by Baltimore City’s Paper’s senior arts editor Bret McCabe as “Baltimore’s very own life-is-art-is-life performance maven…mingling the internet and performance into a fresh and vital new thing”. Rebecca’s performative, interative and community art projects challenge people around issues of intimacy, the body, power, boundaries and efficacy. She is currently trying to make the world a more open, equitable and creative place through community organizing and radical performance art.

THE FRIDAY NIGHT SERIES was born in 1991 & raised by poet/author Gillian McCain (Tilt, Religion, & co-author of Please Kill Me with Leggs McNeil); it been a bi-monthly forum for multi-media events & other “untraditional” literary going-ons. The Friday Night Series varies its programming with a combination of readings, presentations, performances, screenings & installations – theatrical, visual, textual, musical or otherwise. All events start at 10PM & end at/around MIDNIGHT, unless otherwise noted. The Fall 2009 - Spring 2010 season will be co-curated by Edward Hopely and Nicole Wallace.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

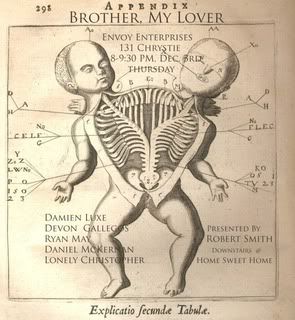

Brother Lover

The new installment of Robert Smith's queer reading series featuring Damien Luxe, Devon Gallegos, Ryan May, Daniel McKernan, and Lonely Christopher! This Thursday at Envoy Enterprises! Read an interview with Robert Smith here.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Revenge Hamlet!

Hamlet’s Dad from Hell

a terrific misreading

by Lonely Christopher

The villain of Hamlet is the ghost: a spectral dad beckoning his entire family to murder. Hamlet basically: a supernatural revenge thriller where some fancy-costumed royalty frown and yell in a haunted castle before they all kill each other. Every bad thing happens in the play because of the ghost, who is already menacing some poor sentinels at the very outset. Admittedly, the ghost (who undeniably exists, that is he’s not hallucinated, according to the play’s dramatic logic) happened to become so phantomy because he was murdered. Withal, the regicidal villain (his bro, ouch) forthwith assumed his victim’s crown and wife. Unfortunately for undead Old Hamlet, he was a prayer shy of heaven thus imprisoned as a disappointed wraith. Still, to apply a worn axiom, two wrongs don’t make a right. Demanding his melancholy son to perform unspecified revenge (hint: probably stabbing) has no nutritional value outside restoring nominal moral order to the court. (Restoring morality when nobody realizes the crime even happened would mean, for most involved, having to create the problem in order to solve it.) The ghost doesn’t think about the consequences and doesn’t want Hamlet to tarry either. His spooky instructions aren’t very helpful (not to mention delivered with Satanic theatrics that end up traumatizing his son) --- and even if Hamlet had immediately followed through in deposing Claudius (in such a way that was recognized as just by all), the political result would probably include being conquered by Norway. Claudius had to poison his own brother to achieve the crown, but he was diplomatically competent enough to do so in such a way that nobody suspected his crime; he also seemed to be expertly managing/resolving the threat of foreign invasion --- Hamlet doesn’t have very mature problem solving skills and, considering his mental illness withal (that is, melancholia not his fake antic disposition), his future as a leader is suspect. We know Old Hamlet was brave in combat, but if he was as reckless alive as dead, maybe Denmark ended up better off with Claudius. After “stealing” the vacant throne from Hamlet by being elected, Claudius is a little worried about further hurting his sensitive nephew’s feelings (hence telling him to drop out of school the better to be monitored at home), but otherwise he treats Hamlet like a stepfather who just wants to be liked. Meanwhile, Hamlet’s real dad is back from hell (okay, purgatory), lurking around battlements, and haunting his son screeching terrible, unfounded accusations and demands for revenge. Horatio warns that the ghost might be a disguised devil --- the kind that has fun driving melancholiacs to madness before pushing them off cliffs (it was a different time). Even if the ghost is honest that doesn’t stop him from causing a far bloodier end than a crazy leap off a cliff. Some claim that this is a play about skepticism. Olivier famously introduced his film version as a story about a man who couldn’t make up his mind. The thematic scope is larger, though, because Hamlet agonizes over more than critical indecision. The problem is so much more enormous than helping a ghost --- the problem is the nature of the ghost attack itself. When dad visits him from his nether-universe of negation, Hamlet’s brain comes unstuck from the dramatic context of this royal thriller and everything problematizes doing anything (he’s dissociated). Hamlet dearly hopes, once shuffled off this mortal coil, the rest is silence --- after his transfiguration into a failure hero, all the mental torture, and having caused the death of almost everybody around him (including two women he loved), there better be a universe of nothing but silence waiting because the joke just keeps getting worse if he ends up burning with dad in purgatory. We’ve Old Hamlet’s posthumous bad parenting to thank for the mess that makes up the play (without the ghost the action would be limited to Hamlet moping around Elsinore whining about how slutty his mom is); the revenge hungry spook is the foundational conceit of the narrative progression. Hamlet goes kind of crazy (offstage and hatless) over the problem of the ghost’s nature and purpose. He wonders if the figure of his father is a spirit of health or goblin damned. The former doesn’t really fit, considering the suicide mission the ghost pushes Hamlet into; whether demon or dead king the apparition has no concern for Hamlet’s wellbeing --- he wants to be remembered, damn it, and avenged! --- and only pokes his floaty head into the action once more to threaten to spank Hamlet for wasting time in killing more of the court (he’s not too happy about the boy slapping his mother around, either, more evidence of his selective morality). If he just slept on it another night maybe the ghost would have given Hamlet different advice: “I’m upset your uncle killed me for my wife and crown --- not to mention before my sins were forgiven, so I’m a damn ghost purging my misdeeds in flame most of the day --- but since we didn’t get to talk before brain-melting distilment was poured in my ear porches, I just want you to know I love ya. I realize you expected to be my heir when I died, but don’t let it get you down; first of all, the king is elected by popular vote, so you would have had to campaign (no fun), and also you’re still a teenager and way more interested in demonology and theater than international politics --- maybe one day, kid. And hey: I know she let us down, but take care of your mom, that slut, and be nice to your girlfriend because she’s fragile --- oh, and stay in school. Also, no big deal, but please at some point kill your uncle. Eye for an eye, right? But only when you feel ready.” Oh well! Old Hamlet wasn’t the only problem father of the play. Fortinbras’ dad was irresponsible enough to get killed (by Old Hamlet no less) in a macho land gamble and Polonius messed his daughter the fuck up and paid a spy to follow his son while spreading rumors he likes prostitutes. These hapless children, following Hamlet’s example, idolized their fathers even when doing so played directly into harm that the fathers were usually responsible for. Polonius is a real jerk to Ophelia (at least way overprotective), but she continues to love him so much that when he’s killed she goes crazy, falls out of a tree, and drowns. Fittingly, the bloodbath finale begins with a showdown between two kids with dead dads, both after bloody revenge. At that point Hamlet’s heart isn’t even in it anymore; he just wants to get it over with already. And: everyone dies. Except Horatio, he survives everybody and, coincidentally, never mentions his father the whole play.

