Hipster Week at The Corresponding Society Internet Presence belatedly continues, sort of. Several members of The Corresponding Society have been asked to evaluate contemporary hipster culture for the purpose of better understanding the social phenomenon we are exposed to daily.

On Why There Is No Definition of a Hipster

by Mae Saslaw

There is no static criteria for determining hipsterdom and therefore no established method for distinguishing a hipster. For this reason, an individual's hipster status may be entirely up for debate or interpretation, questionable, or at least shaky. It is easy enough to imagine a hipster denying hipster status⎯and this is common behavior⎯but is it possible to be a non-hipster and self-identify as one? If so much of one's hipster status rests upon one's identification or lack thereof as a hipster, and yet there are no rules governing who is or is not same, is anyone actually a hipster? More importantly, is anyone entering into a discourse regarding hipster status not a hipster? This is the fluid nature of hipsterdom. But why are there no criteria, why is there no litmus test? In any other counter-culture or sub-culture movement of the past thirty years, there have been concrete characteristics of members of the group. For example, the punk movement was clearly marked by dress, music, lifestyle, etc. This has served in the past as a unifying, solidifying necessity for any group: members want to establish their membership and broadcast it in a legible way. Hipsters have avoided hipster solidarity, and I propose two linked reasons: 1) they hate each other because 2) "hipster" has been a pejorative term since its inception. Hipsters typically complain about a lack of authenticity exhibited by other hipsters, and these complaints are misplaced due to a certain phenomenon my peers have described, namely, there is no such thing as an authentic hipster. How does such a "movement" founded on absolutely nothing occur, let alone persist? Given that identifying hipsters is such a slippery slope to begin with, I propose that the very existence of hipsters may be purely linguistic. One can refute or deny his or her hipsterdom, providing evidence such as dress and places of habitation or social activity, but the question will usually remain unanswered. By contrast, punk identity is significantly easier to define, if only because the punk movement produced its own culture. Hipsters produce notions of hipsterdom, but no cultural artifacts to help establish a movement. It is counterintuitive to imagine that mere notions can form identity, and yet they have. Is it not these very notions that are being discussed, and are they not substantive enough to warrant their own discussion? Despite the fact that the word "hipster" exists and has been accepted in common usage, it is barely legible; it reminds me of that historic Supreme Court opinion on pornography: I can't define it, but I know it when I see it.

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

The Hipster Function

It’s Hipster Week at The Corresponding Society Internet Presence. Several members of The Corresponding Society have been asked to evaluate contemporary hipster culture for the purpose of better understanding the social phenomenon we are exposed to daily.

The Hipster Function

by Lonely Christopher

Hipster culture is remarkable because so few of its adherents self-identify as hipsters. The contemporary hipster is not interested in a unified movement, he is not interested in politics, he is not even that interested in individuality. The hipster is a ghost. Hipster culture has already happened and is being rearticulated as a trace; it is a collage of past styles, trends, names. The hipster does not make important contributions to the arts. The hipster has no god. This complicit relationship with cultural colonization and this erasure of being are certainly not sustainable, but sustainability probably isn’t contemporary. In reaction to generations of youth movements with countercultural stances that have been muted by failure and appropriation the hipster affects a sense of ennui and disinterest in counterculture or opposition. Situationism failed, the contemporary hipster won’t even try. It’s not valid to read the hipster as a disgraced countercultural figure; the hipster isn’t part of a counterculture, not even a subculture, but maybe the first metaculture. Hipster culture takes place on the plane of hegemonic culture, not outside it or in a niche. The Internet is integral to the hipster because it eschews centrality, even presence. The preferred accessory of the hipster is a camera, but with it he does not create art; he distances himself from being through representation. This is a striving for a mechanical sameness, a continual series of images that homogenize subjects and reinterprets the individual as a cultural function. The most graspable aspect of the hipster is his uniform: the meticulous hair, the skinny pants, the glasses, the studied irony omnipresent in the fashion. Yet, unlike the symbolic dress of more political youth cultures, it doesn’t signify anything, usually not even the evident assumption that the wearer of the uniform self-identifies as a hipster. The presentation doesn’t cohere into meaning, but neither does it offer resistance to a codifying repetitiousness that taxonomically references the ambiguous vacancy of the idea of the hipster. The hipster is absence. Maybe it’s a valid reaction to contemporary existence resulting from social adaptation. Yet the hipster function is tragic in its inability to create art. The creative expressions within hipster culture articulate the same implicit surrender to vapidity that is evidenced in hipster values; the work is nearly worthless in the context of a wider artistic discourse and, thereby, defenseless. Whereas a contemporary movement in poetics like Conceptual Writing renegotiates meaning in intellectually engaging ways, hipster art can only be self-referential in the manner it relentlessly perpetuates the same placeless, lackadaisical cultural performance. The hipster is surely an important contemporary figure, but what is significant about him is ineffable; it’s about what and how the hipster doesn’t mean.