a terrific misreading

by Lonely Christopher

The villain of Hamlet is the ghost: a spectral dad beckoning his entire family to murder. Hamlet basically: a supernatural revenge thriller where some fancy-costumed royalty frown and yell in a haunted castle before they all kill each other. Every bad thing happens in the play because of the ghost, who is already menacing some poor sentinels at the very outset. Admittedly, the ghost (who undeniably exists, that is he’s not hallucinated, according to the play’s dramatic logic) happened to become so phantomy because he was murdered. Withal, the regicidal villain (his bro, ouch) forthwith assumed his victim’s crown and wife. Unfortunately for undead Old Hamlet, he was a prayer shy of heaven thus imprisoned as a disappointed wraith. Still, to apply a worn axiom, two wrongs don’t make a right. Demanding his melancholy son to perform unspecified revenge (hint: probably stabbing) has no nutritional value outside restoring nominal moral order to the court. (Restoring morality when nobody realizes the crime even happened would mean, for most involved, having to create the problem in order to solve it.) The ghost doesn’t think about the consequences and doesn’t want Hamlet to tarry either. His spooky instructions aren’t very helpful (not to mention delivered with Satanic theatrics that end up traumatizing his son) --- and even if Hamlet had immediately followed through in deposing Claudius (in such a way that was recognized as just by all), the political result would probably include being conquered by Norway. Claudius had to poison his own brother to achieve the crown, but he was diplomatically competent enough to do so in such a way that nobody suspected his crime; he also seemed to be expertly managing/resolving the threat of foreign invasion --- Hamlet doesn’t have very mature problem solving skills and, considering his mental illness withal (that is, melancholia not his fake antic disposition), his future as a leader is suspect. We know Old Hamlet was brave in combat, but if he was as reckless alive as dead, maybe Denmark ended up better off with Claudius. After “stealing” the vacant throne from Hamlet by being elected, Claudius is a little worried about further hurting his sensitive nephew’s feelings (hence telling him to drop out of school the better to be monitored at home), but otherwise he treats Hamlet like a stepfather who just wants to be liked. Meanwhile, Hamlet’s real dad is back from hell (okay, purgatory), lurking around battlements, and haunting his son screeching terrible, unfounded accusations and demands for revenge. Horatio warns that the ghost might be a disguised devil --- the kind that has fun driving melancholiacs to madness before pushing them off cliffs (it was a different time). Even if the ghost is honest that doesn’t stop him from causing a far bloodier end than a crazy leap off a cliff. Some claim that this is a play about skepticism. Olivier famously introduced his film version as a story about a man who couldn’t make up his mind. The thematic scope is larger, though, because Hamlet agonizes over more than critical indecision. The problem is so much more enormous than helping a ghost --- the problem is the nature of the ghost attack itself. When dad visits him from his nether-universe of negation, Hamlet’s brain comes unstuck from the dramatic context of this royal thriller and everything problematizes doing anything (he’s dissociated). Hamlet dearly hopes, once shuffled off this mortal coil, the rest is silence --- after his transfiguration into a failure hero, all the mental torture, and having caused the death of almost everybody around him (including two women he loved), there better be a universe of nothing but silence waiting because the joke just keeps getting worse if he ends up burning with dad in purgatory. We’ve Old Hamlet’s posthumous bad parenting to thank for the mess that makes up the play (without the ghost the action would be limited to Hamlet moping around Elsinore whining about how slutty his mom is); the revenge hungry spook is the foundational conceit of the narrative progression. Hamlet goes kind of crazy (offstage and hatless) over the problem of the ghost’s nature and purpose. He wonders if the figure of his father is a spirit of health or goblin damned. The former doesn’t really fit, considering the suicide mission the ghost pushes Hamlet into; whether demon or dead king the apparition has no concern for Hamlet’s wellbeing --- he wants to be remembered, damn it, and avenged! --- and only pokes his floaty head into the action once more to threaten to spank Hamlet for wasting time in killing more of the court (he’s not too happy about the boy slapping his mother around, either, more evidence of his selective morality). If he just slept on it another night maybe the ghost would have given Hamlet different advice: “I’m upset your uncle killed me for my wife and crown --- not to mention before my sins were forgiven, so I’m a damn ghost purging my misdeeds in flame most of the day --- but since we didn’t get to talk before brain-melting distilment was poured in my ear porches, I just want you to know I love ya. I realize you expected to be my heir when I died, but don’t let it get you down; first of all, the king is elected by popular vote, so you would have had to campaign (no fun), and also you’re still a teenager and way more interested in demonology and theater than international politics --- maybe one day, kid. And hey: I know she let us down, but take care of your mom, that slut, and be nice to your girlfriend because she’s fragile --- oh, and stay in school. Also, no big deal, but please at some point kill your uncle. Eye for an eye, right? But only when you feel ready.” Oh well! Old Hamlet wasn’t the only problem father of the play. Fortinbras’ dad was irresponsible enough to get killed (by Old Hamlet no less) in a macho land gamble and Polonius messed his daughter the fuck up and paid a spy to follow his son while spreading rumors he likes prostitutes. These hapless children, following Hamlet’s example, idolized their fathers even when doing so played directly into harm that the fathers were usually responsible for. Polonius is a real jerk to Ophelia (at least way overprotective), but she continues to love him so much that when he’s killed she goes crazy, falls out of a tree, and drowns. Fittingly, the bloodbath finale begins with a showdown between two kids with dead dads, both after bloody revenge. At that point Hamlet’s heart isn’t even in it anymore; he just wants to get it over with already. And: everyone dies. Except Horatio, he survives everybody and, coincidentally, never mentions his father the whole play.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Video Sample

Correspondence No. 3 shall arrive around the end of the year according to best estimates. Wise literates would do well to prepare for the delirious pleasure this document will bring. Really, it’s dangerous. Because we’re responsible please find below a sort of preview, which the reader might use as a patient does a flu shot to protect her body against a virus. In this example, the virus is words and also it’s a good virus. It’s just a little much and we don’t want readers to get hurt. Well, yes, emotionally we want to damage readers. We just don’t want to permanently injure them with the majuscule poetic force contained within this forthcoming volume/weapon. So here is a taste, which is a video record of Ray Ray Mitrano performing something to be found in the pages of No. 3. It is called “Italy When Three.”

Italy When Three from RAY RAY MITRANO on Vimeo.

Monday, November 9, 2009

Wide Eyes

Negative Nice

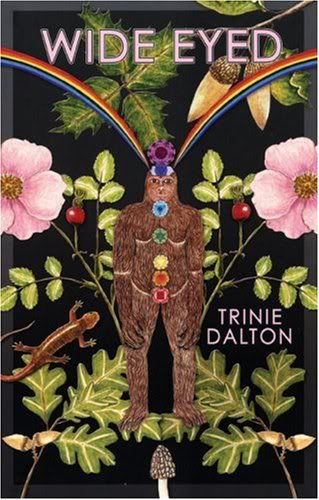

Trinie Dalton’s short fiction is darling and traumatic

by Lonely Christopher

The cover art of Trinie Dalton’s book Wide Eyed, put out aught-five by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery series from Akashic, features author-drawn illustrations of flowers, rainbows, unicorns, and a bigfoot type creature. I remembered the cover from seeing it at a bookstore a while ago; when I asked a friend about it he told me the cover was a good indication of the content and now I agree. What’s funny is that the collection is so magnificent. It has so many conceptual strikes against it, worst of all being creative writing, viz. fiction, published this decade. The persistence of kitsch (unicorns, for a start), the clever randomness (whimsical unpredictability!), and the ironic cultural references (the Flaming Lips, 80’s slasher flicks, Disney) are techniques shared with hipster fiction of the most abhorrent variety (unimportantly plaguing the aughts, hipster fiction is something we’re going to have to go back in a time machine to prevent). Dalton proves the same things that we’ve seen so abused by a whole youth culture can be used without guilt with delightfully winning results. She’s too mature to ruin the form like younger kids are and too clever to ruin the form like writers her age are. This is a compliment and a joy.