The Hipster Function

by Lonely Christopher

Hipster culture is remarkable because so few of its adherents self-identify as hipsters. The contemporary hipster is not interested in a unified movement, he is not interested in politics, he is not even that interested in individuality. The hipster is a ghost. Hipster culture has already happened and is being rearticulated as a trace; it is a collage of past styles, trends, names. The hipster does not make important contributions to the arts. The hipster has no god. This complicit relationship with cultural colonization and this erasure of being are certainly not sustainable, but sustainability probably isn’t contemporary. In reaction to generations of youth movements with countercultural stances that have been muted by failure and appropriation the hipster affects a sense of ennui and disinterest in counterculture or opposition. Situationism failed, the contemporary hipster won’t even try. It’s not valid to read the hipster as a disgraced countercultural figure; the hipster isn’t part of a counterculture, not even a subculture, but maybe the first metaculture. Hipster culture takes place on the plane of hegemonic culture, not outside it or in a niche. The Internet is integral to the hipster because it eschews centrality, even presence. The preferred accessory of the hipster is a camera, but with it he does not create art; he distances himself from being through representation. This is a striving for a mechanical sameness, a continual series of images that homogenize subjects and reinterprets the individual as a cultural function. The most graspable aspect of the hipster is his uniform: the meticulous hair, the skinny pants, the glasses, the studied irony omnipresent in the fashion. Yet, unlike the symbolic dress of more political youth cultures, it doesn’t signify anything, usually not even the evident assumption that the wearer of the uniform self-identifies as a hipster. The presentation doesn’t cohere into meaning, but neither does it offer resistance to a codifying repetitiousness that taxonomically references the ambiguous vacancy of the idea of the hipster. The hipster is absence. Maybe it’s a valid reaction to contemporary existence resulting from social adaptation. Yet the hipster function is tragic in its inability to create art. The creative expressions within hipster culture articulate the same implicit surrender to vapidity that is evidenced in hipster values; the work is nearly worthless in the context of a wider artistic discourse and, thereby, defenseless. Whereas a contemporary movement in poetics like Conceptual Writing renegotiates meaning in intellectually engaging ways, hipster art can only be self-referential in the manner it relentlessly perpetuates the same placeless, lackadaisical cultural performance. The hipster is surely an important contemporary figure, but what is significant about him is ineffable; it’s about what and how the hipster doesn’t mean.

Monday, August 11, 2008

The Hipster in Context

It’s Hipster Week at The Corresponding Society Internet Presence. Several members of The Corresponding Society have been asked to evaluate contemporary hipster culture for the purpose of better understanding the social phenomenon we are exposed to daily. This project may be read as a response to writerly communities developing simultaneously with but separate from ours that embrace values associated with contemporary hipster culture, though the focus is often broader.

The Hipster in Context

by Greg Afinogenov

All previous countercultures since you could really begin to speak of a counterculture⎯I would say, since the Romantics⎯have been fundamentally grounded in an appeal to authenticity. The Romantics prided themselves on their ability to express pure emotion. The Symbolists⎯Rimbaud most of all⎯constantly sought the link to Being, the limit-experiences that break through the surface of daily life. The Surrealists attempted to realize art by using the unconscious (maybe the ultimate appeal to authenticity). The Beats followed the Symbolists, sometimes. The hippies, of course, were a paradigm case: the return to Rousseau, the emphasis on the purity of agriculture. (You could say that the New Left, too, was searching for authenticity in a kind of Frantz Fanonian revolutionary self-realization.) The punks ditched society's rules, exposing its shallowness by bringing forth an animalistic brutality; “Evolution is a process too slow to save my soul,” sang Darby Crash. And what is hip-hop but a constant return to the true and real life of the streets from the obfuscation of the white man's tricknology? (Listen to Brand Nubian for the way this process interacts with Nation of Islam imagery.)

A relatively new trend in Western thought⎯and culture⎯changed this familiar pattern, even before the hipsters. The idea of authenticity, after Derrida (after Nietzsche), became a dirty word. Authenticity was exposed as an ideological abstraction, an unachievable origin point that generates an endless chain of "supplements" which bring us farther and farther away from it. There was no more defending the concept of unmediated experience.

Hipsterdom is the first counterculture to arise with and take into account the condition that we, for better or worse, call “postmodernity.” As such, it cannot appeal to authenticity; it plays with surface, with collage, with costume⎯with everything “superficial.” But of course this could never be innocent while capitalism was around to sell it everything it needed. Thus hipsterdom stopped being a “counter” culture on any substantive level at all: there has almost never been a group of non-mainstream youth so invested in the preservation of the system, for all their Naomi Klein platitudes.

Hipster self-hatred is the return of the repressed appeal to authenticity. After all, hipsterdom incorporated into itself all of its predecessors. The self-hatred, then, is the condemnation of everything it stands for by the value systems it inherited⎯which provide the only semblance of a normative content hipsterdom can ever manifest. This means hipsterdom is constantly at odds with itself, unable to resolve the contradiction between its countercultural heritage and its thoroughly capitalized rejection of authenticity. Authenticity, within hipsterdom, is a zombie⎯dead, yet unkillable, and always threatening.

This contradiction lies behind the most familiar elements of hipster culture. Pabst, high-school sports T-shirts (until recently?), Bruce Springsteen, old vinyl, trucker hats⎯all these are the paraphernalia of a world where authenticity could be easily and unproblematically assumed, the earnest and unpretentious vanished world of the blue-collar male. Of course, this is ironic: in searching for authenticity hipsterdom once more encounters only its superficial, external expressions. (This was Derrida's point, in a way. The hipsters are looking for authenticity, “presence,” but can only seem to reach it by constructing a “supplement,” which seems like a pretty good facsimile of the real thing until you realize that it never resolves the aporia, the gap between the authentic and the fake, which made it necessary to begin with.)

Is there a future for the counterculture as a social formation? I don't think so. The hipsters mark the point where rebels stop selling out and start buying in.

The Hipster in Context

by Greg Afinogenov

All previous countercultures since you could really begin to speak of a counterculture⎯I would say, since the Romantics⎯have been fundamentally grounded in an appeal to authenticity. The Romantics prided themselves on their ability to express pure emotion. The Symbolists⎯Rimbaud most of all⎯constantly sought the link to Being, the limit-experiences that break through the surface of daily life. The Surrealists attempted to realize art by using the unconscious (maybe the ultimate appeal to authenticity). The Beats followed the Symbolists, sometimes. The hippies, of course, were a paradigm case: the return to Rousseau, the emphasis on the purity of agriculture. (You could say that the New Left, too, was searching for authenticity in a kind of Frantz Fanonian revolutionary self-realization.) The punks ditched society's rules, exposing its shallowness by bringing forth an animalistic brutality; “Evolution is a process too slow to save my soul,” sang Darby Crash. And what is hip-hop but a constant return to the true and real life of the streets from the obfuscation of the white man's tricknology? (Listen to Brand Nubian for the way this process interacts with Nation of Islam imagery.)