Anyway, if the stories were all sugar, narrated as they are by a very similar voice and personality that’s almost a sort of Amelie from a negative dimension, this writing would be impossible to stomach. What makes it work is how a Cooper-like disgust or anxiety spoons in a frilly bed with the ingenuous cuteness. This is a pretty fucked-up book --- plus it’s adorable. The Ben Marcus blurb on the back, which only praises aspects of innocence, love, and wonder, makes me suspect either Ben Marcus didn’t read Wide Eyed or else he’s a pretty disturbed person. These stories are ugly/pretty: a sinister violence becomes the undertow in a sparkling sun-kissed lazy river. The quality of this sentence is representative: “When I was in elementary school and first learned about the realities of rape, I remember riding home on the bus from a field trip to Disneyland and wishing I had been dragged into Adventureland, then raped behind Thunder Mountain.” No other contemporary work I can think of so vividly captures a world where everything being so not okay hurts but can’t murder being a happy person.

Nobody can do anything right and even when that fact is benign it’s still a lurking threat. The obsessions with unicorns, elves, woodland and sea creatures, botany, childhood, and candy only prove the darkness of these stories, which are about the awkward pleasures of aloneness, the façade of normalcy being punctured by humanity’s underlying ugliness, and the pathological failures of people to negotiate each other cleanly. Try writing a story in pen pal letters between a lonely woman-child and an elf from the North Pole without making anybody with halfway-developed critical faculties find you and take some sort of revenge. Well, that’s not the strongest story here, but she pulled off okay the elf thing and I have no clue how (what sounds feasible about “pulling off the elf thing”?). Dalton uses the shorter short fiction form to her advantage. There was no story (most are about five pages in the largest font you can sort of get away with) I wanted to be longer. She knows how long something can go on for; depth accumulates, but each story is a few weirdly shallow gasps. The episode I found most arresting was part of an essayish triptych anecdotally describing how things, blood namely, can come to drool across floor tile. This particular section of the barely six-page piece is less than two pages; it depicts in careful/squirmy portraiture the event of a boy taking a shower in a scummy apartment and a “mutant salamander” emerging from the drain. The result is not hygienic or pleasant, but demonstrating an economy of discomfort and Lilliputian trauma.

The story of an attempt at throwing a house party begins ruined by a guest, missing a shoe, breathlessly approaching the host: “‘Your fucking friend just attacked me,’ she says. She was in my basement music room so no one heard her yelling through the egg-crate covered walls. I’m hosting a Hawaiian-themed party.” The creep who stole the girl’s shoe after harassing her is a total failure who can’t quite fit well enough into the way things go and who suffers from crippling social problems. The narrator, who herself has positive intentions (a nice luau, like what? the details of the music room being pretty heartbreaking, too), tries to understand the creep: “He didn’t seem dangerous, just fetishistic.” Another story begins similarly with the narrator and her boyfriend Matt having a “luxury” pork meal to celebrate his latest painting. The painting is “as long as a Honda, and as tall as our ceiling. Red-barked trees, squirrels, and naked women cover the canvas.” The constant miracle of this book is that it never slouches into lazy Napoleon Dynamite twee/preciousness; despite how close it comes it then swoops back into the realm of literary skill as assuredly as a stunt pilot pulling out of a nosedive right before hitting the water. The turn in this flash-length storylet is when Matt can’t stop himself from doing the “wrong” thing (he eats all the copious pork leftovers cold for breakfast: “I just ate a huge pile of lard, basically”), getting miserably ill as consequence, and the narrator can’t help but desiring him more for his disabled judgment. Elsewhere: the narrator imagining she is Snow White --- with glass coffin, singing chipmunks, and all --- during a sexual encounter in her backyard garden. The scene is tenderly pathetic and, ultimately, emotionally affirmative (hell, wide eyed). “Everything went white as I came, as if the moon suddenly got brighter.” Most of the characters in these stories act like high functioning autistics. When the simplest aspects of getting by in life are rendered as impossibly fraught, the result is highly unnerving as safety divorces from routine. The balance between childish awe and psycho nervousness is the best hit of Wide Eyed. There is no reason this book works more than that Trinie Dalton has a major handle on her craft and knows how to channel her bizarre fixations (is that me projecting?) into the kind of art that you appreciate as it makes you feel uneasy about the world.

Trinie Dalton’s short fiction is darling and traumatic

by Lonely Christopher

The cover art of Trinie Dalton’s book Wide Eyed, put out aught-five by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery series from Akashic, features author-drawn illustrations of flowers, rainbows, unicorns, and a bigfoot type creature. I remembered the cover from seeing it at a bookstore a while ago; when I asked a friend about it he told me the cover was a good indication of the content and now I agree. What’s funny is that the collection is so magnificent. It has so many conceptual strikes against it, worst of all being creative writing, viz. fiction, published this decade. The persistence of kitsch (unicorns, for a start), the clever randomness (whimsical unpredictability!), and the ironic cultural references (the Flaming Lips, 80’s slasher flicks, Disney) are techniques shared with hipster fiction of the most abhorrent variety (unimportantly plaguing the aughts, hipster fiction is something we’re going to have to go back in a time machine to prevent). Dalton proves the same things that we’ve seen so abused by a whole youth culture can be used without guilt with delightfully winning results. She’s too mature to ruin the form like younger kids are and too clever to ruin the form like writers her age are. This is a compliment and a joy.

Anyway, if the stories were all sugar, narrated as they are by a very similar voice and personality that’s almost a sort of Amelie from a negative dimension, this writing would be impossible to stomach. What makes it work is how a Cooper-like disgust or anxiety spoons in a frilly bed with the ingenuous cuteness. This is a pretty fucked-up book --- plus it’s adorable. The Ben Marcus blurb on the back, which only praises aspects of innocence, love, and wonder, makes me suspect either Ben Marcus didn’t read Wide Eyed or else he’s a pretty disturbed person. These stories are ugly/pretty: a sinister violence becomes the undertow in a sparkling sun-kissed lazy river. The quality of this sentence is representative: “When I was in elementary school and first learned about the realities of rape, I remember riding home on the bus from a field trip to Disneyland and wishing I had been dragged into Adventureland, then raped behind Thunder Mountain.” No other contemporary work I can think of so vividly captures a world where everything being so not okay hurts but can’t murder being a happy person.