A relatively new trend in Western thought⎯and culture⎯changed this familiar pattern, even before the hipsters. The idea of authenticity, after Derrida (after Nietzsche), became a dirty word. Authenticity was exposed as an ideological abstraction, an unachievable origin point that generates an endless chain of "supplements" which bring us farther and farther away from it. There was no more defending the concept of unmediated experience.

Hipsterdom is the first counterculture to arise with and take into account the condition that we, for better or worse, call “postmodernity.” As such, it cannot appeal to authenticity; it plays with surface, with collage, with costume⎯with everything “superficial.” But of course this could never be innocent while capitalism was around to sell it everything it needed. Thus hipsterdom stopped being a “counter” culture on any substantive level at all: there has almost never been a group of non-mainstream youth so invested in the preservation of the system, for all their Naomi Klein platitudes.

Hipster self-hatred is the return of the repressed appeal to authenticity. After all, hipsterdom incorporated into itself all of its predecessors. The self-hatred, then, is the condemnation of everything it stands for by the value systems it inherited⎯which provide the only semblance of a normative content hipsterdom can ever manifest. This means hipsterdom is constantly at odds with itself, unable to resolve the contradiction between its countercultural heritage and its thoroughly capitalized rejection of authenticity. Authenticity, within hipsterdom, is a zombie⎯dead, yet unkillable, and always threatening.

This contradiction lies behind the most familiar elements of hipster culture. Pabst, high-school sports T-shirts (until recently?), Bruce Springsteen, old vinyl, trucker hats⎯all these are the paraphernalia of a world where authenticity could be easily and unproblematically assumed, the earnest and unpretentious vanished world of the blue-collar male. Of course, this is ironic: in searching for authenticity hipsterdom once more encounters only its superficial, external expressions. (This was Derrida's point, in a way. The hipsters are looking for authenticity, “presence,” but can only seem to reach it by constructing a “supplement,” which seems like a pretty good facsimile of the real thing until you realize that it never resolves the aporia, the gap between the authentic and the fake, which made it necessary to begin with.)

Is there a future for the counterculture as a social formation? I don't think so. The hipsters mark the point where rebels stop selling out and start buying in.

Thursday, August 7, 2008

Vaguely Pertinent/Miscellaneous/Unrelated

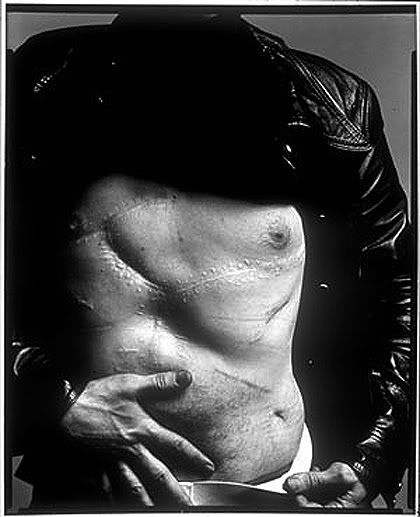

Richard Avedon’s portrait of Warhol imposes a particular/directed reading

And: Unprompted promotional charity on the Internet, self-demeaning jocularity, promise of one lucky winner, praise for a particular play, events punching beings, an Appalachian whorehouse, Shakespeare’s contemporariness, lyrical rhizomatic explosions, postcard biographies, the critical treatment of the life of Andy Warhol, a sculpture made out of information in the shape of its subject, the centrality of absence, an anecdote about identity...