Nobody can do anything right and even when that fact is benign it’s still a lurking threat. The obsessions with unicorns, elves, woodland and sea creatures, botany, childhood, and candy only prove the darkness of these stories, which are about the awkward pleasures of aloneness, the façade of normalcy being punctured by humanity’s underlying ugliness, and the pathological failures of people to negotiate each other cleanly. Try writing a story in pen pal letters between a lonely woman-child and an elf from the North Pole without making anybody with halfway-developed critical faculties find you and take some sort of revenge. Well, that’s not the strongest story here, but she pulled off okay the elf thing and I have no clue how (what sounds feasible about “pulling off the elf thing”?). Dalton uses the shorter short fiction form to her advantage. There was no story (most are about five pages in the largest font you can sort of get away with) I wanted to be longer. She knows how long something can go on for; depth accumulates, but each story is a few weirdly shallow gasps. The episode I found most arresting was part of an essayish triptych anecdotally describing how things, blood namely, can come to drool across floor tile. This particular section of the barely six-page piece is less than two pages; it depicts in careful/squirmy portraiture the event of a boy taking a shower in a scummy apartment and a “mutant salamander” emerging from the drain. The result is not hygienic or pleasant, but demonstrating an economy of discomfort and Lilliputian trauma.

The story of an attempt at throwing a house party begins ruined by a guest, missing a shoe, breathlessly approaching the host: “‘Your fucking friend just attacked me,’ she says. She was in my basement music room so no one heard her yelling through the egg-crate covered walls. I’m hosting a Hawaiian-themed party.” The creep who stole the girl’s shoe after harassing her is a total failure who can’t quite fit well enough into the way things go and who suffers from crippling social problems. The narrator, who herself has positive intentions (a nice luau, like what? the details of the music room being pretty heartbreaking, too), tries to understand the creep: “He didn’t seem dangerous, just fetishistic.” Another story begins similarly with the narrator and her boyfriend Matt having a “luxury” pork meal to celebrate his latest painting. The painting is “as long as a Honda, and as tall as our ceiling. Red-barked trees, squirrels, and naked women cover the canvas.” The constant miracle of this book is that it never slouches into lazy Napoleon Dynamite twee/preciousness; despite how close it comes it then swoops back into the realm of literary skill as assuredly as a stunt pilot pulling out of a nosedive right before hitting the water. The turn in this flash-length storylet is when Matt can’t stop himself from doing the “wrong” thing (he eats all the copious pork leftovers cold for breakfast: “I just ate a huge pile of lard, basically”), getting miserably ill as consequence, and the narrator can’t help but desiring him more for his disabled judgment. Elsewhere: the narrator imagining she is Snow White --- with glass coffin, singing chipmunks, and all --- during a sexual encounter in her backyard garden. The scene is tenderly pathetic and, ultimately, emotionally affirmative (hell, wide eyed). “Everything went white as I came, as if the moon suddenly got brighter.” Most of the characters in these stories act like high functioning autistics. When the simplest aspects of getting by in life are rendered as impossibly fraught, the result is highly unnerving as safety divorces from routine. The balance between childish awe and psycho nervousness is the best hit of Wide Eyed. There is no reason this book works more than that Trinie Dalton has a major handle on her craft and knows how to channel her bizarre fixations (is that me projecting?) into the kind of art that you appreciate as it makes you feel uneasy about the world.

Monday, November 2, 2009

Word's Way

From our friends at Republic Brooklyn:

REPUBLIC Worldwide Presents

WAY OF THE WORD

Wednesday November 11, 2009

7 pm-11 pm

Bar On A

170 Avenue A (between 10th St & 11th St)

It is in the spirit of language arts that REPUBLIC presents the first installment of its recurring “Way of the Word” program at Bar On A.

WAY OF THE WORD is a unique evening of art, poetry, performance and music by emerging artists in the New York poetry world.

Visual Poets include: Edward Hopely, Brian VanRemmen and more

Slam poets: Khephran Riddick and Aldrin Valdez

Traditional poets: Davey Vacek, Katie Przybylski, Marissa Forbes, Peter Ford, and three founding members of a Brooklyn based poetry group called The Corresponding Society --- Lonely Christopher, Robert Snyderman, and Jason Tallon.

Doors open at 7pm with a visual and interactive gallery hour for the artists, poets, and guests before the poetry readings begin at 8pm.

Drink specials from 7 to 9pm. Bar On A

“Way of the Word” represents the idea that words take on wills of their own, depending on how they’re put on the page and how a reader perceives them. A short event anthology, featuring poets from the show and around the nation will be available for purchase online and at the door for $15.

Portions of the proceeds will be donated to Reading Excellence and Discovery (READ), a foundation that promotes literacy by pairing qualified high school tutors with elementary students who demonstrate below grade level reading skills.

For more information about “Way of the Word,” READ or REPUBLIC please contact jason@republicbrooklyn.com or call 443. 528. 6761 or 917. 273. 2712

REPUBLIC Worldwide Presents

WAY OF THE WORD

Wednesday November 11, 2009

7 pm-11 pm

Bar On A

170 Avenue A (between 10th St & 11th St)

It is in the spirit of language arts that REPUBLIC presents the first installment of its recurring “Way of the Word” program at Bar On A.

WAY OF THE WORD is a unique evening of art, poetry, performance and music by emerging artists in the New York poetry world.

Visual Poets include: Edward Hopely, Brian VanRemmen and more

Slam poets: Khephran Riddick and Aldrin Valdez

Traditional poets: Davey Vacek, Katie Przybylski, Marissa Forbes, Peter Ford, and three founding members of a Brooklyn based poetry group called The Corresponding Society --- Lonely Christopher, Robert Snyderman, and Jason Tallon.

Doors open at 7pm with a visual and interactive gallery hour for the artists, poets, and guests before the poetry readings begin at 8pm.

Drink specials from 7 to 9pm. Bar On A

“Way of the Word” represents the idea that words take on wills of their own, depending on how they’re put on the page and how a reader perceives them. A short event anthology, featuring poets from the show and around the nation will be available for purchase online and at the door for $15.

Portions of the proceeds will be donated to Reading Excellence and Discovery (READ), a foundation that promotes literacy by pairing qualified high school tutors with elementary students who demonstrate below grade level reading skills.

For more information about “Way of the Word,” READ or REPUBLIC please contact jason@republicbrooklyn.com or call 443. 528. 6761 or 917. 273. 2712

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Get Know!

Know: “No Know” is here --- The Corresponding Society’s premiere line of poetry chapbooks --- representing the following exciting verse collections contained in finely-wrought limited editions: “Elegies for A.R. Ammons” by David Swensen; “This Pose Can Be Held for Only So Long” by Caroline Gormley; “Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land?” by Lonely Christopher. Read more and see withal:

When, Why, How, Who, Know

The Corresponding Society was founded to publish our journal Correspondence, third issue arriving almost-presently, and for some time the moral, mental, and monetary expense of that undertaking alone distracted us from thoughts of multiple directions. Also, at an early meeting, somebody chanced to scream, “There is no way we are doing chapbooks!” and it took a while to schedule a review of that declaration. Around the time we went so far as to release the online chapbook The Gates Salon (Thursday) by (issue three cover artist and contributor) Ray-Ray Mitrano, readable here, the project of a series of single-author poetry chapbooks was being proposed by (one of the founding editors) Robert Snyderman. The chapbook, a sexily intimate object as far as vehicles for poetry go, presents quite a different form than the anthologizing hulk of a literary journal. The latter’s crowded gloriously with a noisy gymfull of different writers, voices rubbing around the pages in discursive concert (the order of the work has to be arranged carefully, like an arty mix-tape); the former’s singular and allows breathing room for a particular voice to stretch --- a single-source poetry architected to have space with itself between the folded cover pages. Also, whereas Correspondence releases in a perfect-bound, professionally printed version, the craft of the chapbook is intensely personal and susceptible to cultish attention. A finely-made chapbook is a fetish object in some literary circles. There was a tremendous argument for embarking on the adventure of a chapbook line and Mr. Snyderman initiated the effort by curating a triad of titles from poets he admired and wanted new published projects from. Almost immediately, Robert fled the country and became an illegal alien roaming Quebec and environs, working as a migrant farmhand and traveling/ditch-sleeping with a French-Canadian painter he met on a beach. Fortunately, Sonia Farmer and Caroline Gormley had accepted duties as the artistic directors of what Robert had named the “No Know” series; thus work was able to continue through the summer. Actually, the two art directors also fled the region presently --- on a protracted homeland visitation to the Bahamas and a relocation to Austin, TX respectively --- but not before covers were produced by letter press process, which makes for fucking handsome chapbook covers. The books came individually from terrifically disparate poetic sensibilities, yet from writers who had been working very closely as peers for many years. When presented all three at readings, the texts play strangely off each other, inciting formal resonances through elegiac examination, across the pages of modernist literature sweeping some words onto new surfaces, and around a legion of social voices stolen into new rhetorical contexts. The pitches of these poems range from conceptually personal, personally textual, and textually sociopolitical. The innocent editors, who volunteered the man-hours required to stitch and otherwise prepare these limited editions, were nearly destroyed by the fairly simple task of sewing paper, but everyone involved argues the sacrifice --- for what “No Know” offers, if the dear reader cares to discover, are important introductions to the writerly projects of three distinct young directions.

Know More No

The three titles are available at select NYC book merchants and, conveniently, here for purchase through our online store. For a limited time, orders placed online will enjoy free shipping.

Each title is published in a limited edition of 50 copies, is pamphlet stitched, and features a letterpress printed cover. Learn about them:

Elegies for A.R. Ammons by David Swensen

These are poems for the late Ammons written as the true elegy must be. They do not lament the lost poet, but attempt to wade into and harvest from his work. They integrate the landscapes of Swensen’s North Carolinian childhood with scenes from his more recent life in Scotland and New York, commemorating Ammons by constantly pressing at his colloquial --- at times ribald --- style, keeping alive Ammons’ work as it is pressed into new and vital forms.

This Pose Can Be Held for Only So Long by Caroline Gormley

A personal geography and map of the Texan Gulf Coast viewed through the eyes of youth. The poem strives to recreate that lost landscape by whatever means available --- at once using traditional poetic forms as well as combining the dissolving documents of childhood, with selected erasures of major 20th century American novels.

Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land? by Lonely Christopher

With the utmost precision and economy, Lonely Christopher addresses in Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land? the contemporary queer political sphere through questions of linguistics, conducting his subjects into a terse, wry, and ultimately operatic chorus of commentary.

"By eloquently rearranging the detritus of our national debate about gay rights, Lonely Christopher’s biting, anti-poetic poetry shows us the heights of pathos and the depths of foolishness around the issue, while delightfully mixing sexuality with textuality."

--- James Hannaham (author of God Says No)

Also know: the entire series is purchasable for fifteen dollars together. Get know.

When, Why, How, Who, Know

The Corresponding Society was founded to publish our journal Correspondence, third issue arriving almost-presently, and for some time the moral, mental, and monetary expense of that undertaking alone distracted us from thoughts of multiple directions. Also, at an early meeting, somebody chanced to scream, “There is no way we are doing chapbooks!” and it took a while to schedule a review of that declaration. Around the time we went so far as to release the online chapbook The Gates Salon (Thursday) by (issue three cover artist and contributor) Ray-Ray Mitrano, readable here, the project of a series of single-author poetry chapbooks was being proposed by (one of the founding editors) Robert Snyderman. The chapbook, a sexily intimate object as far as vehicles for poetry go, presents quite a different form than the anthologizing hulk of a literary journal. The latter’s crowded gloriously with a noisy gymfull of different writers, voices rubbing around the pages in discursive concert (the order of the work has to be arranged carefully, like an arty mix-tape); the former’s singular and allows breathing room for a particular voice to stretch --- a single-source poetry architected to have space with itself between the folded cover pages. Also, whereas Correspondence releases in a perfect-bound, professionally printed version, the craft of the chapbook is intensely personal and susceptible to cultish attention. A finely-made chapbook is a fetish object in some literary circles. There was a tremendous argument for embarking on the adventure of a chapbook line and Mr. Snyderman initiated the effort by curating a triad of titles from poets he admired and wanted new published projects from. Almost immediately, Robert fled the country and became an illegal alien roaming Quebec and environs, working as a migrant farmhand and traveling/ditch-sleeping with a French-Canadian painter he met on a beach. Fortunately, Sonia Farmer and Caroline Gormley had accepted duties as the artistic directors of what Robert had named the “No Know” series; thus work was able to continue through the summer. Actually, the two art directors also fled the region presently --- on a protracted homeland visitation to the Bahamas and a relocation to Austin, TX respectively --- but not before covers were produced by letter press process, which makes for fucking handsome chapbook covers. The books came individually from terrifically disparate poetic sensibilities, yet from writers who had been working very closely as peers for many years. When presented all three at readings, the texts play strangely off each other, inciting formal resonances through elegiac examination, across the pages of modernist literature sweeping some words onto new surfaces, and around a legion of social voices stolen into new rhetorical contexts. The pitches of these poems range from conceptually personal, personally textual, and textually sociopolitical. The innocent editors, who volunteered the man-hours required to stitch and otherwise prepare these limited editions, were nearly destroyed by the fairly simple task of sewing paper, but everyone involved argues the sacrifice --- for what “No Know” offers, if the dear reader cares to discover, are important introductions to the writerly projects of three distinct young directions.

Know More No

The three titles are available at select NYC book merchants and, conveniently, here for purchase through our online store. For a limited time, orders placed online will enjoy free shipping.

Each title is published in a limited edition of 50 copies, is pamphlet stitched, and features a letterpress printed cover. Learn about them:

Elegies for A.R. Ammons by David Swensen

These are poems for the late Ammons written as the true elegy must be. They do not lament the lost poet, but attempt to wade into and harvest from his work. They integrate the landscapes of Swensen’s North Carolinian childhood with scenes from his more recent life in Scotland and New York, commemorating Ammons by constantly pressing at his colloquial --- at times ribald --- style, keeping alive Ammons’ work as it is pressed into new and vital forms.

This Pose Can Be Held for Only So Long by Caroline Gormley

A personal geography and map of the Texan Gulf Coast viewed through the eyes of youth. The poem strives to recreate that lost landscape by whatever means available --- at once using traditional poetic forms as well as combining the dissolving documents of childhood, with selected erasures of major 20th century American novels.

Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land? by Lonely Christopher

With the utmost precision and economy, Lonely Christopher addresses in Wow, Where Do You Come from, Upside-Down Land? the contemporary queer political sphere through questions of linguistics, conducting his subjects into a terse, wry, and ultimately operatic chorus of commentary.

"By eloquently rearranging the detritus of our national debate about gay rights, Lonely Christopher’s biting, anti-poetic poetry shows us the heights of pathos and the depths of foolishness around the issue, while delightfully mixing sexuality with textuality."

--- James Hannaham (author of God Says No)

Also know: the entire series is purchasable for fifteen dollars together. Get know.

Friday, October 9, 2009

The Epistemology of Emo

Mae Saslaw was last month's guest editor. She has just gotten to writing her second post.