1. The Corresponding Society is giving away a copy of the first issue of Correspondence for fun. This is called promotion, I guess, I’m not sure. To qualify, all someone has to do is read this very entry we have posted on our Internet blog (I pray that qualifies at least one lucky so-and-so) and be the first to send us an email informing us that she is the winner (whereupon we will happily mail out her spoils gratis [though in the more likely event that she is somebody we know and see on a daily basis, who has just avoided spending money on a copy, we’ll just deliver it personally]). We wish every one of the many devotees of this Internet presence the best of luck in this matter.

2. The Corresponding Society urgently implores all residents of New York City to make reservations to see the play Twelve Ophelias, written by Caridad Svich and presented by the Woodshed Collective. It’s playing through August, with free admission, at Williamsburg’s delightful McCarren Pool. The production has systematically astonished just about every available member of The Corresponding Society recently. I saw it first knowing nothing about it⎯it’s just one of those things, those serendipitous events that punch your being unexpectedly. Quite loosely, the conceit involves Ophelia resurfacing to find herself in an alternate existence where Elsinore is a whorehouse in Appalachia and Hamlet is a backwoods miscreant called the Rude Boy. No other recent production predicated upon Hamlet has proven how alive Shakespeare’s play still is, how important, how adaptable. As a writer who has been closely studying Hamlet for over a year, it was an indescribable experience watching the play I love and know so well breathing inside and through a new body. Hamlet is ours, Hamlet is depthless, and this interpretation lyrically explodes Hamlet rhizomatically. Also, it’s a musical.

3. Michael Kimball, author of the new novel Dear Everybody, is also a prolific biographer who writes the life stories of strangers on the backs of individual postcards; recently he profiled the poet Lonely Christopher (though forwent mentioning the subject’s status as web editor of The Corresponding Society) on his blog. To segue awkwardly into the more appropriate use of first person when referring to myself, I was intrigued to participate in this project. When my postcard biography arrived in the mail my reaction was decidedly mercurial, but as a dedicated reader of books on the lives of others I have come to understand and accept that biography is an art of interpretation: a writer doesn’t explicate the life of his subject, he performs it. I recently read two biographies of Andy Warhol, one by Victor Bockris and the other by Wayne Koestenbaum. The former, thicker and more grounded, posed as an objective account of a life but implicitly failed to avoid shaping the Warholian data into a writerly narrative necessitating judgment, a sculpture made out of information and opinion shaped like its subject. The latter was far more flamboyant about its distance from a definitive conception of Warhol; Koestenbaum knew he couldn’t reconstruct his subject in facsimile⎯so he took the available data and thoughtfully used it to build a structure around the absence. When I read my own abbreviated biography I saw Kimball performed a reduction of the accumulation of source data, like a sculptor addressing a block of marble (or maybe a preexisting, larger, and more detailed marble statue), to narrow and redefine my self-narrative into his narrative of my self as his subject. The extremely compact nature of this project is illustrated by how, ultimately, my biography is reduced to a list of drastic labels perhaps meant to suggest taxonomy (ergo I am summarized with words that imply concision yet are calculated to corroborate the stance of the whole piece). While some of what he posits upsets me or strikes me as a misreading (“As a form of self-medication, he started drinking as a high school freshman.”), there is at least one imposition of causal narrative that I found illuminating (“In kindergarten [he] couldn’t tell the difference between writing and drawing, which still influences his approach to writing.”). To put it differently, allow me to retell (rewrite, perhaps, or write) an anecdote from Bockris’ treatment of Warhol without having the text available for reference. Warhol lived with his mother Julia Warhola in New York City; perhaps he mistreated her, perhaps she was taken to drink. Maybe there was an argument and Julia’s resultant departure from the house, whereupon she returned to Pittsburg where she had raised Andy and his brothers. Consequently, Andy’s household might have fallen into neglect (presumably because Andy was helpless without his mom). Julia was probably convinced to come back by those concerned with her son’s welfare, and she did come back, but when she did she stormed into the apartment, threw her suitcase angrily down, and, in front of her son and most likely some of his close friends, declared of herself, “I’m Andy Warhol!”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)