Her pieces have appeared in Correspondence 1 & 2, and more of her work is available at maesaslaw.wordpress.com.

Some months ago, The Correspondence Society and friends wrote a series of essays on the nature of the hipster and what constitutes hipster culture, if there is such a thing. We overwhelmingly concluded that there is no unified hipster culture, that they produce no unique or identifiable cultural artifacts, and this is one of the primary reasons for their failure—or, since perhaps they weren’t trying in the first place—to form a distinct movement of any kind. I’ve heard arguments along the same lines applied to emo: that there is no identifiable emo music, literature, or art; that emo kids themselves disagree on what aesthetics define emo; that “real” emo was over long before the word/concept ever really took off, and so nothing after maybe 1998 (the year is highly debatable) counts as emo; etc. I have no better working definition of emo than the next emo kid, but I will argue that—unlike hipsters, though the difference between the two is not especially what I mean to emphasize—there are coherent ideas and thought processes running through the whole of the emo movement/scene/what have you, that the lifestyle or, really, epistemology, emerged in the wake of punk rock and still persists in some form. I do not pretend that the authenticity and quality of what is popularly considered emo music has maintained the high standard it once had (you can laugh here), and the degradation and hence bad reputation emo music has endured is in no small part due to the inevitable effects of commercialization. The point I mean to make is one about shared experience: whether your canonical emo band is Sunny Day Real Estate, or Brand New, or Bright Eyes, or Dashboard Confessional, etc., your general worldview has a great deal in common with that of another emo kid from a different time or place, etc. along the emo continuum.

The condition of the emo kid is easy to write off as unfettered vanity and self-indulgence, the case for this view being that emo kids are, in the main, relatively privileged and unaffected by what most people consider to be real traumas of contemporary life, ie, they are situated (usually) well above the poverty line, and have never been exposed to or threatened with extreme violence. We find it hard to sympathize with adolescents and young adults who have grown up sheltered at a time when millions of children have real problems. And, during my own stint as a self-described emo kid, the guilt I felt around feeling dissatisfied with my life (guilt from the knowledge that others had it way worse and yet I found so much about which to complain, or, more accurately, to almost deliberately make myself miserable) was a significant part of the system of malaise I wove in my head.

That said, it’s as hard to convincingly argue that emo kids do have at least a few actual problems, and that these problems are the common threads between different versions or incarnations of emo. And I’ll concede that, even in hindsight, I can’t say that they even were real problems, but it sure as fuck felt like it: the certainty and gravity of the conclusions I drew about myself and other people trumped any remaining capacity I had for objectivity. Everyone really was unendurably vapid and insensitive, and I really was going to maintain my destructive habits unto lifelong loneliness. That’s how it seemed. Part of ceasing to be emo—rather, as emo—was my growing need to apologize for how absurd I sounded in pretty much every communicative act I made, how absurdly I behaved for several solid years. The other part was discovering better art, better music, and most importantly better literature, and realizing that there were far more comprehensive and sustainable ways to deal with the world than the thought processes I mired myself in. And, as has become apparent in this essay, I still continually apologize for emo—to anyone who has been emo, and to anyone who has had any sort of relationship with an emo kid.

With the apology must come the explanation of what it is I am apologizing for. The epistemology of emo, I have decided centers around the following emotional ideology: The emo kid sees in herself some pattern of self-destructive behavior and finds herself both unable to stop and unwilling to continue, but because she is unable to stop, she must continually question whether or not she really is unwilling to continue, and if she is not, she must question what intrinsic flaw makes her weak-minded or truly self-destructive or both. The self-destructive behavior might be a desire for romantic relationships characterized by severe dependence and/or “trust issues,” a desire for meaningless sexual encounters, eating disorders, cutting, repeated alienation of friends, drug and alcohol problems of a fairly minor order, etc. Her ability to question whether or not she wants to stop in the first place leads her to conclude that she is not truly, hopelessly addicted to anything, and indeed she usually is not, but draws her conclusion from an assumption that truly, hopelessly addicted people have already lost the ability to question want vs. need vs. un- or subconscious drive. But, at the same time, the fact that she continues whatever destructive behavior she likely knows she has chosen leads her to further question why she hasn’t totally destroyed herself—ie. she is not dead, or incarcerated, or in rehab, or pregnant. She has never reached and maybe never been close to total destruction, and she sees this as evidence that she is still in control of her actions, and therefore fully capable of “fixing” herself without outside help. Her ultimate self-analysis, and this usually takes at least a year to arrive at, is that she enjoys being somewhat—but, obviously, not entirely—self-destructive, enjoys the level to which she can predict what causes her pain. There’s no real way to tally how many emo kids slowly pulled themselves out of the emo condition vs. how many did go to rehab or join a religious organization or otherwise make some drastic life change that shocked them out of their particular self-destructive behavior more or less overnight. And I am fairly certain that members of the latter category are harsher critics of emo, and those most willing to argue that the emo mentality has no redeeming qualities for anyone. I don’t blame them. I only want to describe, as clearly as possible, the strategies common in every emo kid’s approach to thought and life in general. I call the totality of my conclusions the epistemology of emo because the emo movement, for all its fragmentation, describes a condition of the individual that is all-encompassing. The reason, I think, why former emo kids are so easy to spot, and why they tend to stick together, is that the whole tempest of skewed logic leaves its etchings on the walls of the mind. It’s why someone ten years older than me uses the same word to describe incredibly different artistic periods: ever since punk rock gave us permission to question our role and agency as adolescents, and grunge gave us permission to rage inwardly at whatever we happen to hate about ourselves, emo kids have been inventing and perfecting the cultural artifacts that feed the attitude and vice versa.

Her pieces have appeared in Correspondence 1 & 2, and more of her work is available at maesaslaw.wordpress.com.

Some months ago, The Correspondence Society and friends wrote a series of essays on the nature of the hipster and what constitutes hipster culture, if there is such a thing. We overwhelmingly concluded that there is no unified hipster culture, that they produce no unique or identifiable cultural artifacts, and this is one of the primary reasons for their failure—or, since perhaps they weren’t trying in the first place—to form a distinct movement of any kind. I’ve heard arguments along the same lines applied to emo: that there is no identifiable emo music, literature, or art; that emo kids themselves disagree on what aesthetics define emo; that “real” emo was over long before the word/concept ever really took off, and so nothing after maybe 1998 (the year is highly debatable) counts as emo; etc. I have no better working definition of emo than the next emo kid, but I will argue that—unlike hipsters, though the difference between the two is not especially what I mean to emphasize—there are coherent ideas and thought processes running through the whole of the emo movement/scene/what have you, that the lifestyle or, really, epistemology, emerged in the wake of punk rock and still persists in some form. I do not pretend that the authenticity and quality of what is popularly considered emo music has maintained the high standard it once had (you can laugh here), and the degradation and hence bad reputation emo music has endured is in no small part due to the inevitable effects of commercialization. The point I mean to make is one about shared experience: whether your canonical emo band is Sunny Day Real Estate, or Brand New, or Bright Eyes, or Dashboard Confessional, etc., your general worldview has a great deal in common with that of another emo kid from a different time or place, etc. along the emo continuum.

The condition of the emo kid is easy to write off as unfettered vanity and self-indulgence, the case for this view being that emo kids are, in the main, relatively privileged and unaffected by what most people consider to be real traumas of contemporary life, ie, they are situated (usually) well above the poverty line, and have never been exposed to or threatened with extreme violence. We find it hard to sympathize with adolescents and young adults who have grown up sheltered at a time when millions of children have real problems. And, during my own stint as a self-described emo kid, the guilt I felt around feeling dissatisfied with my life (guilt from the knowledge that others had it way worse and yet I found so much about which to complain, or, more accurately, to almost deliberately make myself miserable) was a significant part of the system of malaise I wove in my head.

That said, it’s as hard to convincingly argue that emo kids do have at least a few actual problems, and that these problems are the common threads between different versions or incarnations of emo. And I’ll concede that, even in hindsight, I can’t say that they even were real problems, but it sure as fuck felt like it: the certainty and gravity of the conclusions I drew about myself and other people trumped any remaining capacity I had for objectivity. Everyone really was unendurably vapid and insensitive, and I really was going to maintain my destructive habits unto lifelong loneliness. That’s how it seemed. Part of ceasing to be emo—rather, as emo—was my growing need to apologize for how absurd I sounded in pretty much every communicative act I made, how absurdly I behaved for several solid years. The other part was discovering better art, better music, and most importantly better literature, and realizing that there were far more comprehensive and sustainable ways to deal with the world than the thought processes I mired myself in. And, as has become apparent in this essay, I still continually apologize for emo—to anyone who has been emo, and to anyone who has had any sort of relationship with an emo kid.

With the apology must come the explanation of what it is I am apologizing for. The epistemology of emo, I have decided centers around the following emotional ideology: The emo kid sees in herself some pattern of self-destructive behavior and finds herself both unable to stop and unwilling to continue, but because she is unable to stop, she must continually question whether or not she really is unwilling to continue, and if she is not, she must question what intrinsic flaw makes her weak-minded or truly self-destructive or both. The self-destructive behavior might be a desire for romantic relationships characterized by severe dependence and/or “trust issues,” a desire for meaningless sexual encounters, eating disorders, cutting, repeated alienation of friends, drug and alcohol problems of a fairly minor order, etc. Her ability to question whether or not she wants to stop in the first place leads her to conclude that she is not truly, hopelessly addicted to anything, and indeed she usually is not, but draws her conclusion from an assumption that truly, hopelessly addicted people have already lost the ability to question want vs. need vs. un- or subconscious drive. But, at the same time, the fact that she continues whatever destructive behavior she likely knows she has chosen leads her to further question why she hasn’t totally destroyed herself—ie. she is not dead, or incarcerated, or in rehab, or pregnant. She has never reached and maybe never been close to total destruction, and she sees this as evidence that she is still in control of her actions, and therefore fully capable of “fixing” herself without outside help. Her ultimate self-analysis, and this usually takes at least a year to arrive at, is that she enjoys being somewhat—but, obviously, not entirely—self-destructive, enjoys the level to which she can predict what causes her pain. There’s no real way to tally how many emo kids slowly pulled themselves out of the emo condition vs. how many did go to rehab or join a religious organization or otherwise make some drastic life change that shocked them out of their particular self-destructive behavior more or less overnight. And I am fairly certain that members of the latter category are harsher critics of emo, and those most willing to argue that the emo mentality has no redeeming qualities for anyone. I don’t blame them. I only want to describe, as clearly as possible, the strategies common in every emo kid’s approach to thought and life in general. I call the totality of my conclusions the epistemology of emo because the emo movement, for all its fragmentation, describes a condition of the individual that is all-encompassing. The reason, I think, why former emo kids are so easy to spot, and why they tend to stick together, is that the whole tempest of skewed logic leaves its etchings on the walls of the mind. It’s why someone ten years older than me uses the same word to describe incredibly different artistic periods: ever since punk rock gave us permission to question our role and agency as adolescents, and grunge gave us permission to rage inwardly at whatever we happen to hate about ourselves, emo kids have been inventing and perfecting the cultural artifacts that feed the attitude and vice versa.

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

No Wave

What Is Not Post-Feminism?

Some Questions and Problems

by Lonely Christopher

Feminism is a problem of the discursive relationship between theory and praxis. Feminism is simultaneously an academic/theoretical grammar and a sociopolitically applicable ideology. There’s much confusion about what being a feminist means right now; the concept oft languishes as an empty signifier mouthed weirdly by women stuck between third wave and post-feminist perspectives --- those of no wave. Where does the deconstruction of essentialisms become the eschewing or even denial of an affirmative and required praxis of and for contemporary women? Feminism: is institutionalized (theory divorced from praxis in academia), becomes a museum piece (in Brooklyn, where the feminist wing of the museum was founded a year or so back), gets erased by poststructural pluralism, (and/or) just sounds dirty because it can’t cohere as a system sufficiently balancing the pragmatic and existential. What does it mean for a male to identify as feminist or to write about feminism (the latter happening here)? How much room has been made for minority perspectives or is the problem of petit-bourgeois feminism, of a possible feminist hegemony, a bad framing device? Has second wave activism been too eschewed or is it poststructural subjectivities that have been overly ignored? Does a multiplicity of feminisms strengthen feminist thought/praxis conceptually or obliterate all efficacies? How much feminist discourse is today still articulated using the vocabulary of the second wave and does that make such discourse outmoded? bell hooks, decades ago: “Feminism is a struggle to end sexist oppression.” Where does Butler’s subsequent gender confusion and performative play fit in an oppositional/corrective conception of praxis-based feminism? Where fits art and thought designed to critique and explore rather than directly promote change? What is feminism without the concept of change, without being synonymous with the transformative influence of praxis? Is continued social change resulting in the promotion of women “more feminist” than Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” or isn’t the distinction between activism and art so clear? If, according to the “post” model, feminism is no longer relevant as a contemporary rubric, what now? There probably isn’t more feminism after post-feminism. The problem with post-feminism, its failure, is that is not so contemporary as premature. As a theoretical and socially inapplicable model, post-feminism reads okay as a subset of another post-positioned idiom (postmodernism?), but maybe it negatively closes discourses that should stay available so as to acknowledge the work remaining for change-oriented praxis. Perhaps it’s similar to pushing a post-gay perspective in a sociopolitical context of widespread inequality and subjugation (today, still). When somebody playfully says, “You’re here, you’re queer, get over it!” one wants to tersely respond, “You get over it!” The argument against oppression is declared falsely efficacious, allowing the problem to go on underhandedly. Is this the case with feminism? to what extent? These problems, arising decades ago and remaining unresolved, are some qualities of the no wave that troubles the idea of feminism as a coherent logic. Is this really all just about power or, if not, what else (and how much else)? Christine Wertheim recently writes: “The Subject of History may be dead, but all of the […] others⎯the women, blacks, the queer, and the poor⎯in whom power never resided, still don’t have their share of discursive space.” When does anti-essentialism end up privileging the sneaky normative that refuses being argued out of domination of power relations and ideological discourse? This is nothing more than a recital of problems and questions; unknown is how many questions are rhetorical and how many pertinent but unanswerable. The only likely conclusion in this context is that what and how feminism is represent problems to be addressed, positively, as points of centrifugal departure.

Some Questions and Problems

by Lonely Christopher

Feminism is a problem of the discursive relationship between theory and praxis. Feminism is simultaneously an academic/theoretical grammar and a sociopolitically applicable ideology. There’s much confusion about what being a feminist means right now; the concept oft languishes as an empty signifier mouthed weirdly by women stuck between third wave and post-feminist perspectives --- those of no wave. Where does the deconstruction of essentialisms become the eschewing or even denial of an affirmative and required praxis of and for contemporary women? Feminism: is institutionalized (theory divorced from praxis in academia), becomes a museum piece (in Brooklyn, where the feminist wing of the museum was founded a year or so back), gets erased by poststructural pluralism, (and/or) just sounds dirty because it can’t cohere as a system sufficiently balancing the pragmatic and existential. What does it mean for a male to identify as feminist or to write about feminism (the latter happening here)? How much room has been made for minority perspectives or is the problem of petit-bourgeois feminism, of a possible feminist hegemony, a bad framing device? Has second wave activism been too eschewed or is it poststructural subjectivities that have been overly ignored? Does a multiplicity of feminisms strengthen feminist thought/praxis conceptually or obliterate all efficacies? How much feminist discourse is today still articulated using the vocabulary of the second wave and does that make such discourse outmoded? bell hooks, decades ago: “Feminism is a struggle to end sexist oppression.” Where does Butler’s subsequent gender confusion and performative play fit in an oppositional/corrective conception of praxis-based feminism? Where fits art and thought designed to critique and explore rather than directly promote change? What is feminism without the concept of change, without being synonymous with the transformative influence of praxis? Is continued social change resulting in the promotion of women “more feminist” than Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” or isn’t the distinction between activism and art so clear? If, according to the “post” model, feminism is no longer relevant as a contemporary rubric, what now? There probably isn’t more feminism after post-feminism. The problem with post-feminism, its failure, is that is not so contemporary as premature. As a theoretical and socially inapplicable model, post-feminism reads okay as a subset of another post-positioned idiom (postmodernism?), but maybe it negatively closes discourses that should stay available so as to acknowledge the work remaining for change-oriented praxis. Perhaps it’s similar to pushing a post-gay perspective in a sociopolitical context of widespread inequality and subjugation (today, still). When somebody playfully says, “You’re here, you’re queer, get over it!” one wants to tersely respond, “You get over it!” The argument against oppression is declared falsely efficacious, allowing the problem to go on underhandedly. Is this the case with feminism? to what extent? These problems, arising decades ago and remaining unresolved, are some qualities of the no wave that troubles the idea of feminism as a coherent logic. Is this really all just about power or, if not, what else (and how much else)? Christine Wertheim recently writes: “The Subject of History may be dead, but all of the […] others⎯the women, blacks, the queer, and the poor⎯in whom power never resided, still don’t have their share of discursive space.” When does anti-essentialism end up privileging the sneaky normative that refuses being argued out of domination of power relations and ideological discourse? This is nothing more than a recital of problems and questions; unknown is how many questions are rhetorical and how many pertinent but unanswerable. The only likely conclusion in this context is that what and how feminism is represent problems to be addressed, positively, as points of centrifugal departure.

Sunday, September 20, 2009

This Is Going To Be Fun

Here is an announcement about an exciting event coming soon to Brooklyn’s Unnameable Books (one of the city’s best literature merchants, which, incidentally, stocks all three titles of the Corresponding Society’s “No Know” chapbook series, fyi):

Gay Play 3

a new play by Lonely Christopher

presented in a dramatic reading at Unnameable Books

25 September, that is Friday, 8pm, free and one night only!

600 Vanderbilt (at St Marks), Brooklyn

This is going to be fun. Lonely Christopher presents a dramatic reading of the third installment in his internationally produced Gay Play trilogy. Gay Play 3 is something like a closet opera about queer history, shortly before Stonewall, made into a soupy meal using leftovers of Beckett, “The Boys in the Band,” a textbook on structuralism, and Greek tragedy. One day it will be staged entirely in an inflatable pool. Each entry in the trilogy is a standalone piece; familiarity with the previous installments is not required for enjoyment. Gay Play 1 was first staged last summer at the Bowery Poetry Club, Gay Play 2 premiered in dual Mandarin/English productions this August in ChengDu, China, and this event marks the first ever presentation of Gay Play 3.

a dramatic reading featuring:

Jake Abrams

Taylor Derwin

Sam Kline

& Lonely Christopher

Gay Play 3

a new play by Lonely Christopher

presented in a dramatic reading at Unnameable Books

25 September, that is Friday, 8pm, free and one night only!

600 Vanderbilt (at St Marks), Brooklyn

This is going to be fun. Lonely Christopher presents a dramatic reading of the third installment in his internationally produced Gay Play trilogy. Gay Play 3 is something like a closet opera about queer history, shortly before Stonewall, made into a soupy meal using leftovers of Beckett, “The Boys in the Band,” a textbook on structuralism, and Greek tragedy. One day it will be staged entirely in an inflatable pool. Each entry in the trilogy is a standalone piece; familiarity with the previous installments is not required for enjoyment. Gay Play 1 was first staged last summer at the Bowery Poetry Club, Gay Play 2 premiered in dual Mandarin/English productions this August in ChengDu, China, and this event marks the first ever presentation of Gay Play 3.

a dramatic reading featuring:

Jake Abrams

Taylor Derwin

Sam Kline

& Lonely Christopher

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Saturday, September 12, 2009

A year without David Foster Wallace, a summer with Infinite Jest

Mae Saslaw is this month's guest editor. Her pieces have appeared in Correspondence 1 & 2, and more of her work is available at maesaslaw.wordpress.com. Her next post will be considerably more organized than what follows, and may contain a cogent argument. In the mean time, she will abuse this forum for reasons unapparent.

One year ago tonight, Lonely Christopher called me up to say that David Foster Wallace had committed suicide. I did what any friend would do and started to feed Lonely Christopher alcohol. About twenty minutes after he arrived, he got a call from Greg, whose appendix was near bursting. It was a weird night. But that’s not what this post is about.

I was one of the people who hadn’t actually read any of Wallace’s work—outside of an essay or two for class—prior to his death. I’ve spent the last twelve months catching up, and to date I’ve read Oblivion, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, Girl with Curious Hair, and most recently, Infinite Jest. I started Infinite Jest intending to follow along with the Infinite Summer people and go to their meetings on Thursdays in the Village. That didn’t happen, but I did finish the book. What was extraordinary was the amount of attention I got just for carrying the thing around. One girl approached me on a subway platform and asked if I’d read an essay of Wallace’s that had appeared in the New Yorker at some point, because if I hadn’t, she was going to give me her copy.

Ordinarily, I have a pretty limited amount of patience for the general public and carry an admittedly larger-than-justifiable sense of superiority when it comes to my tastes in fiction. Example: I once saw a boy my age reading Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser on a subway car filled with screaming preteens. I wanted to lean over and tell him, “Don’t even try reading that book now; you won’t understand a damn thing.” I ultimately didn’t say anything, but only because I didn’t want him to think I was coming onto him. I am an asshole. To be fair, I also had the reverse happen to me: Last summer, when I was trying to read Gravity’s Rainbow, a heavily-tattooed gentleman (carrying a copy of The Confessions of St Augustine) interrupted me and asked, first of all, if I could possibly read on a sweltering train with headphones on, and second, if I was trying to read the book without a companion volume. I said something like, “I’m reading it for the sentences,” and then bitched about the heat and how I wanted a cigarette. I must have come off looking pretty fucking cool. That’s not what this post is about, either.

I have a hard time being direct about this, about what reading Infinite Jest this particular summer and finishing up last week was really like. I guess it was something like this: